17. Southeast Asia's Unique Aesthetic

(Although located in Travelogues SEA2 Chap folder, this article is part of SEA Empires. These 7 chapters, 10>16, belong between SEA5:Ch8a & SEA6:Ch09. This particular article is excerpted from SEA Travelogues SEA3:Ch15 & SEA3:Ch17.)

- Buddhist monks vs. Hindu god-kings

- Theravada vs. Hindu art

- Similarities in Southeast Asian Art

- The Naga in Art

- The Southeast Asian Mindset

Due to Mongol invasions, the Thai people migrated from their kingdom in southern China and eventually supplanted the Khmer as the dominant political power on the Southeast Asian mainland. The KhmerŌĆÖs artistic tradition was based upon a blend of Hinduism and Mahayana. Influenced by Burma, the ThaiŌĆÖs artistic tradition was primarily rooted in Theravada Buddhism. In other words, Theravada influenced the art and hence temples of the western part of Southeast AsiaŌĆÖs mainland, while Hinduism/Mahayana was the primary influence upon the Khmer temples. LetŌĆÖs compare and contrast the differences in the 2 traditions.

Buddhist monks vs. Hindu god-kings

In many ways, Mahayana Buddhism is more compatible with Hinduism than it is with Theravada. Mahayana and Hinduism are associated with king worship; both believe in reincarnation; and both tolerate the worship of multiple gods. Theravada believes in neither king worship, nor reincarnation. While somewhat tolerant of other deities, the Buddha is always the main one. Hence when we refer to Buddhism in this discussion, we are referring to Theravada, and when we refer to Hinduism we are referring to Mahayana as well, especially as manifested at Angkor.

Theravada Buddhism is based on transcendent merit. Monks sustain this religious standard. They have no interest in kings - except as a patron. While the monks might take great interest in the world of spirits and local traditions, these are subordinated to the higher truths of Buddhism. Buddhist monasteries are built around stupas or pagodas - which are domed monuments emblematic of greater truth. These Buddhist complexes include preaching halls, living quarters and libraries. As an example, the stupa is the primary type of temple shrine found in Chiang Mai, a world center of Theravada, located in Northern Thailand. The temple complex always included the stupa, the living quarters of the monks, a library, and the preaching hall where monks are frequently seen giving lectures to the people.

The Theravada King was not identified as a divine Bodhisattva, as he was in the Mahayana tradition. However, provision was made in legend, ritual, monastic and court tradition for the ruler of a Theravada country to assume a more marginal role as a patron. Although Theravada Buddhism had no place for a divine ruler, they relied on the local king for support. This support included funding stupas in ever increasing size and number, which were continually enlarged and rebuilt. Further the KingŌĆÖs icon was prominent in scenes from the BuddhaŌĆÖs life. He was frequently shown as a principle disciple or as Prince Siddhartha before he became Buddha. Simplistically speaking, the Hindu king can be a god or Bodhisattva, while the Theravada king is spiritually subservient to the Buddhist monks.

The current Thai king in the 21st century is of this nature. He is in charge of tending to the construction, maintenance, and the refurbishing of the myriad stupas in the country. While he is not quite considered a god or Buddha by the Thai people, he is certainly treated as the main political servant of Buddhism.

Theravada vs. Hindu art

Theravada and Hindu art also manifest quite differently. Theravada tends to be fundamentalist. Their artists and writers are encouraged to stay as close as possible to the original art and literature of their Buddhist tradition. They believe that if the originals are not copied precisely then they are not effective - no transcendent function. It is similar to the idea that a recipe must be followed exactly to get the best taste. Because of this idea much Buddhist art is formulaic.

This orientation to exact imitation led to a relative monotony of style in their icons of the Buddha. He has some 50 postures that are meant to be duplicated as closely as possible because they are intended to remind the viewer of a specific lesson. In subsidiary sculpture and painted figures they are allowed greater freedom of invention, but creativity of representation for their primary figures is discouraged, as it takes away from the message.

While the Thai representations of the Buddha are quite constant, they vary the externals of their temples tremendously. Some writers have even described these surfaces as ŌĆśgaudy with gilt paint and colored glassŌĆÖ. This is an exaggeration. Most experience the temples with awe and amazement. Rather than overdone or excessive, the Thai style is reminiscent of elaborate Baroque ornamentation. The many mirrors reflect the sun. The reflected sunlight dissolves the massiveness of the structure, generating a sense of transcendence.

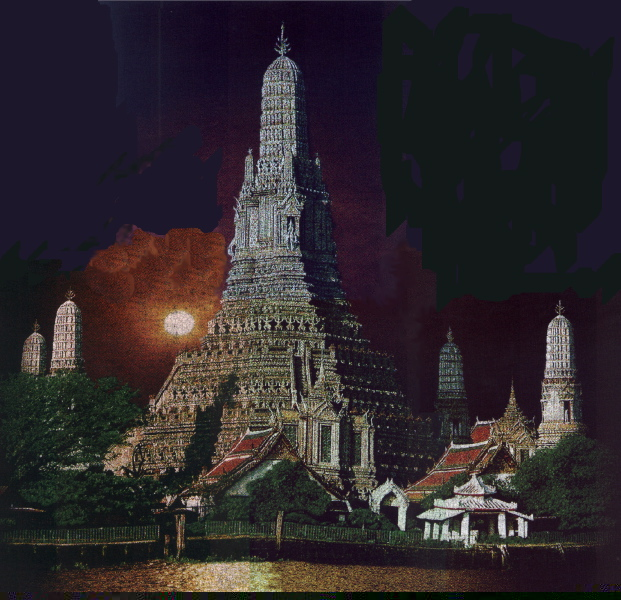

In contrast to this rigid idea of message in Theravada, the Hindu and Mahayana schools recognized aesthetic values as a component of religious expression. Hence their artists were encouraged to express themselves creatively - channeling the divine in a variety of ways. In Bangkok's Temple of the Dawn devoted to the Hindu god Shiva, the experience of the art itself inspires the viewer to transcend the verbal duality to attain union with Being.

Similarities in Southeast Asian Art

While we create artificial intellectual boundaries to differentiate the temples, there are many congruencies in Southeast Asian art. Both Hindu and Buddhist art are derived from the magical and animistic art of the shaman turned priest. The people of Southeast Asia tend to believe that spirits respond to the power of art, whether it be aesthetic as in Hinduism or conceptual as in Buddhism.

As contrasted with the word-based cultures of the Chinese or the Jews, the art and temples of the Khmer and Thai cultures are incredibly visual. While the predominant themes at Angkor had to do religious and national history, the representations are so artistic that anyone could appreciate them regardless of background. Understanding the doctrine was not essential to experiencing the awe.

In both Hinduism and Buddhism, the life and personality of Buddha and the Hindu gods became fused with native figures - just like in Catholicism. The Demons or Yakshas of these Eastern religions became merged with the evil spirits of the local cultures. Birds of Indian mythology merged with the indigenous sacred symbols such as the sun, peacock and eagle. The Lion, while unknown in the monsoon rain forest, became a popular motif borrowed from Hinduism and Buddhism. Singapore, city of the Lion, with its Merlion logo, is a good example of this borrowing.

The Naga in Art

The Naga serpent, a popular Indian symbol, also merged with local counterparts. In Burma, the Buddha is frequently shown with a snake-crested head. In Burmese and Mon representations the Buddha sits upon a coiled Naga body with the snakeŌĆÖs head as an umbrella. This iconography is derived from representations of Vishnu and is meant to suggest their equivalence. In this regard, the Hindus believe that Buddha is one of Vishnu's many incarnations. The Mon shows the Naga as a crocodile, who could only swim, while the Khmer and Indonesians portray the Naga as 9-headed snake, who could also fly. Stone Nagas frequently guarded palaces and temples. Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom are good examples of this. While Buddhism frowned upon Naga worship, the Naga was regularly shown as a servant of Buddha, guarding him from attack. The Thais, heir to the symbols of the Khmer and the Mon, regularly used the Naga to guard their Buddhist stupas. The Naga serpent guards the Buddha images throughout Chiang Mai, not so much in syncretic Bangkok.

The primitive fertility worship of the Naga/snake dragon was retained in the Khmer Empire. The 9-headed Naga was used as a symbol of fertility and royalty. Remember that the original Khmer kingdom of Funan traced their ancestry to Soma, who was a Naga princess. This use of the Naga in conjunction with Hinduism and Buddhism by the Khmer and the Thai represents the assimilation of the energy of the indigenous culture with the Indian culture ŌĆō the balance of yin and yang. This is contrasted with the vilification of the serpent in the Biblical West and the corresponding separation and hostility between the artistic and the political - between the sacred and the mundane. Southeast Asians love snakes, their Nagas. They live in harmony with them - rather than in fear and opposition.

Southeast Asian Mindset

This syncretic attitude is also reflected in Southeast AsiaŌĆÖs unique aesthetic. While Southeast Asian artists have been influenced by and thereby have an affinity with IndiaŌĆÖs art, they only used it as a stepping stone, rather than slavishly copying it.

While China has always been an important mercantile influence, their artistic influence has been minimal on the Southeast Asian mainland. Burma, although an important trade route to China, shows no artistic affinity with them. The Thai, while next-door neighbors to the Chinese for thousands of years, shed Chinese art forms for those of the Khmer and Mon, after they migrated to the Southeast Asian mainland. The exception is their temple roofs and lacquer work. A Chinese province for a 1000 years, Vietnam is another exception.

The difference between the Chinese and Indian influence is illustrated in the difference between the temple tombs of the Khmer and the emperor tombs of Vietnam. The Khmer king loses his human personality as he merges with the otherworldly Hindu divinities and is surrounded by aesthetic and graceful statuary from mythology. In contrast, the Chinese emperor is shown in an opulent setting - surrounded by his worldly possessions - in very formal and dignified poses. His social status is stressed rather than de-emphasized.

Although Islam has exerted an enormous religious and political influence on the Southeast Asian populace over the last six hundred years, the artistic influence is minimal - no artistic affinity. To express the reality beneath the false beauty of the external world, the Muslims reject animal and human forms, which the Southeast Asian artists are so fond of.

Although India exerted a huge cultural influence on the population, India's religions, Hinduism and Buddhism, taught that the sensual world was false and transitory. This attitude found no place in the Southeast Asian heart. The cultures and art of the area mixed reality and fantasy so completely that it is impossible to differentiate one from the other.

The Khmer and Javanese temples were meant to suggest that heaven is on earth - not in the afterlife, as Christians or Muslims teach - or in rebirth, as the Hindus teach - or in enlightenment, as the Buddhists teach - or in a great nation, as the Jews teach. Instead their art communicates a joyous acceptance of life. The Khmer and the Javanese merged the life of the gods with the life of the people. They simultaneously express the joyous, the earthy, and the divine. They have no crucifixes with a suffering Jesus.

In Southeast Asia, there is no division between secular and religious art. Tattoos are the same as temple adornments or a lacquer tray. Because of this lack of separation, there is no echo of the European concept of ŌĆśart for arts sakeŌĆÖ. They use no models, for they have no need to be anatomically correct. They are not obsessed with photographic realism because they are not obsessed with literal reality. The intrusion of fantasy and the joyousness of life make Southeast Asian art forms unique on this planet.

Again the merger of all aspects of life manifests in their language, which contain ŌĆśexpressivesŌĆÖ. This unique feature of Southeast Asian languages epitomizes their culture. This type of word suggests synesthetic experiences, which reflect both their religion, which is syncretic, and their lives, which blend beauty, religion, art, music, food, drama in one package. Southeast Asians donŌĆÖt tend to separate everything into isolated compartments.

In a similar vein, Southeast Asian society also rejected the extreme caste system of India and the hierarchy of China. The scenes of chariots and domination on their temple walls confused historians because they implied a typical Bronze Age society with a dominant oligarchy. Furthering the confusion was the use of hierarchical words of Sanskrit to describe an individualŌĆÖs position in the society. However, each member of their society is important. They have no untouchables. Even the people of the Hill Tribes are considered part of the community. Everyone belongs. No one is excluded. Everyone has an honorable position.

Southeast Asian cultures have embraced the arts and crafts since their beginnings. The first evidence of their high level of craftsmanship comes from the prehistoric bronze making culture circa 3000 BCE. The quality of their artwork has remained high ever since. However, the subject matter has shifted.

Indian culture exerted a significant influence on their art in the Common Era, especially their literature. Not only did their religious novels influence the builders of the Angkor temple complex, these stories also motivated temple builders from Burma in the west, to Vietnam in the east, to the island cultures of Java in the south. Check out the next chapter for a beginning introduction to the Ramayana, one of IndiaŌĆÖs most influential books.