Nei-yeh (Chinese Self-Cultivation Manual)

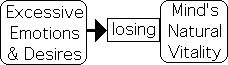

3. Emotions & Desires disrupt Mind’s natural Vitality.

1 All the forms of the mind (hsin)

2 Are naturally infused and filled with it [vital essence/jing],

3 Are naturally generated and developed [because of] it.

4 It is lost

5 Inevitably because of sorrow, joy, happiness, anger, desire, & profit-seeking.

6 If you are able to cast off sorrow, joy, happiness, anger, desire, & profit-seeking,

7 Your mind will just revert to equanimity.

8 The true condition of the mind

9 Is that it finds calmness beneficial and, by it, attains repose.

10 Do not disturb it, do not disrupt it,

11 And harmony will naturally develop.

Commentary

Verse 3 focuses upon hsin, another key concept in Chinese thought, past and present. Hsin is most commonly translated as ‘heart-mind’.

Lines 1-4:

1 All the forms of the mind (hsin)

2 Are naturally infused and filled with it [vital essence/jing],

3 Are naturally generated and developed [because of] it.

4 It is lost

The first four lines have some inherent ambiguity associated with them due to the word ‘it’. What does the word ‘it’ refer to?

Roth, our translator, assumes that ‘it’ refers to ‘vital essence/jing’, as indicated by his brackets. When we substitute jing for ‘it’, the lines become ‘mind’s forms are infused with jing, the source of vitality. Jing is lost when …’ Roth’s reading is certainly plausible in terms of the context of later verses and traditional associations.

The hazard of relying on standard interpretations is that they have the potential to limit our cognitive horizons. As mentioned in the introductory chapter, the Nei-yeh employs many of Taoism’s traditional concepts in a manner that differs from other Taoist classics, for instance the Tao Te Ching. As such, we are proposing the wisdom of an approach that resists traditional Taoist associations until the Nei-yeh makes the connections for us. The customary mindset could very well prevent us from discovering additional perspectives that might actually broaden our understanding.

Roth’s suggestion that ‘it’ refers to jing is certainly a plausible translation. Although jing is a significant element in Verse 1 as well as in later verses, the current verse does not actually include the ideogram for jing. Instead, it focuses primarily on the innate nature of hsin. Rather than superimposing jing on Verse 3, our approach suggests that we focus our interpretation upon the actual ideograms employed in the text.

An examination of the ideograms of the first 4 lines of Verse 3 suggests to us another insightful translation. These lines employ a parallel construction that uses the ideogram for ‘natural’ on four occasions.

Roth’s interpretation argues that the mind is an object that is infused, filled, generated and developed, and all because of jing. Roth’s translation connotes that the mind is a thing that can be filled with jing. Since the word jing does not appear in the text, another interpretation may be useful.

The mind can also be characterized by what it does – its fundamental activities or processes. The lines tell us that the mind is engaged in 4 types of ongoing activities. The word ‘natural’ is used to modify each of these processes: infusing, filling, generating, and developing. Due to this pattern, it is quite likely that the ‘it’ in line 4 could refer to these natural processes of the mind, rather than to jing as Roth suggests.

4 It [these natural processes of the mind] is lost when …

I think it is fair to say that these 4 natural processes are associated with the state of mental and emotional vitality. To avoid excess verbiage, we will employ the word ‘vitality’ as a general term for all 4 processes. Abbreviating for clarity, the mind (hsin) is naturally filled with vitality (shêng).

![]()

Lines 4-5:

4 It [mind’s natural vitality] is lost

5 Inevitably because of sorrow, joy, happiness, anger, desire, and profit-seeking.

Subsequent lines describe the mind’s fall from this original purity. Hsin, our heart-mind, loses its natural perfection due to emotions and desires, both positive and negative, e.g. ‘sorrow, joy, happiness, anger and desire’. Are these lines suggesting that all emotions and desires undermine our natural state?

Even though the verse does not say as much, it seems reasonable to assume that these lines are referring to excessive emotions and desires. For instance, not all forms of joy or anger would be considered excessive, but there are other types that surely would be considered unbalanced. This assumption is certainly consistent with traditional Chinese thought, which typically stresses finding the balance point between extremes. Rarely does Chinese philosophy suggest the outright denial of emotions and desires.

Another culprit that undermines mind’s original purity is ‘profit-seeking’, the last character of lines 5 & 6. Are these lines suggesting that all profit-seeking disrupts the mind? Or could it just be referring to excessive greed? The ideogram can also be translated as ‘taking advantage of others’, motivated perhaps by the craving for power or wealth. Advancing one’s position at the expense of others is the excessive attachment to profit-seeking that is disruptive of mind’s natural vitality.

Lines 6-9:

6 If you are able to cast off sorrow, joy, happiness, anger, desire, & profit-seeking,

7 Your mind will just revert to equanimity.

8 The true condition of the mind

9 Is that it finds calmness beneficial and, by it, attains repose.

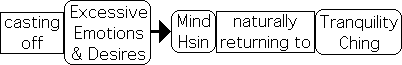

Casting off these excessive emotions and desires results in hsin, our heart-mind, ‘naturally’ returning to a state of ‘repose’. Tranquility (ching) is an incredibly important word-concept in the Nei-yeh that appears to be used as a synonym for ‘repose’. For this reason, we’ve chosen to employ the word ‘tranquility’ rather than ‘repose’ in the following diagram.

Lines 10-11:

10 Do not disturb it, do not disrupt it,

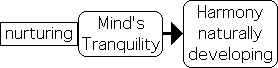

11 And harmony will naturally develop.

These lines counsel us to refrain from disturbing or disrupting mental tranquility. In other words, after achieving a ‘state of repose’, we must nurture it. Abiding in this tranquil state naturally results in developing harmony.

Again the emphasis is on a process that develops harmony, i.e. equilibrium. After recognizing the dangers of excessive emotional states such as extreme ‘anger’ or even extreme ‘happiness’, we must be vigilant to prevent them from resurfacing. In this manner, we learn to develop what can be viewed as the habit of tranquility, ultimately becoming harmony.

What’s the difference between tranquility and harmony? Although the definitions seem similar, the text suggests that tranquility is a component of harmony. Tranquility could be a momentary state. The Nei-yeh appears to clearly suggest that intentionally sustaining tranquility results in the more enduring state of harmony. This sustainable state of equilibrium is a key asset that could be carried into the rest of our lives.

The Nei-yeh regularly employs the meta-theme of “attaining and then sustaining”. Attaining an elevated state is important yet not enough; we must also sustain it to achieve the full benefits. We saw this same developmental process in the last verse regarding ch’i. After welcoming ch’i, we must hold onto it in order to achieve a deeper understanding.

An implicit assumption, supported in other verses, is that we can’t directly pursue harmony. Instead we must engage in an indirect 2-step approach. ‘Casting off’ excessive emotions and desires is the first step in this process. Nurturing the resulting tranquility is the second step. If we can adhere to this straightforward 2-step process, harmony will naturally develop.

The Nei-yeh’s 26 verses frequently counsel us to utilize an indirect approach. Recall from the last verse that we can’t directly summon ch’i by commands or by force. Instead we must be attract ch’i indirectly by both welcoming and nurturing it.

‘Acting Naturally’ vs. Guiding Natural Developmental States

‘Natural’ is a key word in the Nei-yeh. An underlying assumption seems to be that mind’s ‘natural’ state is good but is corrupted by disruptive emotions. If we can but cast off excessive emotions and cravings, we ‘naturally’ return to mind’s original state of harmony and vitality. But what does ‘natural’ mean in this context?

Some readers might misinterpret ‘natural state’ to mean ‘acting naturally’ – effortlessly following our immediate inclinations. However, a closer reading of the text suggests a very different interpretation. An implicit feature of this verse is that mind’s ‘natural state’ of vitality is only achieved by acts of the will. We must intend to both restrain our extreme impulses and to cultivate ‘calmness’ or ‘repose’. In other words, regaining and maintaining the mental tranquility that is the root of vitality and harmony requires cognitive effort. Could this be achieved by exercising the te-yi synergy, i.e. self-restraint and guidance?

The Nei-yeh is quite clear about the negative consequences of effortlessly following our ‘natural’ inclinations, rather than exerting intentionality. Failing to restrain and guide, not eliminate, our internal urges frequently leads to the excesses that drives away hsin’s natural perfection. In other words, ‘going with the flow’, rather than guiding it, usually results in emotional turbulence, rather than the mental tranquility that results in vitality.

Reiterating for retention: hsin’s ‘natural’ state is good in that it consists of harmony and vitality. However our ‘natural’ inclinations are bad in that they frequently result in excessive emotions and desires, which disrupt this harmony. Rather than allowing these natural inclinations to run their destructive course, we must guide (yi) and restrain (te) hsin’s behavioral momentum. Mental effort is required to return to hsin’s natural perfection. The necessity of exerting mental energy to guide our thoughts and behavior rather than following our natural inclinations is also seen regularly through the Nei-yeh.

An unspoken question from this verse: How do we rid ourselves of the excessive emotions and cravings that upset the ‘natural’ vitality of hsin, our heart-mind?

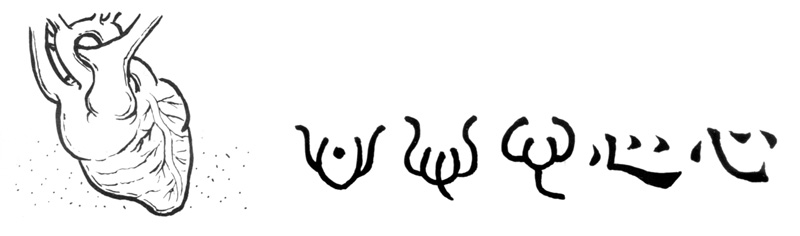

Hsin: the Ideogram

Although hsin is frequently translated as ‘mind’, it is associated with our heart, rather than our brain. In order to provide the proper connotations, a traditional translation of hsin is ‘heart-mind’. Below is the ideogram for hsin.

The ideogram developed from a rough rendition of the lobes of the biological heart.

While the pictogram derived from a static thing – a material heart, hsin represents a dynamic process. Most of the Nei-yeh’s most significant word-concepts are also processes, rather than things. Due to its connection to the processes of the heart-mind, hsin is associated with both our emotions and our thoughts. Under this schema, our emotions and thoughts compose an intertwined, perhaps inseparable, network. Further our emotional mind goes through an infinite number of transformations - changing nearly instantly from one feeling to another, sometimes due to a mere smile or frown.

As an indication of its importance, this ideogram appears as a component of countless ideograms.

Hsin, the heart-mind: Brain/Emotion Synergy

Recall from Verse 1 that Sages have jing (life force) at the core of their being. Zhöng, our core, is associated with our biological heart rather than our brain. Note that we want jing to reside, not in what we call our central nervous system, but rather in the core of our circulatory system.

Biologically the heart, not the brain, is essential for life. It is possible for the brain to be dead and the organism to remain living. When our heart stops beating, we die. In such a way, the heart is connected to being, rather than thinking.

Associated with the biological heart, hsin is most frequently translated as heart-mind. As such, we want jing to reside in hsin, our heart-mind, rather than our brain. As we shall see, jing is not the only cosmic energy that we want to attract to this central location. According to the Nei-yeh, we want to create internal conditions that will attract all the cosmic energies to the same spot – the core of our body – the heart – the essence of being.

The heart is associated with emotions in China as well as in the West. In the first few decades of the 21st century, cognitive scientists have come to a consensus that cognition and affect, i.e. heart and mind, form a gestalt – a separable yet fully integrated system. In other words, emotions are an integral part of our thought process. The notion of hsin encompasses this understanding.

Could it be that we want to attract the cosmic energies to hsin, our core, in order to channel the cognitive-emotional energy that drives our lives?

Summary

Verse 3: Hsin, our heart mind, is naturally filled with the processes of infusing, filling, generating, and developing, which we have abbreviated as vitality. Emotions disrupt this natural perfection. If disruptive emotions are eliminated, hsin naturally returns to perfection.

The initial verses introduce many unanswered questions. How do we get jing in the center of our chest and become Sage-like? What does it mean to ‘develop te’? And how do we eliminate the disruptive emotions that upset hsin’s natural perfection? As an indication of the Nei-yeh’s developmental nature, the ensuing verses address these questions.