Nei-yeh (Chinese Self-Cultivation Manual)

5. Tranquil Mind & Regular Ch'i Flow to attain the Tao

1 The Way (Tao) has no fixed position;

2 It resides in the excellent mind (hsin).

3 When the mind is tranquil and the vital energy (ch’i) is regular,

4 The Way can thereby be halted.

5 That Way is not distant from us;

6 When people attain it they are sustained.

7 That Way is not separated from us;

8 When people accord with it they are harmonious.

9 Therefore: Concentrated! as if you could be roped together with it.

10 Indiscernible! as beyond all locations.

11 The true state of the Way:

12 How could it be conceived of and pronounced upon?

13 Cultivate your mind, make your thoughts tranquil,

14 And the Way can thereby be attained.

Commentary

Verse 5 articulates some additional features of the Tao: its advantages, where it resides, and how to keep it there.

Lines 1-2:

1 The Way (Tao) has no fixed position;

2 It resides in the excellent mind (hsin).

The verse begins by reiterating that the Tao does not have a set location. Although not fixed, the Tao resides in an excellent heart-mind (hsin). Hsin can be viewed as the cognitive processes, perhaps even neural networks, that produce our personal behavior patterns. How do achieve an excellent hsin so that the Tao will abide?

![]()

Lines 3-4:

3 When the mind (hsin) is tranquil and the vital energy (ch’i) is regular,

4 The Way can thereby be halted.

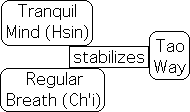

Recall from the prior verse that the Tao is elusive – coming and going somewhat unpredictably. However, a tranquil mind and regular ch’i halts, i.e. stabilizes, the Tao.

These lines can be interpreted in a variety of ways. There are two conditions that stabilize the Tao. The first is a tranquil hsin, i.e. a heart-mind that is undisturbed by disruptive emotions and desires (from Verse 3) and thoughts (yi) as we see emphasized in this verse. A tranquil mind is seemingly a component of the excellent mind that attracts the Tao. This condition is relatively unambiguous.

The second condition has more possibilities. Ch’i is associated with breathing and blood flow, i.e. oxygenation of the body. To stabilize the Tao, our ch’i must be regular. ‘Regular ch’i’ could certainly refer to regulating our breathing.

It could also refer to the energetic flow of ch’i throughout our body’s channels. One of the main functions of Tai Chi practice is to open up the body’s energetic channels to allow our ch’i to flow naturally to all parts of the body. This regular ch’i flow is enlivening – increasing personal vitality. We can imagine that this type of regular ch’i flow could certainly be a factor that would stabilize the Tao.

Further, the movements should be even, i.e. ‘regular’. In Tai Chi, one of Master Ni’s main principles is unceasing continuous motion. Interruptions and/or abrupt movements waste precious energy. There are many types of physical exercise, e.g. bicycling, jogging and walking, that serve the same function, i.e. regulating the breath and increased blood flow.

It seems that a tranquil mind and good ch’i flow stabilize the Tao within us. Why is this important?

Lines 5-8:

5 That Way is not distant from us;

6 When people attain it they are sustained.

7 That Way is not separated from us;

8 When people accord with it they are harmonious.

9 Therefore: Concentrated! as if you could be roped together with it.

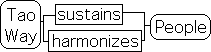

The Tao, i.e. the Way, has at least two clearly distinguished referents. The distinction is between specific practices, skills, or methods – carving an ox, surfing or cultivation practices such as meditation or taiji, and the laws of nature or the cosmos, the unseen, all-pervading, inconceivable whole. Conventionally in English translation, the former is written with a lower case ‘t’, a tao. The latter is indicated with an upper case T – the Tao.

Here are some classic examples that highlight the two usages. The first line in Lao-tzu could be translated, “the tao that can be spoken/followed is not the constant Tao.” As Chuang-tzu makes clear in the anecdote of the butcher, a tao, any tao, practiced with attention and consistency can lead to spatial-temporal instances of alignment with the one and only Tao. Line 13 in this verse, as we shall see, suggests some tao-s, though not named as such, for alignment with the Tao.

Lines 5 and 7 refer to the cosmic Tao, the natural rhythms of existence. This passage evokes the wave metaphor. The Tao is available to those who are ready to catch its wave – presumably those with a calm mind and good ch’i flow. A major feature of catching the Tao’s wave is timing. Waiting for the proper time is huge. Tapping into the Tao’s natural rhythms is both sustaining and harmonizing.

As an optimum method, the tao could represent the ideal self-cultivation practices that lead to the ability to tap into the Tao, the rhythms of nature. These practices are not distant in that they can be performed any time that one has the proper intent. Regular practice sustains and harmonizes those who follow this Path. This understanding of the Tao does not necessarily imply a transcendent mystical experience.

Due to these positive benefits, the Nei-yeh counsels us to bind ourselves to the Tao as if with a rope. This binding suggestion applies to the Tao as either self-cultivation practices or natural rhythms. Attuning to the Tao requires diligence and single-minded focus from either perspective.

Lines 10-14:

10 Indiscernible! as beyond all locations.

11 The true state of the Way:

12 How could it be conceived of and pronounced upon?

13 Cultivate your mind; make your thoughts tranquil,

14 And the Way can thereby be attained.

This passage reiterates the ineffable nature of the Tao. Its true state has no location. Could this mean that no definition will contain the Tao?

Line 12 employs a rhetorical question to imply that we should avoid thinking or speaking about the ‘true state’ of the Tao. Why? Could this be because the ineffable Tao is similar to incomprehensible energy, which we only know from results? Due to this innate incomprehensibility, thinking about the Tao’s essence is a waste of mental energy. If thinking or speaking about the Tao is ineffectual, how do we attract and stabilize the Tao?

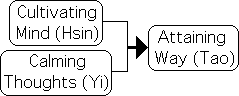

While conceptualizing it is impossible, the verse finishes by stating that ‘cultivating our heart-mind (hsin)’ and ‘calming our thoughts (yi)’ result in ‘attaining the Tao’. If calm thoughts connect us with the Tao, then agitated thoughts drive away the Tao. It seems that excessive emotions and desires (from Verse 3) and agitated thoughts (from this verse) disrupt the mental tranquility that attracts the Tao.

Yi: the Mentation Complex

Both lines 12 and 13 contain the ideogram for yi. Recall from Verse 2 that yi can mean ‘will’, ‘intent’ or ‘intentionality’. Here it appears with a different, though related, meaning. The initial definitions derive from the root meaning of yi: ‘thoughts, thinking or conceptualization’. Due to context, Roth translates yi in the root sense as ’conceive of’ or simply ‘thoughts’, i.e. thinking.

These two lines are quite specific about the relationship between the Tao and yi (thinking). Rather than actively thinking (yi) about the true state of the Tao, we should instead focus upon calming our thoughts (yi). Again the Nei-yeh suggests an indirect approach to attracting and stabilizing the Tao within our core.

By what mechanism do we calm our thoughts? We can easily imagine that the te/yi synergy operates in a complementary fashion to achieve inner tranquility. Te is employed to restrain ‘thoughts/thinking’ from drifting in an unproductive direction, i.e. ‘attempting to understand the true nature of the Tao’. Yi as intent is employed to direct our attention in a more productive direction, i.e. towards calming our thoughts (yi) and regulating our breath (ch’i).

Understood from this perspective, yi is simultaneously attention, will, and thoughts. To gain control of our thoughts (yi), we employ our will (yi) to direct our attention (yi) towards tranquility. In a later verse, yi is associated with our non-verbal thoughts – pre-verbal mentation. As a gestalt, yi could be conceptualized as a preverbal thinking complex that includes thoughts, will and awareness in one package.

This yi complex can go feral if not restrained. Like children, the mentation synergy tends to spiral out of control without proper guidance. Left to their own devices, our innate or learned cognitive processes might multiple example upon example of perceived injustices. These inflaming examples provide the ideational fuel that sustains negative or arousing emotions. Instead of allowing this negative process to achieve any momentum, especially bio-chemical, we employ yi to curb, shape and guide our thoughts towards tranquility. With each repetition of this process, the probability of negative behavior decreases and vice versa. This is the process of cultivating hsin (the heart-mind).

I Ching: Applying will to thoughts, like applying discipline in a Family

The I Ching refines our understanding of runaway thoughts. The hexagram for Family consists of the Fire Trigram at the base and the Wind Trigram on top. The third line from the bottom is a Yang line. Due to its position, i.e. the top of the Fire Trigram, this yang line represents applying discipline to harmonize the family.

When this yang line is imbalanced, i.e. reaches its limit, the I Ching provides an ancient song-poem that is applicable.

“If the Family is run with ruthless severity, tempers flare up.

Remorse is the consequence.

Good Fortune nonetheless.

If women and children are too frivolous,

Humiliation is the consequence.”

Paraphrasing: Although too much discipline results in ‘remorse’, this is better than too much leniency, which results in ‘humiliation’.

The I Ching’s verbiage has distinctly patriarchal overtones. If the patriarch of the clan does not exert enough discipline, then women and children will engage in frivolous behavior that leads to humiliation. The implicit message: To avoid embarrassment for the family, the father must be strict.

Liu I-Ming, an 18th century follower of Taoism’s Inner Alchemy, provides a more egalitarian message to this passage from the I Ching. He likens the process to self-cultivation. In his commentary, the family consists of our many selves, i.e. the variety of components that comprise our psyche. We might rebel against the strict discipline, perhaps a tight regimen that we impose upon our selves, especially our thoughts. Better too strict than too lenient with our inclinations.

“Otherwise, there are thoughts that do not leave and one becomes lazy and tricky, indulging in feelings and desires. How can one reach selflessness? Those who practice in this way never attain the Tao; they only get humiliation. This indicates the need for firmness in refining the self.”1

In similar fashion, we must apply the te/ye synergy – restraint and direction, else our thoughts will become too ‘frivolous’, i.e. indulgent. Indulging our thoughts and feelings leads to ‘humiliation’, i.e. biochemical feedback that disrupts our tranquility. This imbalanced psycho-physiological state erodes cognitive skills and physical vitality. Better to err on the side of too much discipline than not enough.

In this particular verse, the Nei-yeh counsels us to both calm our thoughts and refrain from fruitless speculation on the Tao. If we are too lenient, the te/yi synergy atrophies due to lack of use. With no cognitive strength to guide and restrain our thoughts, runaway emotions disturb our mental tranquility, which repels the Tao. Conversely if we employ yi/will to guide our thoughts towards quietude, this attracts the Tao.

Journey to the West: Making the Will Tranquil

Lines 13 and 14 could be interpreted yet another way. Instead of ‘thoughts’, yi could be translated as ‘will’. “Cultivate the heart-mind (hsin) by making the will (yi) tranquil to attain the Tao.” What does it mean to make the ‘will’ tranquil?

Journey to the West, the celebrated Chinese allegorical novel, provides us with an example. Tripitaka, a Buddhist monk, travels West to India to obtain holy scriptures from the Buddha. A horse carries him on this mystic Quest. The Horse represents the Will (yi), and is frequently referred to as such. In this context, Tripitaka could be said to represent hsin, the heart-mind.

Whenever the Horse of the Will gets spooked, Tripitaka gets thrown off and the Quest is threatened. Before proceeding, the Horse must be calmed down. Why does the Horse run too fast? Sometimes the Horse is frightened and other times Tripitaka is too excited to reach his destiny. The symbolism is fairly straightforward. The will (yi) can become too excited either from fear or enthusiasm. In either case, the excess of will prevents Tripitaka from reaching the Buddha – attaining the Tao. In order to achieve our goals, we must calm our ‘will’ from imagined fear or over-enthusiasm. Rather than getting ahead of ourselves or becoming overwhelmed by negative emotions, the solution is to focus our ‘will’ on the task at hand.

It is amazing how just a few lines can be interpreted in so many ways.

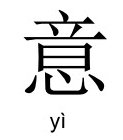

Yi: the Ideogram

As seen, the word-concept yi is a significant word-concept in the Nei-yeh. We’ve examined its verbal components, i.e. definitions and contextual meanings in terms of the individual verses. Let us gain a visual understanding of the term by examining yi’s ideogram.

Sometimes ideograms evolve. Other times they are consciously constructed. As examples, intentionality, as well as evolution, provided the modern ideograms for yin, yang, ch’i, and Sage. Let us proceed under the assumption that conscious intent played a part in the construction of yi’s ideogram. Put more precisely, we are going to disregard scholarly veracity and instead freely project personal meaning onto the interaction between the 3 symbols that comprise yi’s ideogram.

At the top of yi’s ideogram is the symbol for li, which means ‘to stand upright’. In the middle is the sun symbol2. At the bottom is the symbol for hsin (heart-mind).

As yet another indication of the complementary nature of te and yi, the ideograms for the two word-concepts have a parallel construction in the sense that they both include hsin, the heart-mind symbol, at their base. This signifies that they fall into a semantic group of terms that concern cognition in some form or another. In the Nei-yeh's context, the three word-concepts are definitely linked. Te (self-restraint) and yi (intention) are the mental tools with which hsin (the heart-mind) is cultivated.

The sun’s central location in the pictogram is reminiscent of the aptly named solar plexus. Rather than the verbal brain, the power of will emanates from the center of the body. In similar fashion, Don Juan, the Yaqui Indian sorcerer/warrior in the Carlos Castaneda series, also issued power from his stomach. In both instances, gut instinct or intuitions are at the base of will rather than words and ideas. Later verses of the Nei-yeh also emphasize the importance of yi’s non-verbal component.

The symbolic interaction between the 3 components of yi’s pictogram also yields profound meaning. The ideogram for li, the symbol at the top, derived from the pictogram of a man standing planted upon the ground. 3 His legs are spread apart in a position of authority – someone who is in control of himself and his world4.

The aligned body at the top, with the sun in the middle and the heart-mind at the base is suggestive of standing meditation from Tai Chi, also the tree pose from Yoga, or rooting from the martial arts. While standing, we attempt to clear our mind of verbal thoughts and focus upon body alignment. In fact, we deliberately redirect our consciousness from our brain to our lower tan tien, the psychic center just below our navel, the surmised location of the sun symbol. This intentional (yi) process both enhances ch’i flow and calms our thoughts. As this verse reports, both of these processes are features of the excellent hsin in which the Tao abides.

Summary

Verse 5: The Tao abides in an excellent hsin (heart-mind). It sustains and harmonizes those with an excellent hsin. Hsin is excellent when it is tranquil (ching) and ch’i flow is regular. Don’t waste mental energy by thinking and talking about the unknowable Tao. Instead cultivating hsin and making our thoughts tranquil results in attaining the Tao. Following these self-cultivation practices, the Tao, rather than being transient, will abide within our center (zhöng).

Footnote

1 Taoist I Ching, Liu I Ming, translated by Thomas Cleary, Shambala Publications, 1986, p. 144

2 Weiger, p.311, Lesson 143A. Weiger's book was first published in 1915, over a century ago. Chinese scholarship has come a long way since then. While much of his analysis is outdated, it is still suggestive of meaning. In using him as source, we are deliberately sacrificing scholarly accuracy for personal meaning.

3 Weiger, p.157, Lesson 60H

4Chinese Calligraphy, Edoardo Fazzioli, Rebecca Hon Ko, p.68