Nei-yeh (Chinese Self-Cultivation Manual)

8. ‘Guiding Ch’i’ results in Vitality; Excess Knowledge harms Vitality.

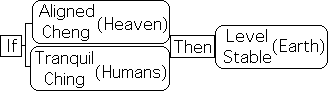

1 If you can be aligned and be tranquil,

2 Only then can you be stable.

3 With a stable mind (hsin) at your core (zhöng),

4. With the eyes and ears acute and clear,

5 And with the 4 limbs fixed,

6 You can thereby make a lodging place (shé) for the vital essence (jing).

7 The vital essence (jing); it is the essence of vital energy (ch’i).

8 When the vital energy (ch’i) is guided, it [jing] is generated.

9 When it (jing) is generated, there is thought.

10 When there is thought, there is knowledge.

11 But when there is knowledge, then you must stop.

12 Whenever the forms of the mind (hsin) have excessive knowledge,

13 You lose your vitality (shêng).

Commentary

Verse 8 provides personal context for the Heaven-Earth-Human synergy that was introduced in the previous verse. It illustrates how the three self-cultivation practices that are associated with the triad are crucial if we are to attract jing to our core. In such a way, the current verse integrates many of the notions from earlier sections of the Nei-yeh.

Lines 1-2:

1 If you can be aligned and be tranquil,

2 Only then can you be stable.

Only by being aligned and tranquil can hsin, our heart-mind, become stable. This statement evokes the 3 ruling principles of the Heaven-Earth-Human metaphor. The aligning process of Heaven and the calming process of Humans are essential if we are to engage in the stabilizing process of Earth.

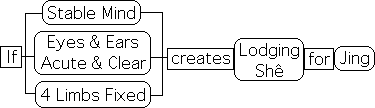

Lines 3-6:

3 With a stable mind (hsin) at your core (zhöng),

4 With the eyes and ears acute and clear,

5 And with the 4 limbs fixed,

6 You can thereby make a lodging place (shé) for the vital essence (jing).

These lines delineate the 3 necessary conditions for creating a lodging place (shé) for jing, the generative energy: 1) a stable mind (hsin) presumably from tranquility and alignment, 2) eyes and ears acute and clear, and 3) four limbs fixed.

This is the first verse that makes an apparent reference to sitting meditation. The 'four fixed limbs’ sets the context for a stable mind and clear/acute senses, i.e. eyes and ears. In agreement, Roth reads the verse and entire Nei-yeh as an ancient meditation manual.

The word that Roth translates as ‘fixed’ could also be translated as ‘firm’. In this case, the verse might be understood as referring to a synergistic complex of physical practices, which might include quietude, Tai Chi, and/or Chi Gung-like exercises.

In contrast to most forms of meditation, the senses, i.e. eyes and ears, are not blocked, but instead are still engaged, i.e. ‘acute and clear’. Rather than motivating desires, they seem to be in a quiescent state of observation. This ‘open eyed’ meditation could be a general type of unfocussed awareness that is associated with readiness for any eventuality.

The text is beginning to answer the unspoken question from Verse 1. How do we get jing to reside in the center (zhöng) of our chest, i.e. hsin (heart-mind), so that we can become a Sage? The above-mentioned practices are designed to cultivate both an aligned body and tranquil mind. This process creates an attractive internal space that invites jing (life force) into our core (zhöng).

Line 7:

7 The vital essence (jing); it is the essence of vital energy (ch’i).

The initial lines instruct us how to create an internal lodging place (shé) for jing. Creating a welcoming space is important because of the relationship between the powerful jing and ch’i energies. Jing is the essence of ch’i.

![]()

These word-concepts have an all-encompassing significance in Chinese philosophy. Traditionally, both ch’i and jing have universal and physiological aspects. They permeate the both macrocosm and the microcosm. On the universal, jing animates life and spirits, while ch’i animates the cosmos. On the physiological level, jing is associated with sexual energy, while ch’i with breath. What is the significance of their relationship?

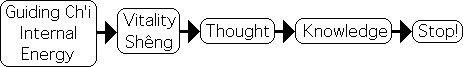

Line 8:

8 When the vital energy (ch’i) is guided, it [jing] is generated.

Having jing in our core presumably results in ch’i. But this is not enough. According to line 8, we must guide ch’i. Why?

According to Roth, our translator, ‘guiding ch’i’ generates jing, which he indicates by his brackets. However lines 8 through 11 have a parallel logical construction that doesn’t include jing. Following is a more literal translation that emphasizes this logical pattern.

8 Guiding ch’i results in vitality (shêng).

9 Vitality (shêng) results in thoughts.

10 Thoughts results in knowledge.

11 Knowledge results in the necessity of stopping.

In this version, ‘guiding ch’i’ results in vitality (shêng) rather than ‘generating jing’.

What does ‘guiding ch’i’ entail? Recall from Verse 2 that the te/yi synergy is required to ‘secure, welcome and stabilize’ the elusive ch’i energy. By extension, ‘guiding ch’i’ could be accomplished by employing te and yi to both restrain and direct our mental energy. Note that this process is intentional. Rather than passively allowing it to wander, we must engage in actively ‘guiding ch’i’ in order to enhance our personal vitality.

Lines 9 and 10 indicate the consequences of these processes. Vitality results in thinking, which in turn results in knowledge. Knowledge certainly seems to be a positive outcome. But is it? Line 11 counsels us to stop after knowledge. What does this mean?

Lines 11-13:

11 But when there is knowledge, then you must stop.

12 Whenever the forms of the mind (hsin) have excessive knowledge,

13 You lose your vitality (shêng).

The final lines of the song-poem warn us of the dangers of too much knowledge. Paraphrasing: ‘Vitality (shêng) results in thoughts and then knowledge. But we must stop the process of knowledge generation before it becomes excessive. Excessive knowledge harms our vitality.’ We must moderate, even halt, this knowledge generation process in order to protect our vitality. This is an example of how unrestrained vitality can actually be detrimental to our health.

![]()

How do we halt this process? Could te, self-restraint, be the key?

This thought chain evokes the notion that extreme exuberance can be damaging. Filled with vitality, we begin connecting dots, perhaps too many. Unrestrained thinking that is imbued with energy can generate negative scenarios that frighten and give us anxiety. Global warming, world wars, runaway fires, and insufficient resources are just a few of the many types of knowledge that can give us nightmares, thereby eroding our vitality (shêng). Some times we can simply ‘know’ too much.

Guiding Ch’i = Tao-yin

Line 8 suggests that 'guiding ch’i' results in personal vitality (shêng). It is evident that the Nei-yeh considers 'guiding ch’i' to be a significant method of enhancing personal energy. What does it mean to 'guide ch’i'?

The footnote that Roth associates with his translation of this line provides some insights into the meaning.

"53. Riegel would emend tao to t'ung because of similar form corruption. While this is possible, I think that Chao Shoui-cheng's emendation better suits the semantic context here. His suggestion of tao is the tao of the tao-yin, the guiding and pulling exercises to circulate the vital breath (ch’i) that are referred to in both the Chuang Tzu 15 and Huiai-nan 7 and in texts excavated from Ma-wang-tui and Chang-chia-shan. While I do not think that these physical exercises are being suggested here, I do think that the guiding of the vital breath (ch’i) while seated is what this line, and the entire verse is talking about."1

According to Roth's understanding, 'guiding ch’i' is associated with 'tao-yin', i.e. physical practices that consist of 'guiding and pulling exercises to circulate the vital breath (ch’i)'. A number of significant traditional Taoist texts refer to these physical practices. Due to the reference to ‘4 limbs fixed’ in line 5, Roth suggests that this particular verse is referring to the breath regulation that occurs in stationary meditation, whether sitting or standing.

As mentioned, rather than ‘fixed’, the 4 limbs could also be ‘firm’. Under this interpretation, the verse could be referring to controlling the breath while performing deliberate physical exercises, perhaps proto-Tai Chi. While practicing Tai Chi, we must concentrate on integrating our breath with the movement of our legs and arms, which are flexible, firm and light. Indeed the expression ‘iron in silk’ reflects this relationship.

Whether sitting or active, ‘guidingch’i’ seems to include intentionality. On the particular level, it is essential to consciously move ch’i, i.e. the breath, around our respiratory system while meditating. In a larger context, consciously guiding this cosmic energy source throughout our body evokes personal vitality.

It is not enough to behave or move automatically. Inadvertently going through the motions is insufficient. To get the added benefit, we must intentionally move ch’i through our bodily channels, from our fingertips to toes.

As a personal example of the benefits of ‘guiding ch’i’: as an organist, it is not enough to simply play the notes correctly, I must guide and shape the notes to create music, i.e. beauty through sound. While playing mechanistically is enervating, infusing the notes with intentionality is invigorating. In general, a reactive life is boring, while leading a proactive life is stimulating. These are simple day-to-day examples of how ‘guiding ch’i results in vitality (shêng)’.

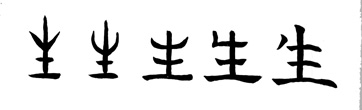

Shêng (Vitality): Ideogram

The ideogram for shêng plays an increasingly significant role in the Nei-yeh. We’ve already seen it frequently in these first 8 verses. Growing in significance, it will be the main focus of three of the final verses.

Shêng’s ideogram has a variety of different usages. For our purposes, it has three basic meanings: generation, vitality and/or life. The 3rd verse stated that vitality (shêng) is mind’s (hsin) natural condition, if undisturbed by excessive emotions and desires. Put in a positive fashion, a tranquil mind is filled with generative capacities, i.e. vitality. Shêng is combined in a positive manner with both tranquility and mind.

In the 6th verse we see it again. Paraphrasing: people flourish (shêng) when filled with the Tao. In this verse, Humans, the Tao and shêng have a positive interaction. Perhaps, the Way of self-cultivation is a source of human vitality.

In the current verse, shêng is employed three times: each time in a highly significant fashion. In the first, shêng is with the result of ‘guiding ch’i’. This phrase means a lot to me as a musician, as it seems to identify what it is to ‘play music’ vs. ‘hitting the correct notes’. Intention, i.e. guiding, is required to take it from the mechanical reproduction of sound to the actual production of music.

Then shêng as vitality is associated with thinking and then knowledge. Thought and the pattern recognition associated with knowledge are natural byproducts of feeling good. However, there are limits. We see shêng again at the very end of the verse. Summarizing briefly for this context: ‘Vitality (shêng) results in thoughts and then knowledge. But stop before going too far. Excessive knowledge results in losing vitality (shêng).’ The Nei-yeh provides a cautionary warning. These lines seem to imply that we must restrain vitality from depleting itself in excess. Overenthusiastic, we overdo it and harm our health.

As seen, shêng is a significant concept of Nei-yeh. In fact, shêng appears almost as many times as the Tao and more than any other ideogram except hsin. Could shêng as vitality be the primary goal of inner cultivation?

Let us trace its development as an ideogram to get a better notion of its flavor. It began as a small plant (signified by a vertical line with a upward leaf-like curve on both sides) that is growing from the ground (signified by a horizontal line). The entire image suggests a sprout. To indicate that the plant was continuing to grow, another horizontal line was added between the sprout at the top and the ground at the bottom. This growing plant eventually became the ideogram for vitality.3

With this image in mind, we can better understand shêng’s dictionary definitions. ‘shêng: giving birth to, generate, grow, sprout, light (a fire), living, existence, emotion, life, livelihood’. Associated with initial growth, not flowers or fruit, shêng can also mean ‘unripe, green or raw’4 or ‘unusual, unripe, unpolished’.6 In other words, the vitality has not come to fruition. Its raw potentials are vast.

This nuance has a significant implication. The vitality that emerges due to self-cultivation is undirected and unrefined. The Nei-yeh does not prescribe any particular course of behavior for this internal energy, for instance kind, generous, ambitious, or inspired. Each human, whether artist, musician, mother, politician, athlete or warrior, can manifest this inner vitality (shêng) in any way that seems appropriate.

Spirit House Metaphor: Create a tranquil internal space to attract cosmic energies

Verse 8 is the first, but not the last, verse that makes explicit use of what we shall call the ‘spirit house’ metaphor. The Nei-yeh counsels us to create the appropriate conditions in order to establish a lodging place (shé) for jing, one of the highlighted cosmic energies that we want to attract to our core. Rather than a primitive belief system, we believe that this metaphor is an effective way of conceptualizing a complex aspect of human existence. Let’s see why.

All systems of thought are rough approximations that attempt to make sense of a confusing reality. Personal vitality is one of those aspects of existence that is frequently baffling, especially as we age. One moment we have an abundance of energy to accomplish our daily tasks and then suddenly exhaustion sets in. As a writer and musician, sometimes every note and word is perfect, while other times my fingers can’t seem to find the correct organ keys and my mind searches endlessly for the proper verbiage. Briefly put, physical vitality and mental acuity seem to come and go, somewhat erratically.

The erratic nature of personal energy seems to be a feature of the human condition. In our science-dominated contemporary culture, we generally attribute the irregular nature of vitality and inspiration to internal biological forces. We blame our periodic lapses on lack of sleep, poor diet, insufficient exercise or merely aging.

Rather than an exclusively biological explanation, the ancient Chinese that composed the Nei-yeh conceptualized these lapses in an anthropomorphic fashion. They characterized these personal energies as beneficent spirits that come and go from an internal lodging place (shé). The verses frequently repeat that these cosmic forces, such as the Tao, ch’i and jing, can’t be seen, heard or sensed. However, we can perceive their effects in the world around us. Rather than being ghosts, these spirits can be likened to positive energies that will increase our vitality.

In proactive fashion, the ancient Chinese posed some pertinent questions. How do we get these spirits to come and stay? What techniques or procedures will attract these cosmic energies to us? What kind of characteristics must this dwelling possess if it is to both attract and stabilize these spirit energies? Posing the same questions from our contemporary perspective: How do we stabilize our physical and mental vitality?

According to the Nei-yeh, we must attract these positive spirit energies, whether Tao, jing, ch’i, or shên, to us rather than actively pursuing them. Although accessible at all times, we can’t just tap into these powers through force of will or physical exertion. Instead we must create the proper conditions to entice them to us.

Romantic love provides us with a familiar example of this process. Instead of purchasing it at a department store or online, we must attract love to us. We go to locations with potential and even attempt to look physically attractive in order to entice the right someone to be our romantic partner. After meeting a potential love mate, we then attempt to stabilize the relationship by engaging in proper behavior.

In similar fashion, we must both attract and stabilize these cosmic energy forces in our center. We entice them by providing an empty space for them to reside or abide. While mental disturbance repels them, a tranquil mind attracts them.

Many Southeast Asian households have spirit houses and shrines complete with water, food, flower garlands and even pictures. These spirit houses are designed to attract positive spirits, most frequently the spirits of their ancestors. According to the Nei-yeh, we must create an internal spirit house to attract these vital energies.

To indicate this internal ‘lodging place’, the Nei-yeh regularly employs the Chinese word shé. Just as with any quarters, shê must be inviting in order to attract cosmic visitors. The ideogram for shé even looks like a spirit house.

The advantages of these energies, such as vitality and inspiration, don’t arise merely from a good diet and proper exercise, but instead require internal emptiness. Daily practices are necessary if we are to create the empty space that attracts these elusive cosmic energies. According to the Nei-yeh, we must both align our body and cultivate a tranquil mind in order to stabilize the cosmic forces at our center. Once stabilized, these energies are the source of vitality.

Summary

Verse 8 examines the nature of jing in greater depth than prior verses. By cultivating alignment and tranquility, stability is created. These are the 3 ruling principles of the Heaven/Earth/Humans triad. This inner stability combined with firm limbs and senses that are acute and clear creates an internal space (shé) for jing. These meditation-like processes attract jing, which is the essence of ch’i. ‘Guiding ch’i’ results in vitality (shêng). Inner vitality generates thoughts and knowledge. The generation of knowledge must be moderated to avoid harming vitality. If vitality is unrestrained, it can actually damage itself. These are powerful concepts.

Footnote

1 Roth, p. 221

3 Chinese Characters, Dr. L. Wieger, S. J., Dover Publications, first published 1915, this edition 1965, p. 203

4 Concise English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 397

5 Chinese Calligraphy, Edoardo Fazzioli, Rebecca Hon Ko, Abbeville Press, 1986, p. 52

6 Chinese Characters, Dr. L. Wieger, S. J., Dover Publications, original 1915, 1965, p. 638