Nei-yeh (Chinese Self-Cultivation Manual)

15. Preserve Life Force (jing) for Natural Vitality

1 For those who preserve and naturally generate vital essence (jing)

2 On the outside a calmness will flourish.

3 Stored inside, we take it to be the well spring.

4 Floodlike, it harmonizes and equalizes

5 And we take it to be the fount of vital energy (ch’i).

6 When the fount is not dried up,

7 The four limbs are firm.

8 When the well spring is not drained,

9 Vital energy (ch’i) freely circulates through the nine apertures.

10 You can then exhaust the heavens and the earth

11 And spread over the four seas.

12 When you have no delusions within you,

13 Externally there will be no disasters.

14 Those who keep their mind unimpaired within,

15 Externally keep their bodies unimpaired,

16 Who do not encounter heavenly disasters

17 Or meet with harm at the hands of others,

18 Call them Sages (sheng).

Commentary

Verse 15 proclaims the virtues of preserving jing. It also refines issues first posed in Verse 1. How to become a Sage? Recall that those that have jing (life force) at their center are Sages. Conserving this life force seems to be of utmost importance, if one is to become a Sage.

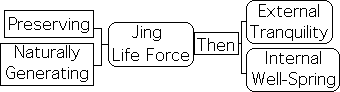

Lines 1-3:

1 For those who preserve and naturally generate vital essence (jing)

2 On the outside a calmness will flourish.

3 Stored inside, we take it to be the well spring.

Preserving and naturally generating jing results in external calm and an internal 'well-spring'.

Conservation of life force could be likened to generating energetic capital. Continually spending this capital means that there will be no reserves in case of emergency. More importantly, there will be no accumulation that is compounding interest. The remainder of the verse suggests the results of this compounding life force (jing).

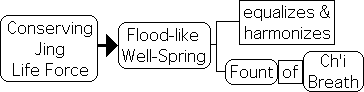

Lines 4-5:

4 Floodlike, it harmonizes and equalizes

5 And we take it to be the fount of vital energy (ch’i).

Conserving jing with its resultant accumulation becomes an internal, ‘flood-like’ wellspring of energy. This abundant vitality both ‘harmonizes and equalizes’. This harmonizing and equalizing process presumably benefits self, family and community.

Just as significantly, nurturing jing in this fashion becomes the ‘fount of ch’i.’ Under this perspective, jing and ch'i differ only in degree, not in kind. An accumulation of jing (generative energy) actually becomes ch'i. Rather than just breath, ch'i, in this case, probably refers to the universal cosmic energy that permeates existence. In other words, preserving our personal jing enables us to tap into a more universal energy.

Line 5 reinforces and refines the notion that jing is the essence of ch’i from verse 8. Not just any kind, it is ‘nurtured jing’ that stimulates ch’i flow.

Lines 6-7:

6 When the fount is not dried up,

7 The four limbs are firm.

These 6 lines speak of the benefits of conserving jing with its resultant well-spring of energy. If this fount of jing is not dried up, the body’s 4 limbs are firm, i.e. not feeble or sickly. As we shall see, there are many ways to over spend our life force – too much of anything: thinking, talking, sex, exercise, and even emotional turbulence.

![]()

Lines 8-11:

8 When the well spring is not drained,

9 Vital energy (ch’i) freely circulates through the nine apertures.

10 You can then exhaust the heavens and the earth

11 And spread over the four seas.

If the well spring of jing is not drained, presumably from over consumption, ch’i flows freely through the 9 apertures encompassing the totality: all under Heaven and Earth’s breadth. Abundant ch’i flow seems to be another advantage to accumulating jing capital.

![]()

Evidently ch’i flow is not confined to the body. The passage refers to ch’i flow through the body’s 9 apertures. These include all of our body’s openings to the external world, the 7 sense apertures in our head, 2 nostrils, 2 eyes, 2 ears, 1 mouth, plus our anus and vagina/penis.

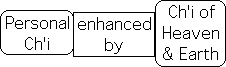

We take this to mean that ch’i energy is exchanged freely with the external world. In addition to our body’s ch’i flow, we are able to tap into the ch’i of both Heaven and Earth.

According to the Chinese belief system, the interaction of Heaven and Earth creates Humans. It is important to both balance and cultivate the energies from these 2 fundamental sources. How do we cultivate these energies?

As Master Ni said: “Should practice sung/relaxation at all times. If any tension anywhere in Body, then Energy from Heaven and Earth will be blocked at that point.”

This Ni quotation suggests there is permeability between our Body and the external world. In other words, the Body’s energy is not merely biological. If we are mentally and physically relaxed, we can partake of external energies, i.e. those of Heaven and Earth. Presumably if our body is aligned and our mind is tranquil, we will be relaxed enough to tap into this universal power source. In terms of this verse, Sages are those who are able to release tension to experience the energy of Heaven and Earth.

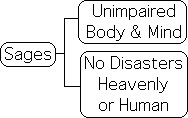

Lines 12-18:

12 When you have no delusions within you,

13 Externally there will be no disasters.

14 Those who keep their mind unimpaired within,

15 Externally keep their bodies unimpaired,

16 Who do not encounter heavenly disasters

17 Or meet with harm at the hands of others,

18 Call them Sages (sheng).

The verse ends with the characteristics of the Sage, presumably someone who has nurtured his or her jing (life force). Those who maintain an unimpaired body and mind (hsin), i.e. no delusions, don’t experience natural disasters or harm from others. These people are Sages.

Nurturing Jing, Ch’i & Shên: a Millennia-long Practice

This verse emphasizes a significant feature of the Chinese self-cultivation tradition: preserving and naturally generating jing (life force). Although jing arises spontaneously if the conditions are right, we must still preserve our life force. Put in the negative, we must avoid spending all of this naturally generated energy and instead save some in reserve.

While this verse stresses the importance of nurturing jing, the Taoist tradition holds that we must nurture the other cosmic energies, ch’i and shên, as well. The importance and practice of nurturing these 3 energies continues into the 21st century. Following is an example from a significant sword manual written in the early 20th century. It was important enough that the work was translated into English early in the 21st century.

The following quotation from the book indicates how to ‘avoid leakage’ of this trio of vital energies. As an indication of the importance of this practice, ‘avoiding leakage’ is placed as the ‘highest principle’ of the internal martial arts.

“Those who practice the internal martial arts should place 'no leakage' as the highest principle: they need to preserve their essence – Jing – and nurture their vital energy – Qi. Besides they need to calm their spirits – Shen – and hold the "unison of yin/yang energies" as the guideline for regulating their Qi."

"Too much sex will scatter your Jing and Qi and scatter your Shen. 'No leakage' also refers to refraining from sending out too much of your own Qi - working too hard, staying up too late or even talking too much."1

‘Preserving jing’, ‘nurturing ch’i (qi)’, and ‘calming shên’: It almost seems as if this quote could be an addendum to the Nei-yeh. The commentary adds some insights not included in our ancient text. ‘Too much sex’, ‘working too hard’, ‘staying up too late’ and ‘talking too much’ also result in the ‘leakage’ of these cosmic energy sources.

Notice that the ‘leakage’ does not result from the highlighted activities, but from ‘too much’ of them. Normal behavior is not the problem, just an excess. Maintaining the center, the balance, avoids leakage of the energies that are the basis of our vitality.

These 20th century references hark back to processes first enunciated in book form in the Nei-yeh. As an indication of the continuity of the Taoist tradition, jing, ch’i and shên, the Nei-yeh’s primary energies, are still frequently referred to as the jewels of self-cultivation practices.

Jing (Life Force) & Shêng (Vitality)

In the Nei-yeh, the first line is generally highly significant in that it tends to identify the topic of the verse. The current verse #15 follows this pattern. The first line consists of 4 ideograms, which can be literally translated as ‘life force (jing)’ - ‘preserving’ - ‘natural’ - ‘vitality (shêng)’. In this raw form, the process of ‘preserving jing’ is linked with ‘natural vitality’. This rough translation provided us with the title for this verse.

Together the two could also easily mean ‘generating life force’. Generation is a key state that virtually everyone would desire. Nobody wants to degenerate. Well into maturity, I certainly would like to tap into the positive energy of jing shêng.

Shêng and jing are linked in an even more intimate manner. Originally, as reported, jing’s ideogram consisted of the ideogram for shêng on the top and the symbol for well on the bottom. This linkage suggested to us that jing is the well-spring of life (shêng). In support of this interpretation, this verse states that jing is the well-spring of ch’i. Whether as a pair or connected in a common ideogram, jing and shêng are integrally related. Indeed, life force and vitality seem a natural combination.

What is the difference, if any, between jing (life force) and shêng (vitality)? Are they synonymous? Or do the two ideograms have a slightly different meaning?

The Nei-yeh frequently combines the ideograms for jing and shêng. Roth accurately translates the two words in this line as ‘generating life force’. The document also regularly separates the two words, in which they are translated as ‘life force (jing)’ and ‘vitality (shêng)’.

While very similar, the two words are not quite interchangeable. We suggest that jing is an energy source that fuels the positive state of personal vitality. In other words, jing is a cosmic energy, while vitality is a personal state that depends upon this cosmic energy. Later verses emphasize this distinction.

Footnotes

1 Huang Yuan-xiou, The Major Methods of Wudang Sword, originally published 1930. Dr. Lu Mei-hui translator, Master Chang Wu Na commentary