Nei-yeh (Chinese Self-Cultivation Manual)

Verse 24. Meditation results in Thoughts & Deeds from Heaven.

1 When you enlarge your mind and let go of it,

2 When you relax your vital breath (ch’i) and expand it,

3 When your body is calm and unmoving,

4 And you can maintain the One and discard the myriad disturbances:

5 You will see profit and not be enticed by it;

6 You will see harm and not be frightened by it.

7 Relaxed and unwound, yet acutely sensitive,

8 In solitude, you delight in your own person.

9 This is called "revolving the vital breath (ch’i)":

10 Your thoughts and deeds seem heavenly.

Commentary

Verse 24 seems to be about meditation and its benefits.

Lines 1-6

1 Enlarging your mind and letting go of it,

2 Relaxing your vital breath (ch’i) and expanding it,

3 When your body is calm and unmoving,

4 Maintaining the One and discarding the myriad disturbances:

5 You will see profit and not be enticed by it;

6 You will see harm and not be frightened by it.

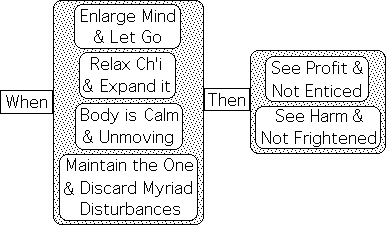

Engaging in 4 meditation-like processes yield positive results. The practices: 1) ‘enlarging and letting go of hsin (the heart mind)’; 2) ‘relaxing and expanding ch’i (the breath)’; 3) ‘a calm and unmoving body’; and 4) ‘maintaining the One and discarding the myriad disturbances (the 10,000 things)’. Following these practices results in ‘seeing profit and not being enticed’ and ‘seeing harm and not being frightened’.

Let’s discuss these practices in a little more detail. ‘Enlarging and letting go of hsin’ suggests an ‘open mind’, i.e. cognition that is not cluttered with dogma of any variety. This interpretation is certainly congruent with the enduring Taoist tradition, which has always stressed practices over ideas. Perhaps cultivating (enlarging) the ‘non-verbal mind within mind’ from Verse 14 enables us to ‘let go’ of the judgmental verbal mind that is so limiting.

‘Relaxing and expanding ch’i’ seems to entail two consecutive processes. On the meditative level, the line is probably referring to relaxing and expanding the breath (ch’i). Because ‘relaxing ch’i’ precedes ‘expanding ch’i’, we must first relax our energy in order to expand breath throughout our respiratory system. Proper order is of utmost importance in Chinese thought and culture.

This line could also have other meanings. Relaxing is an incredibly important feature of Tai Chi, music, athletics and the martial arts. Relaxation is correlated with speed, which is correlated with power. Conversely, tension restricts the free-flowing energy that is the root of any art.

‘Expanding ch’i’ evokes the insights of Verse 15. Preserving jing results in flood-like ch’i that flows through our 9 apertures to merge with the universal ch’i of Heaven and Earth. ‘Expanding ch’i’ could certainly result in this abundant ch’i flow that connects the cosmos.

‘A calm and unmoving body’ certainly suggests the practice of meditation or quietude.

‘Maintaining the One and discarding the myriad disturbances’ harks back to Verse 9. The One could be the Way, the ideal self-cultivation practices called the Tao. The One could also be the integration of the cosmic energies jing, ch’i and shên. In the context of the verse, the line could mean ‘maintaining’ the focus of meditation, which entails ‘discarding’ the countless disturbing thoughts that continually plague our tranquility. Guiding (yi) and restraining (te) are equally important.

Lines 7-8

7 Relaxed and unwound, yet acutely sensitive,

8 In solitude, you delight in your own person.

These complementary lines balance community and solitude. The word that Roth translates as ‘sensitive’ in line 7 is ren, the ultimate Confucian virtue. Ren is frequently translated as compassion. Ren implies that we are ‘acutely sensitive’ to our community rather than just our internal state. The context of the prior lines plus the consequential character in line 7 imply that ren could develop as a result of self-cultivation. The intentional meditative processes of relaxing and expanding result in this community awareness (ren) that is so important to not just to Confucians, but to Chinese culture as a whole.

The verse’s employment of the Confucian word-concept ren is yet another indication of how the Nei-yeh is not limited to being just a Taoist document, but instead represents the more inclusive category of Chinese wisdom.

Line 8, ‘in solitude, we delight in our own person’, evokes the image of the joyful state of solitary meditation; or it could just be the enjoyment of being alone, i.e. without others. Paired with ren’s implication of community from the preceding line, the Nei-yeh seems to be suggesting pulses of solitude, rather hermit-like isolation.

Lines 9-10:

9 This is called "revolving the vital breath (ch’i)":

10 Your thoughts and deeds seem heavenly.

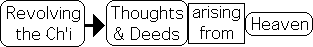

This practice is called ‘revolving the ch’i’. If we engage in this solitary practice, our thoughts and deeds seem to originate from Heaven. Again rather than stressing ideas, dogma and social indoctrination, the Nei-yeh suggests that practicing self-cultivation naturally results in positive thoughts and deeds.

This indirect approach to behavior permeates the Nei-yeh. The implicit belief is that delineating right and wrong behavior won’t help, if hsin, the heart mind, is corrupted. Proper ‘thoughts and deeds’ are instead founded in maintaining the Tao, the ideal self-cultivation practices, which include ‘revolving the ch’i’.

Over 2 millennia later, Master Ni stressed the importance ‘revolving the ch’i’ while meditating. In a series of Taoist meditation classes, he taught us to both regulate our breathing and mentally direct ch’i through the ‘macro and micro-cosmic orbits’, i.e. the body’s meridians or channels.

This continuity is yet further evidence of the enduring nature of the Nei-yeh’s philosophical framework. While the Nei-yeh may have been the first such self-cultivation manual, it is a repository of wisdom that was probably around for centuries before it was written down. This wisdom has permeated Chinese thought for thousands of years – up through current times.