8. Nei-yeh 23 >26

- Verse 23. Tao of Eating: When full, stop eating. When hungry, don’t think of food.

- Verse 24. Meditation (‘revolving the ch’i’) results in thoughts & deeds from Heaven.

- Verse 25. Tranquility & alignment (Ching & Cheng) provide the Tao, the source of vitality (shêng) & good fortune, a quiet place (shé) to settle.

- Verse 26. Ch’i remains in a tranquil mind (hsin ching), which is the result of following the Tao of restricting our sense-desires.

- Master Ni on Ch'i, Mind and Desires

Introduction

Verse 23. Tao of Eating: When full, stop eating. When hungry, don’t think of food.

- For all the Way [Tao] of eating is that:

- Overfilling yourself with food will impair your vital energy [ch'i]

- And cause your body to deteriorate.

- Overrestricting your consumption causes your bones to wither

- And the blood to congeal.

- The mean between overfilling and overrestricting:

- This is called "harmonious completion".

- It is where the vital essence (jing) lodges

- And knowledge is generated.

- When hunger and fullness lose their proper balance

- You make a plan to correct this.

- When full, move quickly;

- When hungry, neglect your thoughts;

- When old, forget worry.

- If when full you don't move quickly,

- Vital energy (ch'i) will not circulate to your limbs.

- If when hungry you don't neglect thoughts of food,

- When you finally eat you will not stop.

- If when old you don't forget your worries,

- The fount of your vital energy (ch'i) will rapidly drain out.

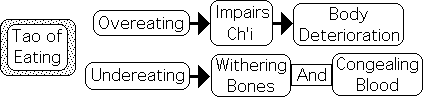

Verse 23 focuses upon the Tao of Eating. Over-eating impairs ch’i flow to causes the body to deteriorate. Under-eating causes the bones to wither and the blood to congeal.

The mean is called ‘complete harmony’. This is where jing resides (our inner spirit house) and knowledge is generated.

![]()

The verse’s middle lines offer a plan to maintain the mean. The final lines delineate the consequences of not following these suggestions.

‘When full, move quickly’, presumably to stop eating. If we continue to eat after we are full, ch’i won’t circulate to our limbs.

![]()

‘When hungry, neglect your thoughts’ presumably regarding food. If we continue thinking about food when we are hungry, we won’t be able to stop eating once we begin.

![]()

‘When old, forget worry.’ If we continue worrying when we get old, our jing, the fount of ch’i, will drain out and dry up.

![]()

Verse 24. Meditation (‘revolving the ch’i’) results in thoughts & deeds from Heaven.

- When you enlarge your mind and let go of it,

- When you relax your vital breath (ch'i) and expand it,

- When you body is calm and unmoving:

- And you can maintain the One and discard the myriad disturbances.

- You will see profit [take advantageo of others v2] and not be enticed by it;

- You will see harm and not be frightened by it.

- Relaxed and unwound, yet acutely sensitive,

- In solitude, you delight in your own person.

- This is called "revolving the vital breath (ch'i)":

- Your thoughts and deeds seem heavenly.

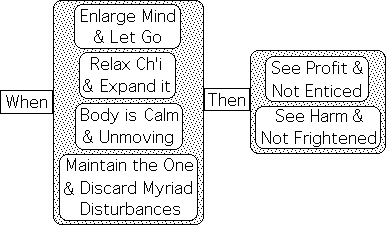

Verse 24 seems to be all about meditation. Enlarge your mind. Relax your breath and expand it. Hold your body still. Maintain the One and discard the myriad disturbances – the 10,000 things. The middle lines enunciate the advantages. Profit won’t entice us and harm won’t frighten us.

Relaxed, yet acutely sensitive, in solitude, we delight in our own person. This practice is called ‘revolving the ch’i’. If we engage in this solitary practice, our thoughts and deeds seem to originate from Heaven.

![]()

Over 2 millennia later, Master Ni stressed the importance ‘revolving the ch’i’ while meditating. In a series of Taoist meditation classes, he taught us to both regulate our breathing and mentally direct ch’i through the ‘macro and micro-cosmic orbits’, i.e. the body’s meridians or channels. This is yet further evidence of the endurance of the Nei-yeh’s philosophical framework.

Verse 25. Tranquility & alignment provide the Tao, the source of vitality & good fortune, a quiet place to settle.

- The vitality (shêng) of all people

- Inevitably comes from their peace of mind.

- When anxious, you lose this guiding thread;

- When angry, you lose this basic point.

- When you are anxious or sad, pleased or angry,

- The Way (Tao) has no place within you to settle.

- Love and desire; still (ching) them!

- Folly and disturbance; correct (cheng) them!

- Do not push it! Do not pull it!

- Good fortune will naturally return to you,

- And that Way (Tao) will naturally come to you

- So you can rely on and take counsel from it.

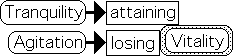

- If you are tranquil (ching), then you will attain it.

- If you are agitated, then you will lose it.1

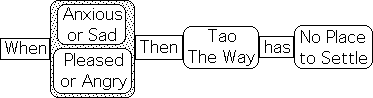

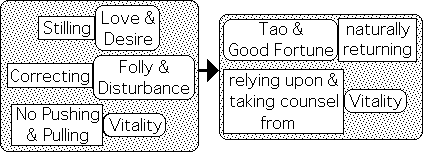

Verse 25 speaks of the relationship between vitality (shêng), the Tao, and the importance of creating a tranquil place (shé). Vitality (shêng) comes from a tranquil mind (ching hsin).

![]()

When our mind is filled with emotions such as anger, anxiety, sadness or even being pleased, the Tao has no place (shé) to settle.

Instead of being subject to love and desire, seek tranquility (ching). Instead of being subject to folly or disturbance, seek alignment (cheng). We can’t force things. Good fortune and the Tao will return naturally, presumably by cultivating ching and cheng. Further this process will stabilize the Tao, so that we can rely upon it and the insights that emerge from its presence (perhaps shên inspired).

This quotation from the Nei-yeh seems to suggest that the Tao is an unseen positive cosmic force that is connected with vitality (shêng) and good fortune. Further the Tao comes and goes depending upon an individual’s state of mind. Mental tranquility appears to attract the Tao – giving it a place to settle. Conversely mental agitation repels the Tao. A prerequisite for the Tao seems to be of ‘peace of mind’.

Mental tranquility excludes anxiety, anger, and sadness, as well as being pleased, love and desire. In other words, both positive and negative emotions drive away the good fortune and vitality (shêng) associated with the Tao.2 Pure mental equanimity is the necessary precondition to draw the Tao and all its positive features into our lives.

Verse 26. Ch’i remains in a tranquil mind (hsin ching), which is the result of following the Tao of restricting our sense-desires.

- That mysterious vital energy (ch'i) within the mind (hsin):

- One moment it arrives; the next moment it departs.

- So fine, there is nothing within it;

- So vast there is nothing outside of it.

- We lose it

- Because of the harm caused by mental agitation.

- When the mind (hsin) can hold onto tranquility,

- The Way (Tao) will become naturally stabilized.

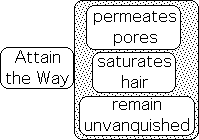

- For people who have attained the Way (Tao):

- It permeates their pores and saturates their hair.

- Within (zhöng) their chest, they remain unvanquished.

- [Follow] this Way (Tao) of restricting sense-desires

- And the myriad things will not cause you harm.

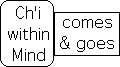

Verse 26 summarizes some important points. The mysterious ch’i within our mind (hsin) comes and goes. Again it is likened to a spirit. Ch’i is so fine and vast that nothing is within or outside of it.

It leaves when our mind (hsin) is agitated.

![]()

When our mind is tranquil (ching hsin), the Way (the Tao) is naturally stabilized.

![]()

Once we attain the Way (Tao), it will permeate our pores and saturate our hair. We will also remain unvanquished. In other words, this ideal self-cultivation process will exhibit a positive effect upon both our physical body and our emotional state.

If we follow the Way (the Tao) of restricting our sense-desires, then nothing will disturb us. Presumably, if we cultivate a tranquil mind, the mysterious ch’i will remain in our hsin to provide us with vitality.

![]()

Master Ni on Ch'i, Mind and Desires

Master Ni expresses similar sentiments a few millennia later.

Ni: “Where does Ch’i come from?

Ch’i from Mind.

As example: If Mind [is] disturbed, Ch’i [is] rough.

If Mind at peace, Ch’i flows naturally.” (October 2000)

Simply, ch’i flow is disrupted when the mind is disturbed. Conversely, ch’i flows naturally when the mind is tranquil. This is an example of how our mental state influences the operation of our body; in this case our breath (ch’i). Both Master Ni and the Nei-yeh view the body/mind complex as an interactive network.

How do we calm the mind in order to have a natural ch’i flow?

Ni: “Mind is Fire.

Fire always burning.

Burning things up.

Still Mind.

Don’t fan Fire.” (March 25, 2000)

Mind is hsin; Fire can be thought of as our emotions. Instead of fanning (accepting) the Fire of our emotions, we must still our Mind. We must consciously ‘reject’ strong emotions. (V7) We must resist the temptation to add mental fuel to the emotional fire.

Master Ni also directly connects breathing (ch’i), the Mind and desires in a neat little package, as the following quotation illustrates.

Ni: “How can I teach Breathing when it comes from the Mind?

When someone angry - breath rises and becomes quick. Like this.”

He gives a brief demonstration of short shallow breathing.

Ni: “This evidence of how Mind affects Breathing.”

Me: “Mind also affects Body. When nervous, shoulders rise.”

Ni: “Right. How do I teach Breathing, if it comes from the Mind?”

Me: “Train the Mind?”

Ni: “How do I train Mind, when it is independent?

Shoulders rise despite intention. Anger comes without asking.

How do I teach Breathing to the Mind?

Necessary to quiet Mind. But how to quiet Mind?”

Me: “Still desires?”

Excitedly Ni: “Right. But how to still desires, when Mind desires what it sees?

Has to do with growth. When plant is weed, must cut down.

Weed like desires that Mind feeds. No attention, no weeds.”

Me: “If Mind cultivates desires, they grow.

Desires disturb Mind, which disrupts Breathing.”

Ni: “Right. Necessary to keep Mind very still and quiet.

For good and bad, not just bad.

Quieting the Mind stills desires. Good for Breathing.” (June 17, 2002)

He states that breath (ch’i) is dependent upon our state of mind. As in the earlier quote, desires disturb the Mind, which disrupt the breath, hence our chi flow. Unfortunately, Mind is independent in that it ‘desires what it sees’.

As a supplement to the Nei-yeh’s framework, Master Ni offers a suggestion as to how to limit these naturally arising desires. He employs the plant metaphor. We cultivate plants by watering them and cutting down weeds. He likens attention to water. Don’t give the weed/desires water/attention and they will naturally die. As before, ‘don’t fuel the Fire’ (of desires) and it will become extinguished.

Footnotes

1 Harold Roth, Original Tao, Inward Training (Nei-yeh), Columbia University Press, 1999, p. 94

2 As an example of the universality of human experience, the Greek philosopher Epicurus and his Roman follower Lucretius also counsel that the individual rejects both positive and negative emotions in order to maximize personal potentials, such as happiness.