Nei-yeh (Chinese Self-Cultivation Manual)

18. Ch’i Flow of Cultivated Mind influences Community naturally

1 When there is a mind (hsin) that is unimpaired within you (zhöng),

2 It cannot be hidden.

3 It will be known in your countenance,

4 And even in your skin color.

5 If with this good flow of vital energy (ch’i) you encounter others,

6 They will be kinder to you than your own brethren.

7 But if with a bad flow of vital energy (ch’i) you encounter others,

8 They will harm you with their weapons.

9 [This is because] the wordless pronouncement

10 Is more rapid than the drumming of thunder.

11 The perceptible form of the mind's vital energy (ch’i)

12 Is brighter than the sun and moon,

13 And more apparent than the concern of parents.

14 Rewards are not sufficient to encourage the good;

15 Punishments are not sufficient to discourage the bad.

16 Yet once this flow of vital energy (ch’i) is achieved,

17 All under Heaven will submit.

18 And once the mind is made stable,

19 All under Heaven will listen.

Commentary

Verse 18 clarifies prior verses regarding ch’i flow and the unimpaired mind (hsin). From Verse 15: ‘Preserving jing’ is a root of abundant ch’i flow. This verse links positive ch’i flow with an unimpaired mind. Verse 10: a well-ordered mind (hsin) naturally exerts a positive influence upon the world. Verse 15: those humans with an unimpaired mind and body are Sages. This verse enumerates the advantages positive ch’i flow and an unimpaired mind.

Lines 1-4:

1 When there is a mind (hsin) that is unimpaired within you (zhöng),

2 It cannot be hidden.

3 It will be known in your countenance,

4 And even in your skin color.

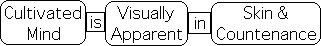

When we have an unimpaired mind at our center (zhöng), it can’t be hidden. It is visually apparent in both our skin and countenance.

‘Completed mind’ is another plausible translation of ‘unimpaired mind’ from line 1. Having completed the cultivation process, hsin has all the positive attributes from prior verses, i.e. well-ordered, tranquil, stable and aligned. Others can perceive this cultivated mind through appearance alone.

Lines 5-8:

5 If with this good flow of vital energy (ch’i) you encounter others,

6 They will be kinder to you than your own brethren.

7 But if with a bad flow of vital energy (ch’i) you encounter others,

8 They will harm you with their weapons.

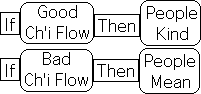

If we have good ch’i flow, others will treat us well. Conversely, if our ch’i flow is bad, others will treat us poorly.

Lines 9-13:

9 [This is because] the wordless pronouncement

10 Is more rapid than the drumming of thunder.

11 The perceptible form of the mind's vital energy (ch’i)

12 Is brighter than the sun and moon,

13 And more apparent than the concern of parents.

Why? The ‘wordless pronouncement’ of mind’s ch’i flow is ‘more rapid than the drumming of thunder’; ‘brighter than the sun and moon’; and ‘more apparent than the concern of parents’. Positive ch’i flow seems to be linked to an unimpaired/cultivated mind (hsin).

The state of our inner ch’i flow naturally emanates from us. Words and actions are secondary. In terms of personal experience, Master Ni’s sheer presence evoked awe and respect, independent of his teachings.

This verse provides the foundation for many of the chapters of the Chuang Tzu. In this book, hunchbacked, deformed and mutilated men are handed and trusted with the keys to the kingdom despite their disabilities or prior crimes. This classic Taoist text never states the reason. The implication is that these men have presumably achieved some kind of inner attainment that inexplicably attracts others to them.

The Nei-yeh provides the rationale behind the mysterious behavior of these rulers. Because of inner cultivation practices, these disabled men have an unimpaired/cultivated mind and resultant positive ch’i flow. Due to their positive energy, these Sages naturally attract others to them.

In a similar context, Chinese painters regularly employed gnarled trees and irregularly shaped boulders to symbolize this perfected ch’i flow.

Lines 14-15:

14 Rewards are not sufficient to encourage the good;

15 Punishments are not sufficient to discourage the bad.

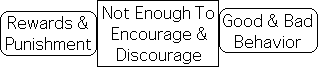

Positive and negative reinforcement is not enough to influence human behavior. This statement has both Taoist and Confucian roots. This syncretism is yet another indication that the Nei-yeh is not exclusively Taoist and should probably be placed in the broader category of Chinese inner cultivation practices. Indeed we suggest that the Nei-yeh is a nascent statement regarding the philosophy behind these practices.

Lines 16-19:

16 Yet once this flow of vital energy (ch’i) is achieved,

17 All under Heaven will submit.

18 And once the mind is made stable,

19 All under Heaven will listen.

Only positive ch’i flow and a stable mind (hsin) will cause all under Heaven to both submit and listen. The last four lines are an exact duplication of the last lines of Verse 10 with one exception. Verse 10 attributes the submission of all under Heaven to one word from a well-ordered mind. This verse attributes it to an unimpaired mind and positive ch’i flow – a refinement.

![]()

Our positive ch’i flow is both visually apparent and also seems to naturally exert a positive influence upon the community. How do achieve this state? From Verse 15: preserving jing is a significant component of flood-like ch’i flow.

Encouraging Yi: Pre-verbal Intentionality

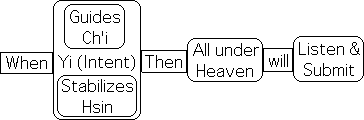

There is another plausible interpretation of the last 4 lines of this verse. The ideogram for yi occurs in both line 16 and 18. Roth emends this ideogram to mean ‘once’, a different yi. We prefer the original meaning - 'mind intent' or 'intention'.

Due to the parallel construction, we could combine the lines to read:

"Guiding ch’i flow and stabilizing hsin (heart-mind) with yi (intention) results in listening and submitting, i.e. hearing and obeying, from those in our community."

This process could apply to many types of interactions. Leaders, teachers, parents and those in relationships of any kind hope that followers, students, children, friends and partners will hear what is being said and then act accordingly. According to this verse, good ch’i flow and a stable psycho-emotional state enhances the chances that students et al. will both ‘listen and submit’.

However to generate this somewhat charismatic internal state, we must apply yi (intentionality) to both ch’i and hsin. From verse 14, yi is pre-verbal – between wuji and taiji according to Master Ni. How do we encourage the development of yi, this non-verbal mental muscle that is so crucial to asserting control over our lives?

Master Ni employed a non-verbal teaching style, which helped to develop this mental muscle. Instead of piling words upon words in explanation, he would first demonstrate the movements and then bid us to copy his form. By emulating his movements, we employed yi, pre-verbal mind intent, to guide our ch’i flow, both lightly and continuously.

It seems that yi is an important component in both our personal growth and Tai Chi. Yi is also crucial for musicianship, the arts, athletics and the martial arts. Each of these disciplines requires pre-verbal intentionality to execute physical actions both quickly and appropriately.

Employing music as an example, it is not enough to play the score’s notes precisely. If we only rely upon our verbal consciousness, the piece sounds calculated and stilted, but without the vitality that leads to enjoyment. It is essential to guide ch’i through fingers, feet and voice via yi in order to really create music. We must transcend the polarities of our verbal mind to effectively apply yi to these disciplines. Only by consistently applying yi will we ever achieve mastery.