Nei-yeh (Chinese Self-Cultivation Manual)

Verse 19. Self-Cultivation results in Insight

1 By concentrating your vital breath (ch’i) as if numinous (shên),

2 The myriad things will all be contained within you.

3 Can you concentrate? Can you unite them?

4 Can you not resort to divining by tortoise or milfoil

5 To know bad and good fortune?

6 Can you stop? Can you cease?

7 Can you not seek it in others

8 Yet attain it in yourself?

9 You think and think about it

10 And think still further about it.

11 You think, yet still cannot penetrate it.

12 While the ghostly and numinous (shên) will penetrate it,

13 It is not due to the power of ghostly and numinous (shên),

14 But to the utmost refinements of your essential vital breath (ch’i).

15 When the four limbs are aligned

16 And the blood and vital breath (ch’i) are tranquil,

17 Unify your awareness (yi), concentrate your mind,

18 Then your eyes and ears will not be over-stimulated

19 And even the far-off will seem close at hand.

Commentary

Line 1-2:

1 By concentrating your vital breath (ch’i) as if numinous (shên),

2 The myriad things will all be contained within you.

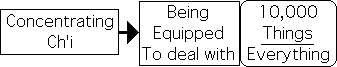

Concentrating ch’i, as if shên, results in being equipped to deal with the 10,000 things - everything.

These lines only liken ‘concentrated ch’i’ to shên. However in traditional Taoist thought, refining jing results in ch’i and refining ch’i results in shên.

![]()

Master Ni employed the metaphor of boiling water to describe this process. Practice is the fire that boils, i.e. refines, jing. The pot preserves jing rather than allowing it to dissipate.

Refining and preserving jing results in transforming water into steam. Jing becomes ch’i, as it ascends from the lower tan tien (energy nexus) in the abdomen to the middle tan tien in the chest. As the refinement process continues, ch’i turns into another type of steam and ascends to the head as shên. In such a manner, concentrated, i.e. refined ch’i becomes shên.

Under this perspective, jing, ch’i and shên consist of the same energy, albeit increasingly more refined. Because of this striking parallel between ancient and modern thought, we are going to equate ‘concentrated ch’i’ with shên in this verse.

Although this verse and others treat these three energies as of the same substance, other verses treat them as separate, although linked, energies. In terms of traditional definitions, jing is associated with generative, i.e. sexual, energy, ch’i with breath and shên with cognition/insight. Although related, they are quite different biologically.

Physics provides a way of understanding these differing perspectives. A bicycle transforms biological energy into mechanical energy. Although the energy is the same, the source is very different. The equivalence of different types of energy was a huge leap forward. Similarly, although jing, ch’i and shên are fundamentally different, the energy is the same.

Lines 3-8:

3 Can you concentrate? Can you unite them?

4 Can you not resort to divining by tortoise or milfoil

5 To know bad and good fortune?

6 Can you stop? Can you cease?

7 Can you not seek it in others

8 Yet attain it in yourself?

A set rhetorical questions pose significant challenges. Can you concentrate ch’i presumably to unite ch’i and shên? Can you avoid employing divination to know the future? Can you stop, perhaps bad habits? Can you cease seeking it in others and rather attain it in yourself?

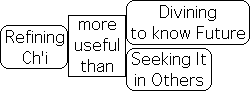

Divination and looking to others for truth seems to be subordinated to the self-cultivation practice of ‘concentrating ch’i’. This statement is fairly radical, especially for the fourth century BCE. Divinatory practices such as the I Ching were widespread and standard practice for all Chinese, regardless of social position. Plus the Chinese were regularly counseled to seek wisdom from others, perhaps the community, a spiritual master, the ancients or books. These lines suggest that attaining ‘concentrated ch’i’ is more useful and important than both ‘divining to know the future’ and ‘seeking it in others’.

Lines 9-14:

9 You think and think about it

10 And think still further about it.

11 You think, yet still cannot penetrate it.

12 While the ghostly and numinous (shên) will penetrate it,

13 It is not due to the power of ghostly and numinous (shên),

14 But to the utmost refinements of your essential vital breath (ch’i).

This section deals with thoughts. Sometimes we keep thinking about something over and over again without any solution – an endless loop. The ‘ghostly and numinous’ from lines 12 and 13 refer to the entirety of spirits, both internal and external. The Chinese believed that we must channel and appease these spirits for both health, insight and good fortune. While it might seem that these earthly ghosts and heavenly spirits provide the answer, it is instead due to the ultimate refinement of ch’i. In other words, concentrated ch’i can penetrate things that are inaccessible to deliberate thought.

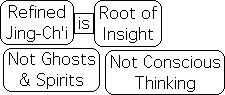

While Roth translates Line 14 as ‘utmost refinements of your essential ch’i’, another plausible translation is the ‘utmost refinement (limit) of jing-ch’i’. Recall from Verse 15 that ‘preserving jing’ is the ‘fount’ for ‘flood-like ch’i’. Instead of coming from the spirit world, answers are revealed when the jing-chi process reaches its limit. ‘Concentrating ch’i’ by ‘preserving jing’ is the real root of insight.

Modern science offers a partial physiological insight into this relationship. Ch’i is related with breath and blood flow, and shên with our cognitive abilities. It is a proven scientific fact that oxygenation improves our mental skills. No matter how smart we are, our cognitive performance suffers when there is not enough blood flow to the brain.

Lines 15-19:

15 When the four limbs are aligned

16 And the blood and vital breath (ch’i) are tranquil,

17 Unify your awareness (yi), concentrate your mind,

18 Then your eyes and ears will not be over-stimulated

19 And even the far-off will seem close at hand.

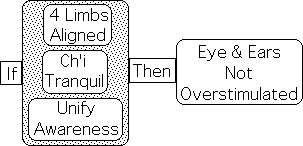

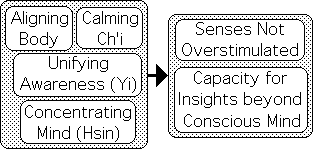

What is the process for refining/concentrating ch’i in order to attain this state of insight (L14) and readiness (L2)? Aligning (cheng) our 4 limbs, calming (ching) ch’i, unifying awareness (yi), and concentrating our mind (hsin), has two results. The eyes and ears, i.e. senses, won’t be over-stimulated and the far off will seem close at hand.

What does ‘over-stimulated senses’ mean? From Verse 12, we know that external things disrupt the senses. In turn, these over-stimulated senses disrupt hsin, the heart-mind. This mental disruption drives away shên, the source of intuitive understanding. In brief, over-stimulated senses undermine our potential for insight.

How about: ‘the far off will seem close at hand’? In the context of this verse, this is perhaps the capacity to have insight into things that are beyond the conscious mind, i.e. those things that we have thought about over and over again without any solution.

And what about the entire passage? The four processes that lead to these presumably positive results are all internally focused self-cultivation practices. ‘Unifying awareness (yi)’ is one of the processes that limits our senses. If yi is not unified, it can attach to any random attraction. We then inadvertently employ this pre-verbal mental muscle to pursue our sensual desires. Conversely, if we focus our awareness yi on these meditation and/or Tai Chi-like practices, i.e. aligning the body, calming the breath, and concentrating the mind, it redirects our attention away from the fulfillment of external desires and towards inner cultivation.

Limiting our sense-desires presumably allows us to concentrate our ch’i. Refining ch’i is linked to shên, which in turn is linked with the non-verbal/intuitive understanding that is the root of insight and even inspiration (V12) – the capacity for insights beyond what the limits of conscious mind.

From Verse 13, we also know that shên’s presence is required for a well-ordered mind (hsin) that leads to a well-ordered community. It seems that shên leads to insight and is a positive organizational force – both desirable features. However, the deep insights of shên are rooted in the inner cultivation practices associated with refining jing-ch’i.