2. Nei-yeh 1>3: Introducing Jing, Ch'i & Hsin

- Inherent Ambiguity of Ancient Chinese Text

- Nei-yeh's 26 Verses are Developmental

- Verse 1. Jing stored in the chests of Sages .

- The Ideogram for Sage (sheng)

- Jing: Definitions & Ideogram

- Verse 2. Te + Awareness attracts Ch’i; Developing Te stabilizes Ch’i.

- Welcomed by Awareness (Yi)

- Complementary Muscles: Physical & Mental

- Ideogram for Ch’i

- Verse 3. Hsin naturally filled with vitality (shêng) & balance; Emotions disrupt natural perfection.

- Hsin: the Ideogram

- Verses 1>3: Summary

Complied in the 3rd century BCE, the Nei-yeh is an inner cultivation manual that exerted a significant influence upon both Taoists and Confucians of the Warring States Era. The texts and philosophies from this time stress the importance of self-cultivation. Both Confucians and Taoists practiced self-cultivation as a means of optimizing existence.0 But what does this mean? What type of practices does self-cultivation entail? The Nei-yeh sheds light on these questions.

Inherent Ambiguity of Ancient Chinese Text

Before proceeding on a caveat:

This investigation is fraught with innate ambiguity for a variety of reasons. 1) The work is over 2000 years old. The meanings of words, ideograms and concepts have shifted over time. 2) The energy network that the Nei-yeh explores is complex. As mentioned, even Taoist works don’t interpret the key concepts in a consistent manner. Instead there is wide latitude of meaning associated with the terms, for instance the Tao. 3) The translation of Chinese into English is subject to the error due to cultural misunderstandings. This potential for error is compounded with ancient Chinese. Even scholars disagree as to the translation of key passages. 4) Commentators, even if they attempt to be objective, perceive meaning through their personal and cultural filters.

Harold Roth is the author of Original Tao, the first book that provides a complete translation and commentary on the Nei-yeh. He identifies his personal filter in the subtitle of his book - Inward Training and the Foundations of Taoist Mysticism. His commentary makes it quite clear that he interprets the Nei-yeh’s meaning through the filter of mysticism.

Written before there were self-identified Taoists and before the entry of Buddhism into China, this seminal work can be interpreted from a variety of arguably valid perspectives. Instead of attempting to be ‘true’ to the original meaning, which is shrouded in the uncertainty of both history and human bias, my intent is to convey an understanding of the Nei-yeh that is relevant to me as a musician, Tai Chi practitioner, and 21st century human being. I employ Journey to the West, Master Ni, and texts from Chinese alchemy to fine-tune the meaning of this important text. Reciprocally, the Nei-yeh provides both a philosophical framework and insight into these perspectives.

Nei-yeh's 26 Verses are Developmental

The Nei-yeh’s focus is upon maximizing the interactions of a holistic network of integrated, yet separable, energies and processes. The work identifies each of the key word-concepts and then offers suggestions as to how to best maximize their operations and interactions. Although loosely organized, the 26 verses, i.e. song-poems, seem to have an order. They can be read and studied randomly in similar fashion to the I Ching, the Chuang Tzu or even the Lao Tzu. However, the earlier verses of the Nei-yeh provide context for the later verses. Rather than isolated bits of wisdom, the song-poems appear to be developmental. The following exposition attempts to elucidate this order.

The first 4 verses set the stage by introducing some key concepts and some rudimentary, yet fundamental, relationships. Verse 1 speaks about jing, translated as ‘vital essence’ by Roth; Verse 2 highlights ch’i – ‘vital energy’; Verse 3 examines hsin – ‘mind’; and Verse 4 focuses upon the Tao, ‘the Way’. The relationships between these four word-concepts, i.e. jing, ch’i, hsin, and the Tao, are a central focus of the Nei-yeh.

Verse 1. Jing stored in the chests of Sages

- The vital essence (jing) of all things:

- It is this that brings them to life (shêng).

- It generates the 5 grains below

- And becomes the constellated stars above.

- When flowing amid the heavens and the earth

- We call it numinous (shên) and ghostly.

- When stored within the chests of humans,

- We call them Sages (sheng).1a

Verse 1 reports that jing is a generative force that brings things to life. It is the source of life/vitality (shêng). As a source of living vitality, jing is not merely mechanical energy. Still in the 21st century, Chinese medicine continues to associate jing with an individual's life force.

![]()

Lines 5 & 6: When jing flows between Heaven and Earth, it is called ‘numinous and ghostly’, i.e. heavenly and earthly spirits. These could be the spirits of Nature, such as hill and river spirits, or human ghosts, such as those that have died prematurely. Subtext: jing is more than the life force for biological creatures. It is also the animating force of the spirit world.

Lines 7 & 8: Those that have jing ‘stored in their chests’ are considered Sages. The chest is the location of the lungs and breath. As we shall see, ch’i is associated with the breath. This reading of the passage links jing and ch’i.

A more complete translation includes the highly significant ideogram for zhöng, i.e. center. Not just in the overall chest, jing is instead stored in the center (zhöng) of the chests of Sages. The chest’s biological center is the heart. Sages have jing stored in their heart. Due to this positive association, jing seems to be a cosmic energy source that we want inside our heart.

![]()

The verse poses an unspoken question. How do we get jing’s cosmic generative energy in the center of our chest and become a Sage?

The Ideogram for Sage (sheng)

Let us look at the ideogram that the Nei-yeh employs for Sage (sheng) to get a better notion of this important Chinese concept. The small box at the upper right signifies a mouth. The window-like structure at the upper left signifies ears or listening. The 3 horizontal lines with a vertical line through the center at the ideogram's bottom, signify a master or mastery.

The bottom component of the ideogram could also mean ruler or king. The top line of the three represents Heaven; the bottom line Earth; and the middle line the ruler. The vertical line that joins the three horizontal lines indicates that the ruler joins Heaven and Earth in the human realm. In other words, the master of this ideogram is an active participant in this world.

In prehistoric times, the king might have also been a shaman. As a shaman, he or she may have entered altered states of mind. Physical or mental practices might have catalyzed these transcendent states or it could have been due to ingesting organic substances, such as psychedelic mushrooms. These altered mental states presumably led to deep insights into the nature of reality that enabled the king/shaman to better lead his subjects.

The Nei-yeh delineates the types of practices, not the substances, that lead to this heightened understanding. This enlightened state is not permanent and is only the means to the goal of Sagehood.

Perceiving the ideogram holistically, the Sage is an individual who has mastered both speaking and listening. After listening carefully to the workings of the universe (because the ears come first), the Sage communicates his/her insights to others. Instead of a recluse that exclusively seeks personal enlightenment, the Sage is an individual that works for the good of humankind. Mystical states are only preliminary steps towards helping out.

Jing: Definitions & Ideogram

To gain a better understanding of jing, one of Nei-yeh’s mysterious cosmic energy sources, let us first examine a modern definition and then the ideogram.

From the Concise English-Chinese Dictionary, 1999, p. 233:

Jing I. 1. Refined; choice

2. perfect; excellent; of the best quality

3. meticulous; fine; precise

4. smart; bright; clever and capable

5. skilled; conversant; proficient

II. 1. energy; spirit

2. essence; extract

3. sperm; semen; seed

4. goblin; spirit; demon

It is evident that jing has many excellent connotations and some seem to be associated an individual’s character or abilities: for instance, refined, perfect, meticulous, smart, and skilled. Also associated with ethereal energy, jing is linked with spirits, goblins and demons.

Biologically, jing is sperm/semen, i.e. the seed of life. In this context, jing is frequently associated with our sexual energy, at least on the individual level. Extrapolating, jing becomes a universal generative force. Tantra has a similar emphasis on this generalized sexual energy. As an indication of the importance of the metaphor, many, if not most, tantric temples include a lingam and yoni in the center with the suggestion of ejaculation.

The original ideogram for jing, life force, had two parts. On top was the original symbol for shêng (vitality) that we discussed previously. It is the pictogram for a young sprout. Some of the connotations are: the beginning stages of life and natural generation. On the bottom was a pictogram for well. Taken together, the 2 symbols indicate that jing is the foundation of living vitality – the well-spring of life.

Jing’s modern ideogram has 3 parts. The 2 symbols on the right probably morphed from the original pictograms, i.e. shêng (vitality) and the well. Added later on, the radical on the left is the symbol for mi, uncooked rice. The rice symbol suggests that jing is associated with a universal energy source that nourishes human life.

Verse 2. Te + Awareness attracts Ch’i; Developing Te stabilizes Ch’i.

- Therefore this vital energy (ch'i) is:

- Bright! – as if ascending the heavens;

- Dark! – as if entering an abyss;

- Vast! – as if dwelling in an ocean;

- Lofty! – as if dwelling on a mountain peak.

- Therefore this vital energy (ch'i)

- Cannot be halted by force,

- Yet can be secured by inner power (te).

- Cannot be summoned by speech,

- Yet can be welcomed by awareness (yi).

- Reverently hold onto it:

- This is called "developing inner power (te)".

- When inner power (te) develops and wisdom emerges,

- The myriad things will, to the last one, be grasped.

Verse 2 addresses ch’i. This ‘vital energy’ is virtually everywhere, i.e. in both the vertical mountains and the horizontal ocean. Not just limited to living systems, heavenly spirits and earthly ghosts, as is jing, ch’i has a more universal component. While jing is associated with life’s sexual energy, ch’i is associated with breath, both individual and universal. Along with jing, ch’i is another cosmic energy source that we want to cultivate.

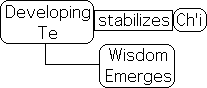

![]()

How do we tap into this abundant ch’i energy?

Although we want channel into ch’i’s universal energy, it can’t be halted by force nor can it be summoned by speech. Both force of arms and commands are helpless in evoking this elusive energy. It seems that ch’i cannot be called up consciously or directly.

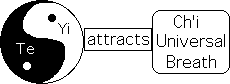

Instead the only way to channel ch’i power is to secure it with inner power (te) and welcome it with awareness (yi). It seems that we must employ 2 components to utilize ch’i – te and yi. Let us first examine te. Roth translates te as ‘inner power’.

![]()

What is this inner power, te?

It is sometimes translated as 'virtue'. This is the same te, as in the title of the Taoist classic – the Tao te Ching. Te is another key concept of the Nei-yeh.

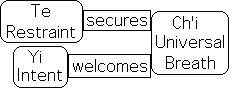

Once we have secured ch’i via te and welcomed it with awareness, we must hold onto it. This stabilizing process is known as ‘developing te’. As we develop te, wisdom emerges. This wisdom enables us to understand the workings of the cosmos.

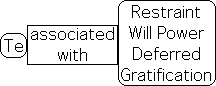

From this perspective, te is like a muscle that must be developed. As a mental muscle, te is associated with the related words – self-control, restraint and deferred gratification. In fact, te seems to be one of the primary mental muscles that we employ to corral the elusive forces of nature, such as ch’i, at least according to the Nei-yeh. Rather than succumb to the relatively automatic behavior of socio-genetic conditioning, we can choose to exercise te, our self-restraint muscle.

“The Nei-yeh – unlike the more familiar ‘Lao-Chuang‘ texts – states that one’s te is something that one must work on, each and every day. The practitioner must work to build up his/her te by practicing diligent self-control over all thought, emotion and action.”1

Welcomed by Awareness (Yi)

Let us now focus our attention upon the phrase ‘welcomed by awareness (yi)’.

What a curious phrase. It is as if we are greeting and inviting a friend into our home. ‘Welcoming’ certainly does not have the military connotations of force and commands. Further ‘welcoming’ implies the existence of something external. Rather than only our individual breath, ch’i could be considered the universal breath – the spirit that breathes life into the cosmos. We want to attract this spirit into our internal home – our spirit house. This is the first, but not the last time, that the Nei-yeh employs/implies the ‘spirit house’ metaphor.

How do we entice this cosmic energy source to come inside and stay awhile? Actively pursuing chi certainly does not work. In addition to securing it with te, we must also ‘welcome [ch’i] with awareness’.

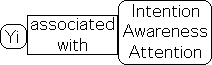

The character that Roth translates as ‘awareness’ in this phrase from line 10 is the Chinese word ‘yi’. This is a significant word-concept in the contemporary martial arts community. One text translates yi as “idea, intent, thought, content, purpose”2. Some implications could be ‘purposeful action’, ‘intentionality’ or simply ‘paying attention’.

Like te (restraint), yi also seems to be a mental muscle. As a complement to te, yi is associated with intention, awareness and/or attention.

In the context of this verse, we must pay attention, i.e. focus our intention, in order to attract ch’i to us. Validating this perspective, many Taoist texts exhort the practitioner to ‘be aware of the breath’, i.e. our personal ch’i. This attention (yi) could be passive, as in simply observing the breath, or active, as in ‘revolving the ch’i’.

To attract ch’i, we must exercise both mental muscles. ‘Te (inner power) secures’ and ‘yi (intent) welcomes’ this universal breath.

Complementary Muscles: Physical & Mental

Physical and mental muscles have many of the same features. While having a material essence, muscles are employed as part of a process. We employ them to manipulate our environment. They are meant to perform distinct functions. Similarly an instrument has physicality, but is meant to be played.

The more muscles are exercised the stronger they become. For instance, practicing the violin strengthens our musical muscles. Muscles also get exhausted and must be rested to replenish their strength. Finally muscles tend to be associated with a complementary muscle for balance. Each of these processes apply to both physical and mental muscles.

Te and yi are complementary mental muscles that are engaged to attract ch’i. This process is not simultaneous, but instead based in alternation – an alternating current (AC), rather than direct (DC). Further there is bit of each in the other that tends to moderate the extremes. For these reasons we have chosen the revolving yin-yang symbol to represent this process.

Directive, yi is linked with yang; restrictive, te is linked with yin. The alternation – contract and release – of these complementary mental muscles attracts ch’i.

Muscles have yet another significant feature. If a muscle is not exercised, it atrophies – looses strength. Regularly exercising our muscles is the only way to stay fit. This process applies to both physical and mental muscles.

Let us apply this understanding to the verse’s conclusion. Recall that ‘developing te’ stabilizes ch’i’s spirit energy after it enters our home. If ch’i is to stay awhile, we cannot be mental couch potatoes, but must instead regularly exercise the te-yi pair. (The Nei-yeh refines our understanding of both word/concepts – te and yi in subsequent verses.)

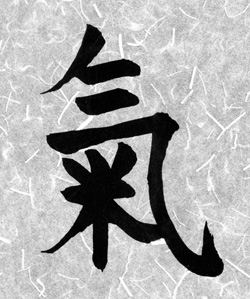

Ideogram for Ch’i

To gain a better understand of ch’i, the cosmic energy highlighted in this verse, let us examine its ideogram – shown below. On top is the symbol for ‘breath’. Below is the symbol for ‘uncooked rice’.

The character for rice, mï, has broad implications for the Chinese. Not merely an uncooked kernel, “the character shows a rice seedling complete with roots, leaves and grains.”3 This is a quintessential symbol for abundant fertility. Farmers can utilize the countless grains of rice to plant more rice fields. Once harvested and then cooked, rice can and does nourish the entire population of China. Further, it takes a stable agrarian population to tend the myriad fields of grain. Due to these many connotations, rice fields with their seedlings are at the base of Chinese civilization.

The character for breath also has significant connotations that extend far beyond the respiratory system. As an indication of its potency, the modern ideograms for both yin and yang include this same breath symbol in the exact same fashion as the ch’i ideogram. Instead of the rice ideogram, yang includes the sun symbol, while yin includes the moon symbol. Both are positioned beneath the symbol for breath. This parallel construction for the ideograms of the highly significant concepts, ch’i, yin and yang, suggests the importance of the breath symbol.

The combination of the potent symbols for rice and breath in the ideogram indicates that ch’i is more than just breath, as this verse illustrates. Connected with nutritive rice, the fundamental food source of China, ch’i is a universal energy that permeates and animates every aspect of the cosmos, not just living systems. The fact that the rice is in an uncooked state implies that ch’i is a raw form of energy that must be cooked before we can utilize its nutritive powers. The subsequent verses of the Nei-yeh indicate how to cook this raw energy in order to extract its beneficial essence. This is a key verse in that it articulates the processes by which we can secure and stabilize, thereby channel ch’i, the most universal of the cosmic energy sources.

Verse 3. Hsin naturally filled with vitality (shêng) & balance; Emotions disrupt natural perfection.

- All the forms of the mind (hsin)

- Are naturally infused and filled with it (vital essence/jing),

- Are naturally generated (shêng) and developed (because of) it.

- It is lost

- Inevitably because of sorrow, joy, happiness, anger, desire, and profit-seeking.

- If you are able to cast off sorrow, joy, happiness, anger, desire, and profit-seeking,

- Your mind will just revert to equanimity.

- The true condition of the mind

- Is that it finds calmness beneficial and, by it, attains repose.

- Do not disturb it, do not disrupt it

- And harmony will naturally develop.

Verse 3 focuses upon hsin, another key concept in Chinese thought, past and present. Hsin is most commonly translated as ‘heart-mind’.

The first 4 lines have some inherent ambiguity associated with them due to the word ‘it’. What does the word ‘it’ refer to? Roth assumes that ‘it’ refers to ‘vital essence/jing’. In other words, ‘the mind’s forms are infused with jing, the source of vitality. Jing is lost when…’ This reading is certainly plausible in terms of the context of later verses and traditional associations.

The hazard of historical assumptions is that they have the potential to distort meaning. As mentioned in the introductory chapter, the NY employs many of Taoism’s traditional concepts in a different way than other Taoist classics, for instance the Tao Te Ching. As such, we attempt to resist traditional Taoist associations until the Nei-yeh makes the connections.

The initial verses have only hinted at the relationship between jing and hsin. Although a significant element in the 1st verse and later verses, this verse does not include the ideogram for jing. It focuses primarily on the innate nature of hsin.

Our developmental perspective suggests another translation of these verses.

“1. The forms [patternings] of the mind (hsin)

2 & 3.

Are naturally infused and filled with vitality (shêng) and generative energy.

4.

It [this natural state of vitality] is lost when …”

Lines 2 &3 employ a parallel construction that employs the ideogram for ‘natural’ 4 times. Due to this pattern, we infer that the ‘it’ in line 4 refers to mind’s natural state. Abbreviating for clarity, the mind (hsin) is naturally filled vitality (shêng).

![]()

Subsequent lines describe the mind’s fall from this original purity. Hsin, our heart-mind, loses its natural perfection due to emotions and desires, both positive and negative. Another culprit is ‘profit-seeking’, the last character of lines 5 & 6. The ideogram can also be translated as ‘taking advantage of others’, perhaps for power or money. The craving to advance one’s position at the expense of others also disrupts mind’s natural vitality.

![]()

If we can but cast off these disruptive emotions, our heart-mind ‘naturally’ returns to its balanced state of repose, i.e. harmony. Line 9 employs the same character for ‘taking advantage’. Rather than ‘taking advantage of others’ as in lines 5 and 6, which leads to mental turbulence, we ‘take advantage’ of calmness in order to attain mental equilibrium.

![]()

'Natural’ is a key word in the Nei-yeh. An underlying assumption seems to be that mind’s ‘natural’ state is good but is corrupted by disruptive emotions. If we can but cast off these emotions, we ‘naturally’ return to our original state of purity.

The unspoken question from this verse: How do we rid ourselves of the emotional disruptions that disrupt the ‘natural’ vitality of hsin, our mind?

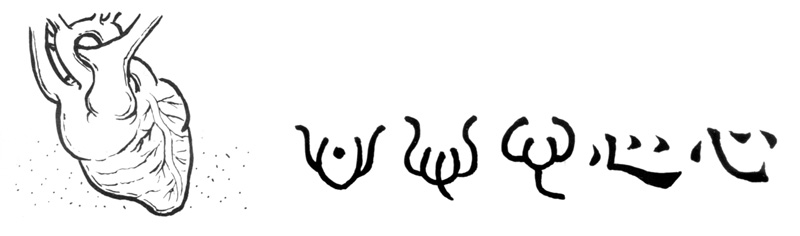

Hsin: the Ideogram

Although hsin is frequently translated as ‘mind’, it is associated with our heart, rather than our brain. In order to provide the proper connotations, a traditional translation of hsin is ‘heart-mind’. Below is the ideogram for hsin.

The ideogram developed from a rough rendition of the lobes of the biological heart.

While the pictogram derived from a static thing – a material heart, hsin represents a dynamic process. Most of the Nei-yeh’s most significant word-concepts are also processes, rather than things. Due to its connection to the processes of the heart-mind, hsin is associated with both our emotions and our thoughts. Under this schema, our emotions and thoughts compose an intertwined, perhaps inseparable, network. Further our emotional mind goes through an infinite number of transformations - changing nearly instantly from one feeling to another, sometimes due to a mere smile or frown.

As an indication of its importance, this ideogram appears as a component of countless ideograms.

Verses 1>3: Summary

Summarizing verses 1 >3 to aid retention:

V1) Jing is the source of life/vitality (shêng). Sages have jing in the center (zhöng) of their chests. On the individual level, jing is traditionally associated with sexual energy.

V2) Ch’i is a pervasive, powerful, yet elusive, cosmic energy. On the individual level, ch’i is traditionally associated with breath and blood flow. To attract ch’i, we must employ the complementary mental muscles – te (restraint) and yi (intent).

However simply attracting ch’i is not enough, as it might leave suddenly. We must stabilize this important energy source. ‘Developing te’, inner power, stabilizes ch’i. Wisdom naturally emerges from this developmental process.

It is evident that we want to cultivate the energies of both jing and ch’i as they bring Sagehood and wisdom.

V3) Hsin, our heart mind, is naturally filled with vitality (shêng) and balance. Emotions disrupt this natural perfection. If disruptive emotions are eliminated, hsin naturally returns to perfection.

These verses introduce many unanswered questions. How do we get jing in the center of our chest? What does it mean to ‘develop te’? And how do we eliminate the disruptive emotions that upset hsin’s natural perfection? As an indication of the NY’s developmental nature, the ensuing verses address these questions.

Footnotes

0 Taoism, the enduring tradition, Russell Kirkland, Routledge, 2004, p.xviii

1a Harold Roth, Original Tao, Inward Training (Nei-yeh), Columbia University Press, 1999, p. 46. The translations of the Nei-yeh's verses comes from Roth’s book. To elucidate the test, I include Chinese words in brackets.

1 Russell Kirkland, Taoism, the enduring tradition, Routledge, 2004, p. 46

2 Chinese for the Martial Arts, Carol M. Derrickson, Charles E. Tuttle Company, Rutland, Vermont & Tokyo, Japan, 1996, p. 19

3 Chinese Calligraphy, Edoardo Fazzioli, Rebecca Hon Ko, Abbeville Press, 1986, p.198