3. Nei-yeh 4>6: Tao & Te

- Verse 4. Tao: we use of its Te daily; Tao stops within us, then leaves inexplicably.

- Tao, the Ideogram

- Te, the Ideogram

- Tao: Both Ideal Practices & Mystical State

- Te & Contemporary Science

- Verse 5. Tao resides in excellent hsin = tranquil hsin + regular ch’i. To attract the Tao, cultivate hsin by making thoughts tranquil.

- Yi: the Mentation Complex

- I Ching: Applying will to thoughts, like applying discipline in a Family

- Yi, the Ideogram

- Verse 6. Tao employed to cultivate hsin and align body. Without vitality (shêng) we die and fail,; with it we succeed and flourish.

- Shêng (Vitality): Ideogram

Introduction

The first 3 verses of the Nei-yeh provide an introduction to jing, chi, and hsin. These are 3 of the key word-concepts of the influential Chinese behavioral technology that underlie this ancient Chinese text. The Nei-yeh's following 3 verses focus upon the Tao. The first verse articulates some of the characteristics of the Tao.

Verse 4. Tao: we make use of its Te daily; Tao stops within us, then leaves inexplicably.

- Clear! as though right by your side.

- Vague! as though it will not be attained.

- Indiscernible! as though beyond the limitless.

- The test of this (Tao) is not far off.

- Daily we make use of its inner power (te).

- The Way (Tao) is what infuses the body.

- Yet people are not able to fix it in place.

- It goes forth but does not return,

- It comes back but does not stay [in its lodging place (shê)].

- Silent! none can hear its sound.

- Suddenly stopping! it abides within the mind (hsin).

- Obscure! we do not see its form.

- Surging forth! it (shêng) arises with us.

- We do not see its form,

- We do not hear its sound,

- Yet we can perceive an order to its accomplishments.

- We call it "the Way (Tao)".0

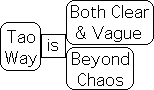

Verse 4 highlights some innate features of the Tao. The Tao is both elusive and unnamable. It suddenly stops within us, but then leaves just as inexplicably. This departure is because the Tao has no place to abide.

Line 5: "Daily we make use of the Tao's inner power (te)." This is the first verse that links Tao and te, but not the last. The original name for Taoism was Tao-te Chia – the School of the Way and its Power.1

There are 2 interpretations of this relationship. A traditional perspective holds that this inner power arises when the Tao is present. This interpretation implies that the Tao is some kind of entity or special state of being.

The Tao can also be perceived as the ideal Way or method of being. Under this perspective, this line can be interpreted as: If we are on the Path, i.e. following the ideal practices – the Tao, then we will employ te, our self-restraint muscle, on a daily level.

![]()

If we pursue these daily practices, the Tao, as the ideal behavior pattern, will stabilize within us. In other words, the probability that we will follow the Way will increase until it becomes an ingrained habit. As an example, establishing a regular exercise regime has a momentum that makes it easier to practice.

Lines 14-17: Although our senses cannot hear or see it, we can perceive an order to the Tao’s accomplishments – presumably its effects upon our lives and the world around us.

Tao, the Ideogram

Due to the importance of the Tao in the Nei-yeh, let us examine its ideogram to better understand its flavor. Following is the Tao's ideogram.

On the bottom is the symbol for foot. As the foot seems to be walking, it frequently signifies a journey - a process. The inner pictogram, the one that is surrounded as a whole by the radical for journey, is the ideogram for shöu. In the Chinese/English Dictionary cited above, shöu is translated as: 1) head; 2) leader, head, chief.

Shöu’s pictogram derived from a horned animal, perhaps with antlers. Perhaps a shaman/leader wore a horned headdress to tap into the animal’s raw energy. In ancient times, the ideogram came to signify a general, complete with two antler/plumes, at least according to some sources. Regardless of origin, the ideogram for Tao suggests a path of authority – of someone that is in control. The military nature of the leader suggests that it requires discipline and guidance to remain on the Path.

=

=  +

+

Tao = Journey + Leader

The Nei-yeh employs the word-concept Tao in this manner. As we shall see, the verses regularly suggest that we consistently employ the complementary mental muscles – te (restraint) & yi (intent) – to prevent drifting off course.

The inner ideogram has three parts.

=

=  +

+  +

+

Leader = 8 directions + Man + Eye

The bottom represents the eye; the middle two lines are the symbol for human or man; while the top two antenna looking protuberances are the radical for the number eight. Many times eight represents the eight directions, the primary directions, forward, backward, left, right, and the four diagonals. Hence the eight directions are representative of everywhere. The leader or head looks everywhere and sees everything. This leader observes, but does not speak. Sometimes simply paying attention is enough to keep people on track. Roughly speaking, the whole ideogram for the Tao suggests a journey that is led by a general or chieftain, who sees everything.

Tao as load-head, magnetic attractor

The ancient Chinese employed a component of the character "tao" to indicate the (load)head. Understood as the metallic lode that functions as a magnet for the compass "needle," the load-head creates a course to be followed. The lodestone sees, but does not speak. These characteristics are totally in line with the ideogram's pictorial meaning.

For many, the Tao has mystical or even supernatural connotations. To see what it means for the Chinese reading this symbol, let us look at a Chinese/English dictionary. The Concise Chinese English Dictionary provides us with these definitions:

dào: (as a noun)

1) road, way, path.

2) line.

3) way, method.

4) doctrine, principle

5) Taoism, Taoist

The same ideogram for tao simultaneously means method, purpose, path, doctrine and Taoist. The context of the use determines the emphasis, but does not eliminate the other meanings. The Chinese are specialists in ‘both/and’ reasoning, rather than the Western ‘either/or’ mentality. Tao means both path and Taoist, not one or the other.2c However, the definitions don’t seem to include the mystical connotations that are commonly associated with the Tao. In this sense, the Tao could be any method, process or way, not only a mystical path. For instance, understanding the tao of chickens enables me to better take care of and understand the needs of my small flock.

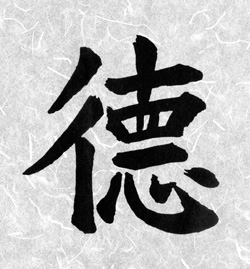

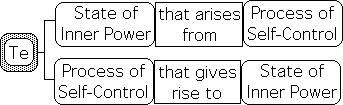

Te, the Ideogram

As mentioned Tao and te are frequently linked. This linkage occurs in both the Nei-yeh and the title of the Taoist classic, the Tao Te Ching. Let's examine the ideogram for te to better understand the connection. On the left is a simplified symbol for a 'foot'; on the upper right is the modified character for ‘straight or upright’; and on the lower right is the symbol signifying 'heart' (hsin).

One meaning could be: follow the path of an upright heart, perhaps our innate nature. The Chinese, Taoists in particular, believe that we are born pure and then corrupted in the process of growing up. Through self-cultivation practices, we attempt to return to te, our natural virtue.

In contrast to the traditional meaning that 'virtue' is innate, fixed and determined from birth, the Nei-yeh regularly implies that we strengthen te by exercising self-restraint. Further it is possible to interpret hsin, our heart-mind, to mean our innate inclinations, including our emotional tendencies. The "(foot) stepping" radical here is different than the "walking (foot)" radical in Tao. Rather than a journey, it suggests steps towards a goal – as with the Tao, an ongoing process rather than a fixed state.

Under this perspective, the ideogram suggests that te is the process of rectifying hsin in order to shape and regulate our innate tendencies. This shaping could include engaging in self-cultivation practices rather than becoming a victim of our emotions and desires. Te is the action, i.e. daily practices, of aligning hsin, i.e. making the heart-mind upright.

Both Tao and te include radicals that indicate an ongoing process rather than a state of being. Tao, as the Way of ideal self-cultivation practices, includes regularly exercising te, our self-restraint muscle, to shape our innate tendencies, hsin, in order to remain on the Path.

For fun, let’s take this journey yet one more step. According to the traditional view, te is an innate state that is developed through acts of cultivation etc. The inner power (te) developed in this fashion could be likened to charisma. The power of the person’s aura automatically harmonizes the surrounding world. The individual who possesses this charisma orders the world without doing anything (the essence of the essence of the Taoist concept of wu-wei, non-action within action).

Could te be both an innate state and a process? If so, the te process of restraint contributes to the te state of inner power. Te both enables and is enabled by the Journey of being on course, Tao. From this perspective, te is both the state of ‘inner power’ that arises from the process of self-control and the process of self-control that gives rise to the state of inner power/charism.

In such a way, even state and process circle each other, like the black and white fish in the yin-yang symbol. The black and white eyes of the two fish signify the interactive feedback between process and state. State exerts an influence on process and vice-versa. This interactive 2-way feedback loop negates/neutralizes cause and effect. This innate feature of living systems transcends the linear logic that characterizes matter so perfectly. This interactive feedback indicates that living systems consist of more than just matter. The Nei-yeh, as well as Chinese thought in general, supports this perspective.

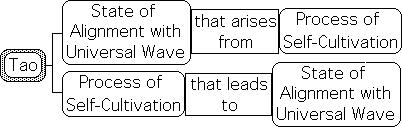

Tao: Both Ideal Practices & Mystical State

The same analysis applies to the Tao. It is both the ideal self-cultivation method/process and the enlightened state of alignment with the Universal Wave, i.e. attuned to cosmic principles (li).

As ‘way or method’, the Tao could represent the ideal practices that put an individual onto the Path that presumably leads to Sagehood. Indeed Tao is frequently translated as ‘the Way’, not ‘a way’. One purpose of the Nei-yeh is to reveal the general self-cultivation practices that both take us to and keep us on the Path.

While the Tao represents the method to attain Sagehood, the Sage is also aligned with the Tao, i.e. in midst of the Universal Flow. In this context, the Tao could mean the state of perfect balance and/or an exalted, altered state of consciousness, for instance a mystical or inspired state of consciousness.

In contrast to the Western vocabulary, the Chinese language embraces a fungible approach to words. As such, the meanings of Chinese word-concepts tend to be ‘both-and’ rather than ‘either-or’. For instance, ch’i is both breath/blood circulation and a cosmic energy source that permeates the universe. Jing is both our individual sexual energy and the universal source of life. Similarly the Tao can mean both the ideal self-cultivation practices, the Path, the Way, and alignment with the mystical Flow. The Nei-yeh employs the Tao in each of these fashions. The Nei-yeh employs the Tao in each of these fashions.

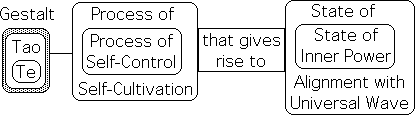

Tao and te form a gestalt (a fully integrated, yet separable, network). Te’s process of self-control is a feature of the Tao’s ideal self cultivation practices that lead to te’s inner power that accompanies alignment with the Tao’s Universal Wave.

Te & Contemporary Science

How do we make sense of the Chinese word-concept ‘te’ from a 21st century scientific perspective? Te’s associative words, i.e. ‘charisma’, ‘inner power’, ‘constelling force’, ‘emanating from the center’, ‘ordering the world without acting’, seem to be too mystical or nebulous to be studied from a scientific perspective. What possible contemporary psycho-physiological counterpart could there possibly be that mirrors the ‘inner power’ associated with ‘te’?

Cognitive scientists have begun exploring a human trait deemed ‘deferred gratification’. This trait is associated with a successful life in terms of career, finances, emotional regulation, and relationships.

Studies have also shown that this virtue shows up very early in infancy. Some think that it is genetic, i.e. innate. Others believe that it can be developed to some extent. Indeed one of the tasks of parenting is to exercise, thereby develop, this mental muscle in their offspring. Discipline is primarily administered to train children to both refrain from performing some kind of inappropriate behavior and to direct them towards more constructive activities.

These psychological studies fit neatly with the ancient belief system of the Chinese ruling class. It also dovetails with our notion that te is a mental muscle associated with self-restraint. ‘Deferred gratification’ like ‘te’ can be developed through use. Further this mental muscle from the 2 systems is associated with success or the inner power that leads to success.

We mentioned that the Nei-yeh presents a testable behavioral technology that is relevant to 21st century humans. Te’s state of ‘inner power’ could be defined and studied in terms of a ‘successful life’. Te’s process of ‘self-control’ could be likened to contemporary science’s ‘deferred gratification’ muscle. The Nei-yeh states the exercising self-control leads to inner power. 21st century experiments have shown that the ability to exercise ‘deferred gratification’ is positively correlated with a ‘successful life’. At least in this way, it seems that the Nei-yeh and contemporary psychology have isomorphic structures, in the sense that they have parallel cognitive constructs that are associated with parallel results.

Verse 5. Tao resides in excellent hsin = tranquil hsin + regular ch’i. To attract the Tao, cultivate hsin by making thoughts tranquil.

- The Way (Tao) has no fixed position;

- It resides in the excellent mind (hsin).

- When the mind is tranquil and the vital energy (ch'i = breath) is regular,

- The Way can thereby be halted.

- That Way is not distant from us;

- When people attain it they are sustained.

- That Way is not separated from us;

- When people accord with it they are harmonious.

- Therefore: Concentrated! as if you could be roped together with it.

- Indiscernible! as beyond all locations.

- The true state of the Way

- How could it be conceived of or pronounced upon?

- Cultivate your mind by making your thoughts tranquil,

- And the Way can thereby be attained.

Verse 5 articulates some additional features of the Tao: its advantages, where it resides, and how to keep it there. The Tao resides in an excellent heart-mind (hsin). Hsin can be viewed as our personal behavior patterns. If we are able to remain on the Path, i.e. maintain the correct self-cultivation practices, our hsin is excellent.

![]()

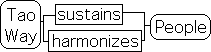

The Tao, as the ideal self-cultivation practices, both sustains and harmonizes those who follow this Path.

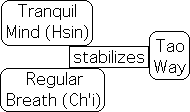

Hsin is excellent when it is tranquil (ching), presumably undisturbed by disruptive emotions (V3). Further our ch’i must be regular. Ch’i is also associated with our breathing and blood flow, i.e. oxygenation of the body. This precondition for an excellent mind probably refers to breath control.

Connecting some dots: a tranquil mind and regular breathing generates the excellent mind, in which the Tao resides (from line 1).

By ‘developing te’, our inner power, we are able to stabilize our breath, ch’i (V2). Regular breathing, ch’i, is a prerequisite for the excellent hsin that is a prerequisite for attracting the Tao. Alternately, by practicing breath control, we strengthen te, the mental muscle that we employ to keep us on the Path.

The verse finishes by stating we can attain the Tao by cultivating hsin and making our thoughts tranquil, i.e. no disruptive emotions. Seemingly these 2 conditions are connected. It seems safe to say that calming our thoughts is equivalent to mental cultivation. Could it be that te is the mental muscle that we employ to calm our thoughts?

![]()

Yi: the Mentation Complex

Both line 12 and 13 contain the ideogram for yi. Recall that yi can mean, ‘will’, ‘intent’ or ‘intentionality’. Here it appears with a different, though related, meaning. Due to context, Roth translates it as ’conceive upon’ or simply ‘thoughts’, i.e. thinking.

To emphasize the parallel structure, these lines could be translated: “Avoid thinking (yi) or speaking about the true state of the Tao/Way. Instead cultivate hsin/heart-mind by calming thoughts (yi) to attain the Tao/Way.” Why should we avoid thinking about the ‘true state’ of the Tao? Could this be because the Tao does not have a true, i.e. fixed state, but is instead a dynamic wave that rises and falls?

Why should we calm our thoughts rather than attempting to understand the true state of the Tao? Line 3 from the same verse provides a clue: 'Calming the mind/hsin and regulating the breath/ch’i also attracts the Tao’. Combining the two: Calming the thoughts/yi also calms the mind/hsin.

By what mechanism do we calm hsin? We can easily imagine that the te/yi synergy operates in a complementary fashion to achieve inner tranquility. Te is employed to restrain ‘thoughts/thinking’ from drifting in an unproductive direction, i.e. ‘attempting to understand the true nature of the Tao’. Yi is employed to direct our attention/yi in a more productive direction, i.e. towards calming our thoughts/yi and regulating our breath/ch’i.

Understood from this perspective, yi is simultaneously attention, will, and thoughts. To gain control of our thoughts (yi), we employ our will (yi) to direct our attention (yi) towards tranquility. In a later verse, yi is associated with our non-verbal thoughts – pre-verbal mentation. As a gestalt, yi could be conceptualized as a preverbal thinking complex that includes thoughts, will and awareness in one package.

Viewed as a complementary mental muscle group, this yi complex can go feral if not guided properly. Like children, the mentation synergy tends to spiral out of control without proper guidance. Left to their own devices, our innate or learned cognitive processes might multiple example upon example of perceived injustices. These inflaming examples provide the ideational fuel that sustains negative or arousing emotions. Instead of allowing this negative process to achieve any momentum, especially bio-chemical, we employ yi to curb, shape and guide our thoughts towards tranquility. With each repetition of this process, the probability of negative behavior decreases and vice versa. This is the process of cultivating hsin/mind.

I Ching: Applying will to thoughts, like applying discipline in a Family

The I Ching refines our understanding of runaway thoughts. The hexagram for Family consists of the Fire Trigram at the base and the Wind Trigram on top. The third line from the bottom is a Yang line. Due to its position, i.e. the top of the Fire Trigram, this yang line represents applying discipline to harmonize the family.

When this yang line is imbalanced, i.e. reaches its limit, the I Ching provides an ancient song-poem that is applicable.

“If the Family is run with ruthless severity, tempers flare up.

Remorse is the consequence.

Good Fortune nonetheless.

If women and children are too frivolous,

Humiliation is the consequence.”

Paraphrasing: Although too much discipline results in ‘remorse’, this is better than too much leniency, which results in ‘humiliation’.

The I Ching’s verbiage has distinctly patriarchal overtones. If the patriarch of the clan does not exert enough discipline, then women and children will engage in frivolous behavior that leads to humiliation. The implicit message: To avoid embarrassment for the family, the father must be strict.

Liu I-Ming, an 18th century follower of Taoism’s Inner Alchemy, provides a more egalitarian message to this passage from the I Ching. He likens the process to self-cultivation. In his commentary, the family consists of our many selves, i.e. the variety of components that comprise our psyche. We might rebel against the strict discipline, perhaps a tight regimen that we impose upon our selves, especially our thoughts. Better too strict than too lenient with our inclinations.

“Otherwise, there are thoughts that do not leave and one becomes lazy and tricky, indulging in feelings and desires. How can one reach selflessness? Those who practice in this way never attain the Tao; they only get humiliation. This indicates the need for firmness in refining the self.”1b

In similar fashion, we must apply the te/ye synergy – restraint and direction, else our thoughts will become too ‘frivolous’, i.e. indulgent. Indulging our thoughts and feelings leads to ‘humiliation’, i.e. biochemical feedback that disrupts our tranquility. This imbalanced psycho-physiological state erodes cognitive skills and physical vitality. Better to err on the side of too much discipline than not enough.

In this particular verse, the Nei-yeh counsels us to exercise the te/yi synergy to both calm our thoughts and refrain from fruitless speculation on the Tao. If we are too lenient, the mental muscle group atrophies. With no strength to guide and restrain our thoughts, runaway emotions disturb our mental tranquility, which repels the Tao. Conversely if we employ yi/will to guide our yi/thoughts towards quietude, this attracts the Tao.

Yi, the Ideogram

Sometimes ideograms evolve. Other times they are consciously constructed. As examples, intentionality, as well as evolution, provided the modern ideograms for yin, yang, ch’i, and Sage. Let us examine the ideogram for yi under the assumption that it had an element of consciousness in its construction.

The ideograms for te and yi have a parallel construction. Both ideograms include hsin, the heart-mind symbol, at their base. This is yet another indication of their complementary nature.

At the top of yi’s ideogram is the symbol for li, which means ‘to stand upright’. The ideogram for li derived from the pictogram of a man standing planted upon the ground2a with his legs spread apart in a position of authority – someone who is in control of himself and his world2aa. When the ideograms for li and cheng (alignment) are combined it is the military command, ‘Stand Attention!’

In the middle of yi’s ideogram is the sun symbol2b. When the sun symbol is above the upright symbol, it means day. Here the relationship is reversed. One implied nuance of yi’s ideogram could be that we must apply the sun’s direct awareness to align our emotional state. Another implication: we must shine our intent upon body alignment and that this process will simultaneously align hsin, our heart-mind.

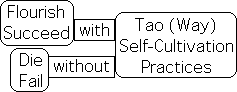

Verse 6. Tao employed to cultivate hsin and align body. Without vitality (shêng), we die and fail; with it, we succeed and flourish.

- As for the Way (Tao):

- It is what the mouth cannot speak of,

- The eyes cannot see,

- And the ears cannot hear.

- It is that with which we cultivate the mind and align the body.

- When people lose it (vitality = shêng) they die;

- When people gain it (shêng) they flourish.

- When endeavors lose it (shêng) they fail;

- When they gain it, they succeed.

- The Way never has roots or trunk;

- It never has leaves or flowers.

- The myriad things are generated (shêng) by it.

- The myriad things are completed by it.

- We designate it "the Way" (Tao).

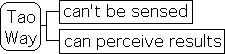

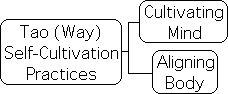

Verse 6 continues on the topic of the Tao. The song-poem reiterates some themes from Verse 4. Although the Tao can’t be sensed, we employ the Tao to cultivate hsin, our heart-mind, and align (cheng) our body. This is the first time that body alignment is mentioned, but not the last. Could it be that we employ the Tao’s inner power, te, to cultivate our mind and align our body?

Line 5-8: Without vitality (shêng), we die and our endeavors are doomed to failure. With vitality (shêng), we flourish and succeed.

Lines 12-14: The Tao generates and completes the myriad things.

If we are on the Path, i.e. cultivating both mind and body, this optimizes our vitality (shêng), which enables us to generate and complete our myriad projects.

![]()

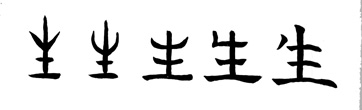

Shêng (Vitality): Ideogram

Already in these first 6 verses, the ideogram for vitality (shêng) is frequently employed. It is significant concept of Nei-yeh. In fact, shêng appears 20 times – as many times as the Tao and more than any other ideogram except hsin. Could shêng be the primary goal of inner cultivation?

Let us trace its development as an ideogram to get a better notion of its flavor. It began as a small plant (signified by a vertical line with a upward leaf-like curve on both sides) that is growing from the ground (signified by a horizontal line). The entire image suggests a sprout. To indicate that the plant was continuing to grow, another horizontal line was added between the sprout at the top and the ground at the bottom. This growing plant eventually became the ideogram for vitality.3

With this image in mind, we can better understand shêng’s dictionary definitions. ‘shêng: giving birth to, generate, grow, sprout, light (a fire), living, existence, emotion, life, livelihood’. Associated with initial growth, not flowers or fruit, shêng can also mean ‘unripe, green or raw’4 or ‘unusual, unripe, unpolished’.6 In other words, the vitality has not come to fruition. Its raw potentials are vast.

This nuance has a significant implication. The vitality that emerges due to self-cultivation is undirected and unrefined. The Nei-yeh does not prescribe any particular course of behavior for this internal energy, for instance kind, generous, ambitious, or inspired. Each human, whether artist, musician, mother, politician, athlete or warrior, can manifest this inner vitality (shêng) in any way that seems appropriate.

Verses 4 >6: Summary

Summarizing verses 4 >6 to aid retention:

V4) We use the Tao’s te on a daily level. The Tao comes and then departs. Although we can’t sense the Tao, we can perceive its effects.

V5) The Tao abides in an excellent hsin. It sustains and harmonizes those with an excellent hsin. Hsin is excellent when it is tranquil (ching) and ch’i (breath) is regular. By cultivating hsin, i.e. making our thoughts tranquil, the Tao is stabilized. Rather than being transient, the Tao abides within our center (zhöng).

V6) We employ the Tao (presumably its te) to both cultivate hsin and align (cheng) our body. The Tao is the source of generation (shêng) and completion. We are doomed without the Tao’s vitality (shêng). Conversely, we flourish and succeed when shêng is present.

Footnotes

0 Harold Roth, Original Tao, Inward Training (Nei-yeh), Columbia University Press, 1999, p. 46. The translations of the Nei-yeh's verses comes from Roth’s book. To elucidate the test, I include Chinese words in brackets.

1 Barbara Aria & Russell Eng Gon, The Spirit of the Chinese Character, Chronicle Books. San Francisco, 1992, p.20

2 The Spirit of the Chinese Character, p.20. This book supplies many of the ideograms and analysis for this series of articles on the Nei-yeh.

1b Taoist I Ching, Liu I Ming, translated by Thomas Cleary, Shambala Publications, 1986, p. 144

2a Chinese Characters, Dr. L. Wieger, S. J., Dover Publications, first published 1915, this edition 1965, p.157, Lesson 60H

2aa Chinese Calligraphy, Edoardo Fazzioli, Rebecca Hon Ko, p.68

2b Weiger, p.311, Lesson 143A

2c The ‘both-and’, ‘multiple meanings’ feature of the Chinese language makes their poetry particularly difficult, if not impossible, to convey in European languages.

3 Chinese Characters, Dr. L. Wieger, S. J., Dover Publications, first published 1915, this edition 1965, p. 203

4 Concise English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 397

5 Chinese Calligraphy, Edoardo Fazzioli, Rebecca Hon Ko, Abbeville Press, 1986, p. 52

6 Chinese Characters, Dr. L. Wieger, S. J., Dover Publications, original 1915, 1965, p. 638