Nei-yeh (Chinese Self-Cultivation Manual)

Verse 21. Human Life: Harmonizing Jing & Body => Vitality & Longevity

1 As for the life (shêng) of all human beings,

2 Heaven brings forth their vital essence (jing).

3 Earth brings forth their bodies.

4 The two combine to make a person.

5 When they are in harmony there is vitality (shêng).

6 When they not are in harmony there is no vitality (shêng).

7 If we examine the Way (Tao) of harmonizing them,

8 Its essentials are not visible;

9 Its signs are not numerous.

10 Just let a balanced and aligned [breathing] fill your chest

11 And it will swirl and blend within your mind (hsin).

12 This confers longevity.

13 When joy and anger are not limited,

14 You should make a plan [to limit them].

15 Restrict the five sense-desires;

16 Cast away the dual misfortunes

17 Be not joyous, be not angry,

18 Just let a balanced and aligned [breathing] fill your chest.

Commentary

Human Life is the focus of Verse 21.

Lines 1-4:

1 As for the life (shêng) of all human beings,

2 Heaven brings forth their vital essence (jing).

3 Earth brings forth their bodies.

4 The two combine to make a person.

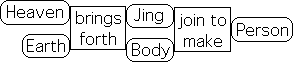

What generates Human Life? China's Heaven/Earth/Human construct answers the question. Heaven supplies jing (life force) and Earth supplies the body. These two, i.e. generative energy and material substance, combine to make a person.

The ideogram for life in this verse is shêng, a word that Roth sometimes translates as vitality. In earlier verses, for instance Verse 8, Roth conflates jing and shêng, almost treating them as synonyms. This verse makes it clear that shêng (life/vitality) is instead a combination of heavenly jing and the earthly body. Put in scientific terms, life (shêng) is a combination of matter (body) and energy (jing).

The ideogram for body can also be translated as form. In this context, jing is formless energy, while the human body is form without energy. Shêng (vitality or life) is the combination of form and energy (jing).

Form in this verse can be thought of as the human body, with all its parts. Form can also be insubstantial, for instance the sonata form in music or the Tai chi form in the martial arts. In both cases, these forms must be infused with jing (energy) in order to have any meaning. This discussion suggests that shêng is connected with a person, while jing is pure energy.

Lines 5-6:

5 When they are in harmony there is vitality (shêng).

6 When they not are in harmony there is no vitality (shêng).

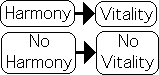

When these essences, i.e. jing and the body, are in harmony, there is personal vitality (shêng) and vice versa. As evidence of the continuity of beliefs espoused by the Nei-yeh, traditional Chinese medicine continues to hold this perspective in the 21st century.

Lines 7-12:

7 If we examine the Way (Tao) of harmonizing them,

8 Its essentials are not visible;

9 Its signs are not numerous.

10 Just let a balanced and aligned [breathing] fill your chest

11 And it will swirl and blend within your mind (hsin).

12 This confers longevity.

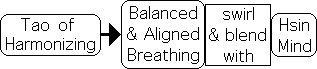

What is the Tao, the Way, of harmonizing jing and body? The essentials are not visible and the signs are not numerous. The key is balanced and aligned breathing, at least according to Roth. Proper breathing will presumably ‘swirl and blend’ with the mind (hsin) to confer longevity.

Note that Roth inserts ‘breathing’ in brackets, indicating that this is his interpretation. While plausible, there is no reference to breathing in the text. Although the lungs are in the chest, which suggests breathing, the heart, which is associated with hsin, is the center of the chest. Perhaps the song-poem references the chest to include both breath from the lungs and emotions from the heart. In this case, harmonizing includes balancing and aligning both ch’i and hsin – the breath and our thought/emotions.

What is the difference balancing and aligning? For the Chinese, ‘balance’ implies horizontal while 'alignment' implies vertical, i.e. upright. In other words, the tempering process encompasses all directions.

The ideograms for ‘swirl and blend’ in line 11 can also be translated as ‘reason and control’. With these alternatives in mind, we suggest another possible translation.

7 Examining the harmonizing Way (Tao):

10 Balancing and aligning filling the chest;

11 Reasoning and controlling hsin;

12 These [practices] confer longevity.

What does ‘reasoning and controlling hsin’ mean? One interpretation could be ‘analyzing and controlling hsin’s thoughts and emotions’. We must presumably engage in a careful analysis of motivations in order to mitigate destructive behavior patterns.

Under this perspective, the harmonizing path includes two processes – 1) balancing and aligning ch’i (our breath) and 2) analyzing and controlling hsin (our thoughts and emotions). This path presumably harmonizes jing and the body, which results in vitality and longevity.

Lines 13-18:

13 When joy and anger are not limited,

14 You should make a plan [to limit them].

15 Restrict the five sense-desires;

16 Cast away the dual misfortunes

17 Be not joyous, be not angry,

18 Just let a balanced and aligned [breathing] fill your chest.

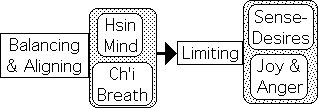

These lines specify some roots of imbalanced behavior. It is also important to both cast away the ‘dual misfortunes’ of joy and anger and restrict the sense-desires. Instead of directly addressing these problems, the Nei-yeh suggests that we merely redirect the focus of our attention. Just focus upon balancing and aligning (cheng) perhaps both breathing (ch’i) and the mind (hsin). (As an indication of the importance of this suggestion, it occurs twice in this verse, both in lines 10 and 18.) This redirection of focus presumably has the effect of mitigating excessive desires and emotions.

Evidently both sensual cravings and excessive emotions, positive and negative, undermine the jing/body balance that is a foundation of vitality. By focusing upon balancing/aligning both ch’i (breath) and hsin (the emotional heart-mind), we can avoid dwelling in these unbalanced states that undermine our health.

Master Ni offers a refinement.

Ni: “How to stop breathing?”

Me: “Meditation?”

Ni: “Helps, but no.

Breathing tied to desires.

Neutralize desires and breathing naturally stops.

Easy to say. Hard to do. But worth the effort.

Without desire. So good.” (September 26, 2002)

In this passage, breathing is directly related to our desires. Minimizing desires stabilizes breathing. Yet meditation with its breath regulation is not enough. Master Ni seems to imply that some kind of direct mental effort is required to neutralize hsin’s desires.

Could it be that exercising the te/yi synergy is required to attain this end: both deferring the gratification of our desires via te, self-restraint, and guiding our attention to the breath via yi, mind intent?