Nei-yeh (Chinese Self-Cultivation Manual)

Verse 22. Vitality: Poetry & Music temper Emotions

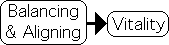

1 As for the vitality (shêng) of all human beings:

2 It inevitably occurs because of aligned and balanced [breathing].

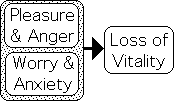

3 The reason for its loss

4 Is inevitably pleasure and anger, worry and anxiety.

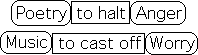

5 Therefore, to bring your anger to halt, there is nothing better than poetry.

6 To cast off worry there is nothing better than music.

7 To limit music there is nothing better than rites.

8 To hold onto rites there is nothing better than reverence.

9 To hold onto reverence there is nothing better than tranquility.

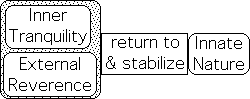

10 When you are inwardly tranquil and outwardly reverent,

11 You are able to return to your innate nature

12 And this nature will become greatly stable.

Commentary

The focus of Verse 22 is human vitality (shêng). While reiterating familiar themes, it also introduces some Confucian topics – music, poetry, rites and innate nature.

Lines 1-2:

1 As for the vitality (shêng) of all human beings:

2 It inevitably occurs because of aligned and balanced [breathing].

Regarding vitality: balancing and aligning (cheng) are the twin processes that bring about vitality. Roth suggests that breath regulation is the target of these processes. However the remainder of the verse seems to imply that emotional regulation is the target. As in Verse 21, this balancing process could refer to both ch’i (breath) and hsin (the heart-mind).

Lines 3-4:

3 The reason for its loss

4 Is inevitably pleasure and anger, worry and anxiety.

Emotions, positive and negative, lead to loss of vitality. These emotions include pleasure and anger; worry and anxiety.

Lines 5-6:

5 Therefore, to bring your anger to halt, there is nothing better than poetry.

6 To cast off worry there is nothing better than music.

Poetry is the antidote for anger. Music is the antidote for worry. Redirecting the participant’s attention towards these art forms and away from angry thoughts and future worries can presumably mitigate and distract these excessive emotions. It is well known that music, in particular, can have a calming, almost palliative, effect upon our state of mind.

Music and poetry are highly significant features of traditional Chinese culture. The classic forms of music represented a template for living. Scholars would search out ancient songs and poetry from the agricultural peasantry. They believed that this agrarian poetry reflected the innate, hence pure, nature of the preceding pastoral cultures. These passages tap into this connection.

Lines 7-9:

7 To limit music there is nothing better than rites.

8 To hold onto rites there is nothing better than reverence.

9 To hold onto reverence there is nothing better than tranquility.

The implied need to ‘limit music’ suggests that this art form, while soothing, can still be excessive. To better evoke the meaning of this passage, let us translate Line 7 in a slightly different way: “To regulate music there is nothing better than appropriate form (li).” Reversing the order of the lines for brevity: Tranquility (ching) enables us to hold onto (maintain focus upon) reverence, which in turn enables us to hold onto (pay attention to) the ‘appropriate forms (li)’/rites.

![]()

As a classical organist, this passage makes perfect sense. Remaining calm enables me to show respect for the forms, i.e. key signatures, rhythms, and such, that turn the notes into music. If I am too rigid, the composition sounds mechanical. If I am too emotional the piece can sound sloppy. Mental tranquility is the root of evoking music from a score. Music is soothing, or even cathartic, for my soul and hopefully also for the listener.

Roth translates the ideogram for li as ‘rites’, which we refine as ‘appropriate forms’. The ideogram has the symbol for ‘altar’ on the left and the symbol of ‘bronze cauldron’ on the right. The bronze cauldron represented dynastic power as far back as the Shang. Possessing the 8 sacred cauldrons indicated that a family had the support of the gods, i.e. Mandate of Heaven. This tradition preceded both Taoism and Confucianism by centuries.

Respect for li (rites) is a quintessential Confucian virtue. Performing traditional rituals presumably binds society together. The Nei-yeh’s inclusion of and emphasis upon this Confucian virtue is further evidence for the notion that the Nei-yeh is not an exclusively Taoist manual, but instead belongs to the inclusive Chinese self-cultivation tradition. This ancient tradition includes both Taoists and Confucians under its Chinese umbrella.

Lines 10-12:

10 When you are inwardly tranquil and outwardly reverent,

11 You are able to return to your innate nature

12 And this nature will become greatly stable.

Inner tranquility (nei ching) plus external reverence results in a return to and stabilization of our innate nature.

The verse’s initial lines state that excessive emotional arousal undermines vitality. The middle lines suggest that ‘inner tranquility’ and ‘external reverence’ are the roots of the music that will best soothe our vitality-disrupting emotions. The concluding lines state that these same virtues allow us to both return to and stabilize our innate nature. Calming our emotions and respect for appropriate forms, li, results in naturally returning to and stabilizing our innate nature.

Returning to our innate nature is but the first step. Stabilizing our innate nature in our core is the second step. In similar fashion, the Nei-yeh emphasizes both returning to and stabilizing jing, ch’i, shên and the Tao in our core. The stabilizing process is presumably associated with reverence, i.e. respect for the Tao, i.e. regularly practicing the Way (from earlier verses).

What is this innate nature? It can be interpreted in a variety of different ways. For millennia, Taoists have regularly spoken and written about returning to the uncorrupted state of the unborn child – the state prior to the corrupting influences of cultural conditioning. This interpretation is certainly in line with this verse. Maximizing vitality is certainly related to minimizing the cravings and excessive emotional states associated with learned behavior – both expectations and desires. Returning to and stabilizing this inborn purity could definitely enhance our vitality and be the meaning of the verse’s concluding lines.

However the ideogram that Roth translates as ‘innate nature’ suggests another interpretation. Consisting of the radical for heart-mind (hsin) on the left and the ideogram for vitality in the center, the ideogram has an individual, rather than general connotation. Every human has innate urges to fulfill unique potentials. Cultural conditioning corrupts these urges. Regularly (reverently) cultivating tranquility brings these innate urges to the foreground and simultaneously moves culturally induced urges, including the craving for money, fame and power, to the background.

Pursuing culturally induced desires erodes our vitality due to excess. Conversely, tapping into our innate nature, i.e. urges, enhances our vitality due to balance.