Great Learning & Nei-yeh: Complementary Texts

- Target Audience & Overall Intent

- Self-cultivation: Hsin (heart-mind) vs. Shen (body-mind)

- Common Word-Concepts treated in Complementary Fashion

- Nei-yeh + Great Learning = Chinese wisdom

Could each text inform the other?

Could the Great Learning, a quintessential Confucian document, illuminate the Nei-yeh, a fundamental Taoist text, and vice versa? Despite coming from supposedly opposing traditions, is it possible that the documents are complementary rather than contradictory? Could these two texts, one Confucian the other Taoist in orientation, form a greater Chinese whole? Might each brief document ‘extend the knowledge’ contained in the other? Is it possible that in conjunction, these relatively brief and simple documents construct a powerful behavioral technology that has both influenced Chinese culture for millennia and is also relevant to those of us who are immersed in our contemporary science-driven world?

To answer these questions, let us compare and contrast the Great Learning and the Nei-yeh with regard to five arenas: 1) target audience, 2) overall intent, 3) attitudes towards self-cultivation, 4) treatment of common word-concepts, and 5) their relationship to Chinese wisdom literature.

Target Audience & Overall Intent

What is the target audience of the two texts? Is it really that different?

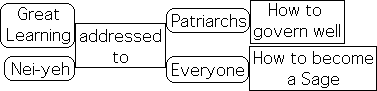

On the surface, the two texts are addressed to groups that have vast differences. The Great Learning seems to be addressed to members of the governing class, who were typically scholarly Confucians. In contrast, a noted specialist in Chinese religions suggests that the Nei-yeh is addressed to Taoist mystics. Are these audiences so far apart that they share no common interests? Or could the two groups have overlapping aims that are addressed by the two texts?

The Great Learning has distinctly patriarchal overtones. The document answers the question of how best to rule a kingdom. By extension, it is addressed to the ruling class, or at least those who govern, i.e. those who are in charge. In China, men were in charge. It is the patriarch who is to practice self-cultivation, to set things right, thereby harmonizing his family and the world. China’s scholarly class assumed this unstated, implicit Confucian message.

In contrast to the Great Learning, the Nei-yeh is more egalitarian. It attempts to answer the question: How does one go about becoming a Sage? A Sage is someone who exerts a positive effect upon the community. In this sense, the Nei-yeh is addressed to anyone who wants to become a Sage. Instead of only patriarchs, this could be women as well as men, the weak as well as the powerful.

While the Great Learning delineates what it takes to become a great leader, the Nei-yeh provides instructions on how to become a Sage. These are not mutually exclusive goals. Recall that a Sage can be a shaman, a philosopher/teacher like Confucius, the ultimate Sage, or even a Sage-King. The Great Learning’s patriarch might want to become a Sage-King. From this perspective, the Nei-yeh is not just for mystics, but instead is for anyone who wants to exert a positive effect on society. This sector of the population would certainly include the audience of the Great Learning.

In the similar fashion, the Great Learning could be for any proactive individual. While seemingly addressed exclusively to rulers, everyone, male and female, rich and poor, can benefit from its insights. This short document instructs us how to best manifest personal power in order to govern our lives, both individually and socially. This topic is of general interest to any responsible citizen. Rather than just mystics or rulers, the two documents could easily appeal to a more general and common audience, i.e. those who want to exert a positive impact upon society.

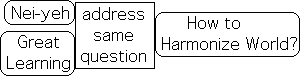

Just as the 2 documents have a similar audience, they also attempt to answer the same question: How do we best harmonize our community?

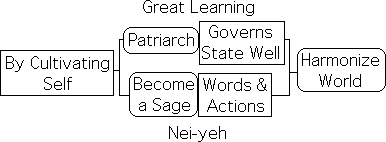

The 2 documents even come up with the same answer – self-cultivation. According to the Great Learning, ‘cultivating the self’ is a prerequisite for governing well, i.e. bringing peace to the land – harmonizing the world. According to the Nei-yeh, through self-cultivation, we become a Sage. Then our words and actions will naturally bring harmony to our community.

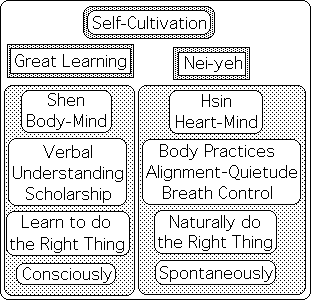

Self-cultivation: Hsin (heart-mind) vs. Shen (body-mind)

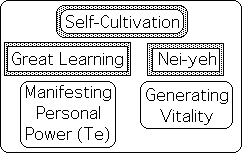

Both the Nei-yeh and the Great Learning are, at least in part, addressed to any human that hopes to exert a positive influence upon the planet. Further they attempt to answer the same question – how to best harmonize our world. Both texts arrive at the same answer – self-cultivation. The Great Learning states explicitly that self-cultivation is the key to the effective governance of self, family and state, while the Nei-yeh delineates the essential components of self-cultivation.

Although the common focus is self-cultivation, what does each document mean by both self and cultivation? What is the aim of self-cultivation? Are these perspectives complementary or oppositional?

On the most fundamental level, the two documents have a different conception of which self they are cultivating. The Great Learning stresses the importance of cultivating shen, the body-mind. The body-self (shen) could be likened to our social/public/cultural self. We cultivate shen in order to exert an influence on the socio-political world. In contrast, the self-cultivation implied by the Nei-yeh aims at cultivating the heart-mind (hsin). Hsin could be likened to our personal/psychological self. We cultivate hsin in order to attract the cosmic energies.

Besides cultivating different selves, the orientation of each text is also different. For the Nei-yeh, self-cultivation tends to be physically oriented – breath control and body alignment. In contrast, the Great Learning emphasizes understanding. ‘Investigating things’ enables one to ‘extend knowledge’, which is a basis of self-cultivation.

Besides differing on their self-cultivation techniques – mental understanding vs. physical practices, the result is also different. For the Nei-yeh, we naturally do the right thing after years of body practices. Later Taoist texts even stress the importance of behaving spontaneously. For the Great Learning, we learn to do the right thing after years of scholarship. Instead of spontaneously, we speak and act deliberately.

The end result of both documents remains the same. Cultivating the self results in speech and action that harmonizes the human world.

The two documents also have a slightly different take on the results of self-cultivation. According to the Great Learning, self-cultivation enables us to manifest our personal power (te) more effectively. According to the Nei-yeh, personal vitality is the result of self-cultivation practices. Rather than contradictory aims, personal vitality is certainly linked with our capacity for manifesting personal power.

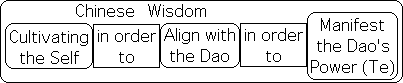

Self-Cultivation => Tao Alignment => Te Personal Power

Vitality and manifesting personal power are associated with the Tao. Although not explicitly stated, a common theme emerges. Both Confucians and those Chinese that were eventually labeled Taoists started with this assumption: Practicing self-cultivation ultimately results in alignment with the Tao, both social and personal. Aligning with this Cosmic Wave enables us to best manifest personal power, te. Chinese philosophers frequently refer to this as the Power of the Way, the Tao’s Te.

Common Word-Concepts treated in Complementary Fashion

Complementary perspective on self-cultivation

The overall themes of both texts are exceedingly similar: self-cultivation, manifesting personal power, and self-cultivation. Although the Great Learning has a Confucian orientation, it employs many of the same ideograms as word-concepts and shares many of the same concerns as the Nei-yeh. Do the two texts echo each other, or do they provide complementary perspectives?

Many of same word-concepts: Redundant or Complementary?

What are some of the common word-concepts? Are they employed in a complementary or oppositional fashion? Are the insights contained in the two documents merely redundant or does each text really illuminate and refine the insights found in the other? To answer these questions, let us examine how the two texts treat some common word-concepts.

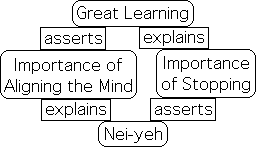

NY asserts that stopping important; GL provides the reasons why.

The Nei-yeh implies that the ability to stop is a positive virtue with regard to both our desires and emotions. But it doesn’t state why. The Great Learning delineates the logic behind this process. The text clearly states that the ability to stop in the right time and place is important because this leads to balance, tranquility and harmony, which are at the root of our critical thinking skills and achieving our aims. In such a way, the Great Learning illuminates the Nei-yeh.

How about vice-versa?

GL asserts that ‘aligning hsin’ important; NY provides the reasons why

Both documents stress the importance of mental alignment. In fact, the Great Learning and the Nei-yeh employ identical ideograms for ‘correct the mind’ and ‘aligning the heart-mind’. While the Great Learning merely asserts that it is important to align hsin, the Nei-yeh goes into great detail to describe how to achieve this state and why it is so important. In this regard, the Nei-yeh stresses aligning the body, regulating the breath, and pacifying the mind.

GL manifesting Te, NY developing Te

The Great Learning provides instructions in how to best manifest our personal power, te, in order to govern our personal and public lives. Yet, it doesn’t reveal how to generate it. In complementary fashion, the Nei-yeh instructs us how to develop te, our inner power. ‘Developing te’ plays a part in attracting the cosmic energies. With these energies in our core, we are able to better manifest te – the focus of the Great Learning. Rather than taking opposing positions, the 2 documents have interlocking themes – how to develop and then manifest te.

NY positive results of yi, GL purifying yi

Both documents also indicate the importance of yi (will/awareness/mind intent). While the Nei-yeh articulates the positive results of exerting yi, the Great Learning stresses the importance of ‘making yi (the will) sincere’. Put another way, it important to first purify the will. However the document doesn’t tell us what this means. Cengzi’s Commentaries on the Great Learning clarifies the meaning of this fundamental process as well as some of the key concepts in the Nei-yeh. Ensuing chapters will examine this significant commentary in more detail.

Nei-yeh + Great Learning = Chinese wisdom literature

Larger category of Chinese wisdom?

We’ve seen many ways in which the Nei-yeh and the Great Learning complement each other in many ways. As exhibited, both texts stress the importance of self-cultivation. The Nei-yeh has a physical approach, while the Great Learning has a verbal approach. Rather than mutually exclusive, the two orientations illuminate unique facets of the same gem. This is but one instance of this confluence of aims.

Same school?

Do the two texts, one Taoist, the other quintessential Confucian really belong to opposing philosophical traditions? Is there another way of viewing the relationship between these two documents that are supposedly from competing schools? While scholars tend to differentiate Taoism and Confucianism, could each philosophy ultimately fall under the larger umbrella of Chinese wisdom literature?

No Taoists during Warring States Era

To better propose some answers to these questions, let us examine the time at which the two texts were composed – the Warring States Era. There were no self-identified Taoists during this time or for many more centuries to come. Put another way, Taoism didn’t even exist when our two texts were written. Historians assigned this label to a school of thought that wasn’t even aware of its difference from Confucianism.

To reflect this reality, Roth, the noted Taoist scholar, refers to the Nei-yeh as ‘Taoistic’. This is because it contains many standard features that eventually became incorporated into classic Taoism. However, key Taoist elements are lacking in this brief instruction manual, while it contains Confucian elements. Neither belonging completely to one school nor the other, the text shares a little of both.

During this time period in the centuries before the Common Era, future schools of thought were only tendencies. Many traditional philosophies were just in their nascent stage: yin-yang theory, the five-phase theory, and Taoism, both alchemical and liturgical. Although there were as yet no institutions, the multiplicity of philosophies had one feature that bound them as a group. They consisted of literature that required a literate class.

Documents Written for the Ju, China’s Literate Class,

not common workers

Although possibly deriving from an oral tradition, our documents consist of a series of Chinese ideograms that are unintelligible to any but a select group. Until the middle of the 20th century, only 1%, at the very most, of the population could read. This small sliver of the population were privileged members of society. This privileged class did not include farmers, laborers, or common soldiers. The Chinese underclass had neither the time nor the energy to learn how to read, much less pursue self-cultivation practices.

Only the jun-zi class literate

China’s privileged class was generally comprised of the literate jun-zi. This literate class emerged from the shih, the Shang military aristocracy (≈ 2nd millennium BCE). Originally belonging to the landed aristocracy and warrior class, many became administrators as fortunes rose and fell. Both the Nei-yeh and the Great Learning were written for the jun-zi, as they were the only ones that could read.

Ju could be scholars, generals, mystics or shamans

The literate jun-zi were not only male scholars, as some assume. They could also be generals as well as doctors/healers, mystics, and even shamans. Although outside the norm, women belonging to the privileged ju class could also become warriors, rulers, (one even became an Empress), and mystics (one of the Taoist Immortals is a woman).

Both-and rather than either-or categories

These societal roles were not necessarily exclusive either-or categories. For instance, a general could be both a scholar and a mystic. This was true in China then and for another few thousand years. Wang Yang-ming, the notable Confucian that we referenced regarding the Great Learning, falls into the blended category of scholar-general. Further mystics could be warriors. The Buddhist disciples in the famous Ming novel, Journey to the West, are formidable warriors that practice self-cultivation austerities. In Three Kingdoms, another famous Chinese novel, a fallen king engages a reclusive Taoist monk or shaman to lead his army. These are entirely believable scenarios for the Chinese.

No clear cut distinctions between readership of 2 texts

The point is that there were no clearly defined boundaries between warriors, rulers, healers, mystics and shamans in the literate jun-zi class. Similarly there were no clear-cut distinctions between those jun-zi who might read our two texts. One instructs as to how to govern and the other how to become a Sage. These are not mutually exclusive goals.

Indeed, the Chinese consider the classic Sage-Kings of the early Chou Dynasty to be both wise men and rulers, as their title suggests. Even Chinese architecture reflects the dual role of leadership. The Emperor sits between the Culture Hall and the Martial Hall. His role is to balance both perspectives – one based in literature, the other in military.

Chia-hsia Academy: example of intellectual interaction

Literate Chinese, whether mystic, ruler, warrior or shaman, could have read and discussed our two documents. Rather than a dogmatic debate, there was a dynamic dialogue between the members of these diverse groups. As an example of this vital cultural exchange, a variety of philosophers from many traditions and perspectives were assembled at the Chia-hsia Academy to exchange ideas and learn from each other. Rather than competing over who was right and who was wrong, the philosophers engaged in a dialogue over many common issues. In general, they were attempting to refine their understanding regarding a socially responsible individual’s relationship with self and society as a whole.

Like schools in academia

Rather than opposing religions, the variety of schools could be likened to fields in academia. Research in one field corroborates and refines insights from another. Chemists don’t attempt to convert Physicists or prove that they are wrong. Instead they share insights to further their own investigations.

Not which is true; rather what can we learn

Physiology and psychology reveal different, not contradictory, aspects of health. We employ the insights from each discipline to improve our existence. Instead of asking the question, “Which field is true?”, we ask, “What can I learn that will make my life better?” In fact, many of us examine the insights from many disciplines with the aim of self-improvement – both individually and socially. In similar fashion, I am examining ancient Chinese wisdom literature, not to determine if it is right or wrong, but to discover how it can inform my 21st century life.

Chinese wisdom resonates with Personal Experience

Although coming from unique perspectives, the Taoist Nei-yeh and the Confucian Great Learning ultimately shed light on the same topics. This Chinese wisdom resonates with my personal experience. This document is designed to share my insights.

Extracting Chinese wisdom for personal use

In similar fashion to our two texts, this more lengthy work is also addressed to those of us who question our personal role and social obligation. We ask ourselves: How do we maximize the possibility of both fulfilling personal potentials and exerting a positive influence upon the community? To answer this question, we hope to extract the complementary Chinese wisdom contained in the documents with the intent of applying the insights to our behavior. In pursuit of this end, let us now proceed into some specific textual analysis and comparison.