Great Learning & Nei-yeh: Importance of Stopping in Perfection

- Stopping in Tranquility attracts the Tao’s Vitality

- Stopping Accumulating Knowledge & Endless Mental Loops for Vitality

- Stopping Cravings & Obsessions

- Stopping Destructive Behavioral Momentum

- Stopping in the Perfection of the Moment to develop Presence

In the prior chapter, we illustrated how the Nei-yeh and the Great Learning share a common audience, common concerns, and even common word-concepts. More importantly, they share a common theme – the importance of self-cultivation. While having many commonalties, the two texts, one Taoist and the other classic Confucian, don’t merely reiterate the same insights. Instead each illuminates the insights of the other. Despite coming from what are traditionally thought to be opposing traditions, they can be viewed as complementary documents. This chapter focuses upon a specific example of this feedback loop of understanding.

Stopping: an essential self-cultivation process

Both the Nei-yeh and the Great Learning stress the importance of the ability to stop. An implicit assumption behind both texts seems to be that stopping is an essential process in the Way, the Tao, of self-cultivation. Rather than repeating common themes, the two texts reveal complementary aspects of this self-cultivation process.

The Nei-yeh contains multiple references to the importance of stopping – (Verses 8, 19 and 23). It provides some excellent examples, but no underlying structure. In contrast, the Great Learning provides a theoretical background, but no examples. Rather than representing opposing schools, once again the two texts illuminate different facets of the same Chinese wisdom.

What can these two classic Chinese texts, one Confucian and the other presumably Taoist, teach us about stopping? According to these documents, the ability to stop is associated with many positive processes: 1) enhancing cognitive abilities 2) achieving our aims, 3) attracting vitality, 4) avoiding over-thinking, 5) resisting overeating, 6) correcting behavioral momentum, and 7) developing presence. Let us see why.

Stopping in Tranquility attracts the Tao’s Vitality

Stopping is a major theme in the Great Learning. It begins by asserting that ‘stopping in perfection’ is one of the three essential processes of the Way – the Tao of the learning of greatness. As such, it is of utmost importance.

GL Section 2: Stopping > Stability > Tranquility > Enhanced Cognitive Skills > Achieving Goals

The document’s 2nd section consists of a 5-step logical if/then sequence that clearly delineates why the ability to stop is so important. Paraphrasing: Knowing when to stop leads to stability. Maintaining stability results in tranquility, which in turn leads to peace [of mind]. A peaceful mind enhances our cognitive abilities. With enhanced critical thinking skills, we are more likely to achieve our aims. In brief, the Great Learning asserts that the ability to stop at the right time and place results in stability, tranquility, peace, optimal mental capabilities and accomplishing our goals.

Stopping -> Stability -> Tranquility -> Enhanced Cognitive Skills -> Achieving Goals

Tightrope Walker Metaphor

While the terse text doesn’t provide a rationale for its assertion, the following metaphor provides a plausible linkage between the concepts. The sequence evokes the image of a tightrope walker. If he can stop at the balance point rather than going too far, he is stable and at peace and can better reach the other side. Conversely, if he moves past the center, his balance is thrown off. The imbalance consumes his cognitive abilities. Instead of reaching the other side, he expends his available energy attempting to regain his equilibrium.

Balance vs. Balancing

The tightrope walker metaphor epitomizes the difference between a permanent state and the state of becoming. Our high wire artist never attains balance. Instead he is in a constant state of balancing. Similarly, humans must regularly balance their appetites, whether for food or knowledge, in order to survive. However, after fulfilling our appetites, such as hunger and thirst, we must stop before going too far. Excess in any direction is harmful to the organism as it leads to imbalance.

Nei-yeh: Stopping > Tranquility > Dao > Vitality

The Nei-yeh adds vitality to the list of positive advantages of stopping in perfection. The Great Learning asserts that knowing when to stop results in tranquility. The Nei-yeh repeatedly stresses the importance of the same tranquility (ching). A tranquil mind both attracts and stabilizes the cosmic energy sources – jing, ch’i, shên, and the Tao. Knowing when to stop leads to balance, which in turn leads to tranquility. Inner calm is a prerequisite for the physical and mental vitality associated with the Tao. Vitality is yet another reason why ‘stopping in perfection’ is so important.

![]()

Stopping Accumulating Knowledge & Endless Mental Loops for Vitality

While revealing the positive results of stopping, the Great Learning doesn’t provide any examples and leaves many questions unanswered. What does ‘stopping’ consist of? When and to what does it apply? What is ‘perfection’?

‘Stopping in perfection’ can certainly be applied to thinking and the accumulation of knowledge. To see how, let us examine some specific verses from the Nei-yeh. From Verse 8 lines 10-13, “When there is thought, there is knowledge.When there is knowledge, then you must stop. Whenever the forms of the mind have excessive knowledge, you lose your vitality.”

Too much information, i.e. TMI, appears to be the focus of this segment. The text is fairly straightforward. Because excessive knowledge results in loss of vitality, we must stop accumulating information. This suggestion is especially appropriate in our Age of Information. Rather than constantly filling our mind with ‘interesting’ intellectual garbage, e.g. news regarding sports, politics and celebrities, the Nei-yeh cautions us to ‘stop’ before excess knowledge erodes our vitality. Modern psychological research affirms this insight. Information overload is bad for our health.

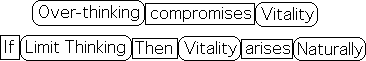

Lines 11-13 from Verse 20 express a similar sentiment. Paraphrasing: “Don’t over-think things. Limit thinking to the appropriate degree and vitality will come naturally.”

This particular passage seems to be warning us against the possibility of ‘over-thinking’ things. Analysis of events and sensory input is essential to maintaining our well-being. However, it is important to know when to stop this intellectual process and just be. Over-thinking compromises our vitality.

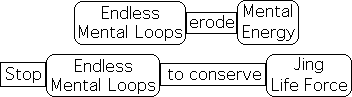

For example, our thought processes frequently enter endless loops, whereby we engage in the same mental patterns over and over again. The mental process ends where it began – having gone nowhere. These cognitive circles can be personal or in interpersonal interactions.

By spinning our cognitive wheels, we waste mental energy. After becoming aware that we are engaging in these repetitive cognitive processes that are going nowhere, it is imperative that we ‘stop on a dime’, i.e. immediately, so as to not waste any more energy. By pulling out of these endless mental loops as soon as possible, we are able to conserve our life force (jing).

The Nei-yeh’s Verse 19 provides another example of the importance of stopping. The verse starts with the positive. Paraphrasing: “We can concentrate our qi/ch’i (breath) so that it becomes shên (cognitive abilities).” The verse follows with some warnings that would presumably block this exalted process. Line 6: “Can you stop in peace? Can you cease in peace?” The verse seems to be suggesting that our ability to transform qi into shên will be compromised if we can’t stop in mental tranquility.

![]()

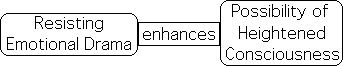

While peace seems to be a desirable state, many humans can’t ‘cease’ there and pursue emotional drama instead. Rather than ‘stopping in peace’, we inadvertently create stressful situations. As drama inevitably enters our lives, we don’t need to generate it. This craving for drama compromises our ability to abide in the state of peace.

![]()

Mental tranquility seems to be one of the prerequisites for refining qi into shên. To provide a modern context, we can liken this refinement process to spiritual transformation for the mystic or perhaps inspiration for the artist. With the proper preparation, raw qi energy can be transformed into the more refined shên energy that can be equated with the heightened state of consciousness or even the capacity for awareness that is associated with transformation or inspiration. In such a way, resisting this craving for emotional drama enhances the possibility of higher states of consciousness.

The ‘stopping’ muscle also applies to emotions. Verse 22 of the Nei-yeh speaks of the importance of ‘bringing anger to a halt’. Regulating our verbal thoughts rather ‘going with the flow’ is essential if we are to achieve the Tao, the Flow that results in vitality. Allowing our mental habits to fuel the fire of anger by accumulating example after example amplifies this destructive emotion. If we instead ‘stop’ in pure feeling rather than shifting into the verbal realm, the pulse of anger will fade more rapidly.

As an example of parallel focus of the two texts, the ideogram that the Nei-yeh employs for ‘peace’ is the same as ‘peace throughout the land’ in the Great Learning. Can we stop in the perfection of peace, rather than moving onto greed, the root of war?

Stopping Cravings & Obsessions

This ‘stopping’ virtue has many other applications besides thought. It also applies to behavior. In a discussion of the Tao of eating, Verse 23 from the Nei-yeh states that it is important to stop when full. Why? Because ‘overfilling with food impairs qi flow, and causes our body to deteriorate’. Continuing to eat after full – after ‘attaining perfection’ – has significant negative consequences, both physical and energetic. We lose our psychic balance, which has a negative impact upon cognitive skills, at least according to the Great Learning.

The eating metaphor can be employed as a template for desires – a typical Chinese extension. If we can stop after fulfilling our desires, we remain in balance, physically and mentally. However, if we continue on after attaining perfection, our lives become unbalanced and we will be less likely to achieve our goals. For instance, if we continue drinking after attaining the ‘sweet spot’, our mental state is significantly impaired, which frequently leads to bad decisions.

![]()

Verse 23 further states that if our mind is obsessed with food, we won’t be able to stop eating once we start. Extending the eating metaphor to desires: if we are obsessed with fulfilling our desires, whether physical, emotional or spiritual, we won’t be able to stop the process once it begins.

![]()

The inability to stop in perfection due to obsessive desires leads to an unbalanced emotional life, which disturbs our tranquility. Lacking peace of mind our cognitive skills are compromised and thereby our ability to accomplish our goals.

![]()

Because money is connected with the fulfillment of our material desires, the accumulation of capital frequently becomes an abstracted craving. Humans who are infected with this craving for money are unable to ‘stop in perfection’ even though the very health of the planet’s ecosystem is at stake.

Stopping Destructive Behavioral Momentum

The ‘stopping’ process has multiple features that are associated with mental health. The ability to stop indicates that we are somewhat in control of our behavioral momentum. This stopping ability is associated with self-control, restraint, and deferred gratification.

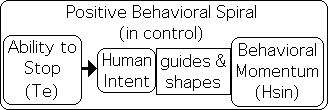

The Chinese word-concept ‘te’ (inner power) is linked with the ability to stop. Te is frequently employed in combination with yi, i.e. will or mind intent. By employing the te/yi synergy, i.e. self-restraint and positive intention, we are able to guide and shape our behavioral momentum. In such a way, we are able to gain greater control of lives by simultaneously stopping and guiding our actions and thoughts.

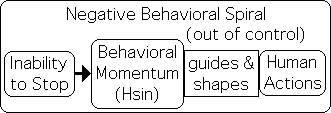

Hsin, our heart-mind, can be viewed as the repository of inclinations and tendencies associated with our behavioral momentum. This momentum includes both probabilities and trajectories. If we allow hsin, our behavioral momentum, to propel us forward without guidance, we react to circumstances. Blindly following our cravings frequently results in negative consequences.

The appendage ‘oholic’ exists to describe those who are unable to control their desires, which have turned into cravings. Alcoholic, food-oholic, spend-oholic indicate individuals who drink, eat, or spend too much – too much in the sense that it has a negative impact upon their lives – health, job, relationships, survival.

When we don’t have the ability to stop, hsin, our innate behavioral momentum, guides and shapes our speech and action. Without the te/yi synergy guiding our path, desires, senses and negative thought patterns can easily seize control of our lives. Participating in excessive actions reinforces negative behavior patterns, which further erodes our ability to stop. This process can create a negative feedback loop, which can easily spiral out of control. As this destructive behavioral momentum grows, our ability to stop shrinks. As this negative behavioral spiral grows, it grows increasingly difficult to control, just like an undisciplined child.

We don’t have to be victims of our accumulated behavioral momentum. We can instead employ our te/yi synergy to restrain and guide hsin. This shaping process generates a positive feedback spiral. Each repetition of ‘positive’ behavior increases the probability that we will engage it again. In such a way, we both strengthen the te/yi synergy and increase the chances that hsin will ‘naturally’ move in a positive direction.

Stopping in the Perfection of the Moment to develop Presence

Knowing when to stop is partially related to awareness of the moment – presence. If we are able to ‘pay attention’ to each moment, we are aware when we reach the state of perfection, whether the right amount of food, the right amount of intoxication, or the right amount of gambling. If we are at least aware of this moment of balance, we can at least attempt to stop there, rather than proceeding blindly into excess. Excessive behavior has the potential to both imbalance our lives and impair our cognitive skills.

Just like the te-yi synergy, this awareness of the moment, this presence, must be developed. In this case, ‘stopping in perfection’ refers to pausing in and savoring the moment rather than rushing off to the next experience, the next thought, the next text message, or the next alert. While Yoga and Tai Chi are physical practices that are designed to increase bodily awareness, meditation can strengthen awareness of the moment – sheer presence.

The Chinese have a concept wuji that addresses this difference. While taiji means to consciously extend to the limit, wuji means ‘without limit’. Stopping at the end of the Tai Chi forms enables us to exercise our ability to tap into the limitless presence of wuji.

While these exercises help, we can practice stopping in the perfection of the moment at any time. However, sometimes stopping is too abrupt. Like binge dieting, it can evoke an equal and opposite reaction. Slowing down our behavior, thoughts and movement can be a more effective means of achieving the balance point.

As before, the more regularly that we stop in the perfection of the moment, the easier it becomes. The probability of stopping behavior grows with each repetition of the process. This process sets up a positive feedback loop that leads to balance, tranquility, strong cognitive abilities and the ability to fulfill our goals. If we regularly practice stopping in the perfection of the moment by whatever, we simultaneously develop our presence, our potential for awareness.

![]()

It is evident from this discussion that both the Nei-yeh and the Great Learning consider the ability to stop in perfection to be of utmost importance. Rather than repeating common themes, each text contributes unique insights to the dialogue. In such a way, the Confucian classic and the Taoist self-cultivation manual are complementary texts.