5. Nei-yeh 10 >13: Influencing the World Naturally

- Verse 10. Well-ordered Mind leads to Well-ordered World

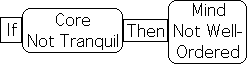

- Verse 11. If Not Tranquil, Then Mind Not Well-ordered. Aligning Body assists Inner Power (te).

- Te: Ancient History & Contemporary Science

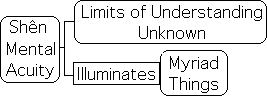

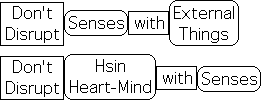

- Verse 12. Shên is the source of intuitive understanding. Over-stimulated Senses disrupt Mind, which drives away Shên.

- Shên: Modern Definition & Ideogram

- Zhöng: middle, center or core

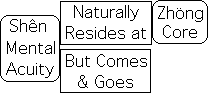

- Verse 13. Shên required for Well-ordered Mind. Centered Jing brings Shên. Clean out Shé to stabilize Jing. This Practice limits Desires, which leads to Aligned Mind.

- Hsin: our innate nature, not a cosmic energy source

- Natural, i.e. effortless, for the Conservation of Mental Energy

- Summary: Verses 10>13

Generally speaking, the first 9 verses of the Nei-yeh introduce some prime concepts and their relationships. The primary focus is upon our internal state. The next few verses illustrate how we are able to exert a positive influence upon our planet. These verses indicate that the Nei-yeh’s main aim is not enlightenment or release from this realm of suffering. Instead the goal is to become a Sage, i.e. someone who exerts a positive effect upon the world.

Verse 10. Well-ordered Mind leads to Well-ordered World

- With a well-ordered mind (hsin) within you,

- Well-ordered words issue forth from your mouth,

- And well-ordered tasks are imposed upon others.

- Then all under Heaven will be well-ordered.

- "When one word is grasped,

- All under Heaven will submit.

- When one word is fixed,

- All under Heaven will listen."

- It is this [word "Way'] to which the saying refers.1

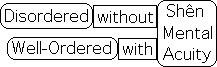

Verse 10 provides reasons as to why a well-ordered hsin (heart-mind) naturally exerts a positive influence upon the world. When hsin is well-ordered (aligned), then our words and the tasks that we assign others are also well-ordered. When our speech and behavior are well-ordered, the human world, i.e. ‘all under Heaven’, also becomes well-ordered.

![]()

The verse ends by stating that 'all under Heaven' will both ‘submit’ and ‘listen’ if but one word is both ‘grasped’ and ‘fixed’. Roth suggests that the word is ‘Tao’.

![]()

We must both understand and stabilize the Tao. But what does the word Tao refer to? Is it a state of mind, a process, or perhaps a behavioral technology? We suggest that the Tao refers to the Way, i.e. the logical sequence, that is identified in the first four lines of the verse. A well-ordered mind is the basis of the words and actions that lead inevitably to a well-ordered world.

This significant process permeates Chinese thought. A similar notion is also contained The Great Learning, an incredibly influential Confucian document. The short text ends with the lines:

“From the king down to the common people, all must regard the cultivation of the self as the most essential thing. It is impossible to have a situation wherein the essentials are in disorder, and the externals are well-managed. You simply cannot take the essential things as superficial and the superficial things as essential.”2

Stated another way: self-cultivation precedes correct and effective socio-political action. Conversely, inner turbulence leads to external turbulence. This is a feature of the Tao, the Way, of the Great Learning.

It is evident that self-cultivation is the essential root in The Great Learning. According to this same document:

“Wanting to cultivate themselves, they first corrected their minds.”

It seems that a ‘well-ordered mind’ could be one of the aims of self-cultivation. With a well-ordered mind (hsin), we will exert a positive influence upon the world around us. How do we align hsin? First, what causes our mind to be out of alignment?

Verse 11. Not Tranquil = Not Well-ordered Mind. Align Body to assist Inner Power (te).

- When your body is not aligned,

- The inner power (te) will not come.

- When you are not tranquil within (zhöng),

- Your mind will not be well-ordered.

- Align your body, assist the inner power (te),

- Then it will gradually come on its own.

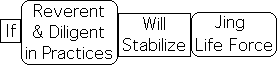

Verse 11 states simply that if our core (zhöng) is not tranquil, then hsin, our heart-mind, will not be well-ordered. Tranquility (ching) is a precondition for a well-ordered mind.

Further te, our inner will power, is blocked if our body is not aligned.

![]()

The process of body alignment assists te to naturally comes on its own.

![]()

Recall from Verse 2 that te attracts the elusive ch’i energy into our center. ‘Developing te’ stabilizes ch’i and produces wisdom. The current verse states that ‘body alignment (cheng)’ assists te. Body alignment comes first, as cheng assists te, which in turn secures and stabilizes ch’i, the source of our vitality.

Another interpretation could be that the process of aligning our body simultaneously develops te, our will power. To attain body alignment, we must exercise both guidance and restraint. This process strengthens our complementary mental muscles, the synergy of te and yi. The universal aspect of te could easily encompass this mental synergy.

Te: Ancient History & Contemporary Science

The word/concept ‘te’ has a long history in Chinese thought. During the Shang Dynasty 2nd millennium BCE, the military aristocracy, the shih class, believed that only they, the ruling class, possessed ‘te’ as a virtue. In fact, they were rulers because of this supposed fact; ‘te’ allowed them to rule. Because the agrarian peasantry did not have ‘te’, they were considered to be closer to beasts of burden.

Although each member of the shih class was born with te, this critical virtue was more obscured in some than others. However with proper guidance and practices, it was possible to clean the mental mirror so that an individual’s innate virtue (te) might shine through.

Even under this perspective, te was developmental. Although we have te from birth, culture and family must encourage it. It was and is the parents’ responsibility to nurture this crucial virtue.

Te eventually became one of the 5 Confucian virtues. While jen (compassion) was the prime virtue, the individual could only achieve jen through te.

What is ‘te’?

Let us attempt to make sense of the Chinese word-concept ‘te’ from a 21st century perspective. Cognitive scientists have begun exploring a human trait deemed ‘deferred gratification’. This trait is associated with a successful life in terms of career, relationships and monetarily.

Studies have also shown that this virtue shows up very early in infancy. Some think that it is genetic, i.e. innate. Others believe that it can be developed to some extent. Indeed one of the tasks of parenting is to exercise, thereby develop, this mental muscle in their offspring. Discipline is primarily administered to train children to restrain themselves from performing some kind of inappropriate behavior. This interpretation fits neatly with the ancient belief system of the Chinese ruling class. It also dovetails with our notion that te is a mental muscle associated with self-restraint. Our reading of the Nei-yeh supports this viewpoint, as we shall see.

Verse 12. Shên is the source of intuitive understanding. Over-stimulated Senses disrupt Mind, which drives away Shên.

- The numinous [mind] (shên), no one knows its limit.

- It intuitively knows the myriad things.

- Hold it within you; do not let it waver.

- To not disrupt your senses with external things,

- To not disrupt your mind (hsin) with your senses,

- This is called 'grasping it within you (zhöng)'.

Verse 12 focuses upon shên. Roth translates shên as ‘numinous’. Although risking misleading connotations, I prefer the more traditional ‘spirit’ for shên, as it is more accessible to the contemporary mind. Both ‘spirit’ and ‘numinous’ suggest something ethereal that transcends the everyday (earthly) mind, hsin. Shên is another key concept of the Nei-yeh that we will examine in more detail. Although this important word-concept has multiple meanings in the Chinese tradition, I am going to attempt to confine the meaning to the Nei-yeh’s context.

According to this verse, no one knows the limits of shên, which intuitively understands ‘the myriad things’. The first character in line 2, chao, means to illuminate or make manifest in the light. Roth's ‘intuitively’ is an interpretive rending of the term. Under this reading, shên illuminates clearly and orders what enters the senses, so that hsin is able to reflect clearly, without misapprehension, about the myriad things.

Because of these positive features, we are counseled to hold or guard shên in our center (zhöng). In similar fashion to jing, ch’i and the Tao, the implication is that shên is some kind of external cosmic energy that we want to attract to and stabilize in our core.

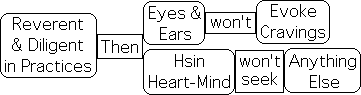

The verse continues on to describe what conditions repel shên. External things presumably disrupt our senses and our senses disrupt hsin, our heart-mind. These disruptions are to be avoided if we are to retain shên with its powerful cognitive skills.

Avoiding these disruptions is the process of grasping shên within our core (zhöng). The ideogram for grasping can also be translated as ‘getting, developing, nurturing, or preserving’.

![]()

In other words, sensuous cravings disturb the tranquility of hsin. Disrupting hsin’s tranquility repels shên's ability to 'intuitively understand the myriad things' or alternately ‘clearly illuminate and order incoming sensual input’.

From prior verses, our sense-desires disrupt the tranquility that is the foundation of the well-ordered mind (V11). Further a well-ordered mind is the basis of effective speech and action that exert a positive influence upon the planet (V10). In brief, emotional turbulence produces disruptive effects that both jumble our well-ordered mind and repel shên from our core (zhöng).

Shên: Modern Definition & Ideogram

To gain a better understanding of shên’s connotations for the Chinese let us look at some definitions and examine its ideogram.

Following is the modern definition for shên:

“ 1) god, deity ; 2) spirit, mind; 3) expression, look; 4) supernatural, magical” 3

When the ideograms for shên and jing are combined the definition becomes:

“1) spirit, mind, consciousness; 2) essence, gist, spirit; 3) vigor, vitality, drive 4) lively, spirited" 4

In other words, shên can signify both an external deity, perhaps even a ghost, and an internal spirit associated with our mind. This dual nature is reflected in Chinese mythology. Humans are born with shên. When we die, shên becomes an active spirit5.

To get a better notion regarding its personal meaning, let us examine the shên’s calligraphy. The ideogram combines the pictograms for ‘divine’ on the left with ‘to extend, increase, state, report’ on the right.

The ancient Chinese took divination seriously. Their leaders examined the cracks on tortoise shells to determine the course of action for affairs of state. Chinese calligraphy supposedly derived from these same cracks. Further the I Ching, the first Chinese classic, can be employed as a form of divination.

The pictogram on the right derived from 2 hands holding a rope for extension6. The hands could be alternately employed to climb upwards. In the case of this pictogram, extension was associated with ‘the alternate expansion of two natural powers’7.

Combined with the pictogram for divination, it grants the impression of extending into the divine world for guidance. The combination evokes the notion that directives are coming from Heaven. The implication of the ideogram is that shên’s insights derive from divine sources. If we can tap into shên energy, inspiration is the result.

Let us provide yet another nuance for this charged idea-concept. Isabel Robinet, the French Taoist scholar, defines shên as “constelling force”. This is admittedly a clumsy term, but saves it from associations with mystical or other-worldly connotations. Shên is that force/energy in the self that centers/controls/gives order to the multiplicity of the body just as the pole star organizes the stars as they ‘circle’.

Confucius: “The king is like the pole star; he faces south and (without force) the country orders itself.” Under this way of thinking, shên is the self-constelling power within a human.

Zhöng: middle, center or core

Zhöng8 is another important Chinese word/concept. Roth translates zhöng as ‘within’. I prefer ‘center’ or ‘core'. It is most commonly translated as ‘middle’.

The word

In the Chinese/English Dictionary, zhöng is translated as:

1) center, middle;

2) in, among;

3) between two extremes;

4) medium; or

5) China.

Notice that the middle is not without tension. Instead it is ‘between two extremes’. In the right context, zhöng or middle could even mean China, itself. Just as tao means ‘path’, ‘method’, and ‘Taoism’, simultaneously, zhöng means ‘middle’, ‘between two extremes’, and ‘China’ simultaneously.

Ideogram for zhöng, arrow hitting target, attaining the center

Zhöng’s ideogram is simple and yet instructive – a vertical line through the center of a box.

![]()

"It represents a square target, pierced in its center by an arrow."9 By extension some other translations of the word include, "To hit the center, to attain."10 Hence this symbol does not just represent the center, but instead has the connotation of achieving the center. Attainment of the center is a dominant feature of Taiji practice as well as Taoist thought. Remember this is not a passive state, but instead a constant redefinition, and re-attainment of the center.

To further indicate the importance of this concept in Chinese, this ideogram is also used extensively in Chinese calligraphy as a part of other words.

Zhöng is normally a noun denoting a particular place or point of balance. In this verse, zhöng is the residence of shên, which functions to govern and balance the body and all its components, including hsin, by means of its numinous power. Socially, the emperor centers the Imperial Palace, which centers the capital, which centers the guo "empire/state".

In similar fashion, the emperor functions to balance the extended empire by force of the unlimited shên, which it guards at the center. Traditionally it was understood/argued that the emperor's numinosity brought order to the empire without ever requiring him to leave his palace/center, within which he was guarded. In terms of our discussion, understanding and divine inspiration radiate from the center (zhöng) when shên is located there.

It seems that, in addition to jing, ch'i, and the Tao, we also want to attract and stabilize shên at our core. Emotional turbulence prevents this from happening by throwing us off our balance point – zhöng. How are we to achieve this emotional balance that brings inspiration and clarity?

Verse 13. Shên required for Well-ordered Mind. Centered Jing brings Shên. Clean out Shé to stabilize Jing. This Practice limits Desires, which leads to Aligned Mind.

Verse 13 continues relating the benefits of shên (spirit energy) and a well-ordered hsin (heart-mind). It also incorporates jing (our life force) into this network. This song-poem refines our understanding of the relationship between this trio of fundamental process-energies: jing, shên, and hsin. (Aside: this continuity of topics is further evidence for the Nei-yeh’s developmental nature.)

- Shên (spiritual energy) naturally resides within.

- One moment it goes; the next moment it comes.

- And no one is able to conceive of it.

- If you lose it, you are inevitably disordered.

- It you attain it, you are inevitably well-ordered.

- Diligently clean out its lodging place (shé) and jing will naturally arrive.

- Still your attempts to imagine and conceive of it.

- Relax your efforts to reflect on and control it.

- Be reverent and diligent and jing will naturally stabilize.

- Grasp it and don’t let go.

- Then the eyes and ears won’t overflow

- And hsin (the heart-mind) will have nothing else to seek.

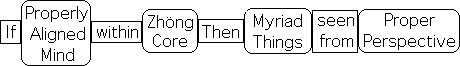

- When a properly aligned mind (cheng hsin) resides within you,

- The myriad things will be seen in their proper perspective.

The poem begins by stating that shên (spiritual energy) is naturally found within, but that it is elusive. Just like the Tao, jing and chi, it comes and goes somewhat unpredictably.

However we want it to remain, as it presumably leads to a well-ordered, i.e. balanced, life. Without shên, we are inevitably disorganized.

To better understand the interactions between the key concepts, let’s summarize the relationships from the last few verses. A well-ordered hsin leads to well-ordered speech and actions, which in turn lead to a well-ordered world (V10). Tranquility (ching) is a precondition for a well-ordered mind (V11). The disruption of our sense-desires repels shên (V12). Without shên, hsin is inevitably disordered (this verse). In brief, we need shên at our core if we are to have the well-ordered mind that exerts a positive effect upon the planet. (This logical sequence is yet another indication of the developmental nature of the Nei-yeh’s verses.)

Again the counsel is to ‘clean out the lodging place (shé)’ and jing (life force) will come naturally. Master Ni also spoke about the importance of emptying the Original Cavity in order to align with the Tao. He further stated that the Original Cavity is a physical location inside the middle of our brain.

![]()

Recall from Verse 8 that there are 3 conditions that must be fulfilled in order to create a lodging place (shé) for jing: 1) a stable mind, 2) eyes and ears acute and clear, 3) 4 limbs fixed. These conditions seem to suggest some kind of meditation, whether sitting or standing. Further 'eyes and ears acute and clear' suggests that we are in a state of readiness. While aware of our environment, we lack volition, in terms of fulfilling desires.

Shên seems to have jing energy associated with it (V1). If conditions are right, the energy pair emerges naturally. While we can move our arm or understand a concept, we can’t imagine or control this elevated condition. Instead, we must ‘diligently’ prepare a place and hope it comes.

We can’t imagine or control the synergy. However, if we are both reverent and diligent presumably in self-cultivation practices, specifically meditation, then we can stabilize the jing/shên synergy once it comes. Presumably, this superior form of internal energy won’t be so elusive. Instead shên will remain to properly order our life.

‘Reverence’ could have 2 components – respect for the importance of shên and proper humility. Humility is associated with emptying the mind’s Original Cavity of the thoughts and behavior associated with personal ego. If the mind is too full of the emotional thoughts associated with personal ego, the jing/shên synergy will be repelled. However, if we engage in regular ego cleansing, then we will be able to tap into this elevated energy source.

‘Diligence’ could also have 2 components – daily practice and regular attention. One Taoist text likens this concentrated attention to that of a setting hen. Once the hen begins setting, it doesn’t ‘forget’ the eggs for the 3 weeks or more that they take to hatch. Similarly, we must not forget our inner cultivation practices.

The final lines of song-poem #13 bring hsin, the heart-mind, into the process. Diligence in our practices stabilizes the jing/shên synergy. Then ‘the eyes and ears won’t overflow, and our mind (hsin) will have nothing else to seek’. Eyes and ears are frequently associated with desires. As Master Ni stated, we see something and want it. This statement also applies to hearing. We hear about something and we want it, even though we’ve never seen it. When disorganized, the powerful hsin focuses upon fulfilling the desires that are catalyzed by the eyes and ears.

Stabilizing the jing/shên synergy simultaneously aligns hsin, the innate processes of our heart-mind. With a properly aligned mind at our core, we are able to perceive our environment from the proper perspective, i.e. without the distortions of desires. With emotions balanced, we are more easily able to experience the direct nature of reality.

Hsin: our innate nature, not a cosmic energy source

With the inclusion of shên, the Nei-yeh has introduced all the cosmic energies. Let us speak a little about the unique relationship between hsin, our heart-mind, and te, will power. The ideogram for hsin appears 25 times in the Nei-yeh – more frequently that any other word-concept. Roth translates hsin simply as ‘mind’. This translation is good as long as we remember that hsin is different than our neurological brain and/or the Universal Mind of Buddhism.

Hsin is unique from the cosmic energies – jing, chi, shên united via the Way (Tao). These are all positive spirits that we want to attract and stabilize in our center (zhöng) because they bring vitality (shêng) and wisdom. They are abstract, unchangeable, universal power sources that are available to anyone at any time. However they are also elusive and somewhat unpredictable.

While the cosmic energies are general, hsin is individual and personal. Hsin can be viewed as our innate psycho-emotional nature. As such, we have inclinations and behavioral tendencies that can and should be modified and shaped, if we are to maximize our potentials.

While the rest of the energies are immutable, hsin goes through many transformations. These are the result of innate tendencies or processes. When hsin is well-ordered, our thoughts and behavior are balanced. When hsin is disordered or disrupted, our behavioral patterns are unbalanced.

Mind sees something and wants it. Automatic behavior patterns kick in to obtain the object of our desire. If we can’t fulfill our desires, we become angry. This anger generates inner turmoil that disrupts hsin, our heart-mind. This disruption repels the cosmic energies associated with the Tao. Without the Tao’s mental integration, our vitality (shêng) dims and our cognitive skills are compromised. This natural process is associated with hsin.

Generally speaking, mental turbulence repels the cosmic energies associated with the Tao, while mental tranquility (hsin ching) attracts them. In other words, our state of mind (hsin) is an exceptionally important ingredient in whether these universal energies remain or leave. While our mental state is somewhat unpredictable, one of the implicit messages of the Nei-yeh is that we don’t have to be a victim of the innate tendencies associated with hsin, our heart mind.

Te, our mental restraint muscle, can exert an effect upon these mental processes. If we view hsin as a wild horse, te is the mental muscle that we employ to rein him in and channel his energies. By exerting te, will power, we can enhance the likelihood of healthy processes and minimize the possibility of unhealthy behavioral patterns. Via te, we can restrict hsin’s natural tendencies that lead to the emotional disruption that drives away the cosmic energies.

Because the cosmic power sources are permanent, te has no effect upon them. However we can employ te, our will power, to mold hsin, or at least to encourage healthy processes and discourage unhealthy processes. By employing te to clean our inner spirit house of mental turbulence, we attract the jing/chi/shên synergy to our center.

Te is the mental muscle that we employ for inner cultivation, i.e. to calm the mind and align the body. In this sense, the Nei-yeh teaches us the best Way (the Tao) of employing te to cultivate body and mind (hsin) in order to both attract and stabilize the jing/ch’i/shên synergy. The self-cultivation process is designed to maximize both physical vitality and mental acuity.

Natural, i.e. effortless, for the Conservation of Mental Energy

The Nei-yeh frequently employs the ideogram for natural. From Verse 10, if mind is well-aligned, then our words and behavior naturally exert a positive effect upon those around us. Effortless is one of implications of natural behavior. If any action or process is natural, it takes the least amount of energy. In the quest to conserve or nurture our vitality (shêng), energy conservation is of prime importance. The Sage presumably spends his mental energy, his te, upon inner cultivation. Because of this focus, s(he) is able to move effortlessly – naturally. It is not necessary to spend any extra mental energy, as s(he) exerts a positive effect naturally. Minimizing energy expenditure maximizes vitality.

The important Chinese word-concept, wu-wei (non-action in the midst of action) reflects this effortless movement. In the internal martial arts, the master’s goal is to employ the opponent’s energy rather than his own. However, the master is only able to move ‘naturally/effortlessly’ after decades of training. The same condition holds on the political level. After decades of inner cultivation, the Sage’s impeccable social behavior naturally exerts a positive effect upon the world.

Perhaps influenced by or at least partaking of the same tradition, the Chuang Tzu reflects and extends this theme: personal alignment must precede political action; else the action is corrupt. If the individual is unbalanced, presumably his/her thoughts and actions are also unbalanced. This internal imbalance further imbalances the surrounding world. As an example, it is best not to speak when angry, as regrettable words will be spoken, which in turn lead to regrettable consequences.

Summary: Verses 10>13

Let us summarize to reinforce retention.

V10) A well-ordered mind naturally generates a well-ordered human world due to balanced thoughts and actions.

V11) Mental tranquility is a prerequisite for a well-ordered mind. Aligning our body strengthens te, our will power.

V12) Shên generates intuitive understanding. Over-stimulated senses disrupt hsin, which drives away shên.

V13) Shên’s intuitive understanding is required for the well-ordered mind that generates a well-ordered world. Shên is only present with jing at our center. To attract and stabilize jing, we must clean out shé, our internal spirit house, via regular meditation practices (V8). A stabilized jing limits desires, which leads to mental alignment and subsequently to the well-ordered mind that harmonizes the world.

Footnotes

1 Harold Roth, Original Tao, Inward Training (Nei-yeh), Columbia University Press, 1999, p. 70. Each translation of the Nei-yeh's verses comes from this book.

2 The Great Learning translated by A. Charles Muller, 7-4-2013, http://www.acmuller.net/con-dao/greatlearning.html

3 Concise English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 395

4 Concise English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary, p. 234

5 Barbara Aria & Russell Eng Gon, The Spirit of the Chinese Character, p.16

6 Chinese Characters, Dr. L. Wieger, original 1915, 1965, p. 138

7 Chinese Characters, Dr. L. Wieger, original 1915, 1965, p. 138

8 The dictionary shows zhong with a flat line over the 'o'. Due to the limitations of my keyboard, I employ the umlaut to represent the straight line.

9 Chinese Characters, Dr. L. Wieger, S. J. Dover Publications, Inc., New York, translated into the English by L. Davrout, S. J., 1965, 1st published 1915, p. 260

10 Chinese Characters, p. 260