4. Nei-yeh 7>9: Cosmic Relationships

- Verse 7. Heaven, Earth, & Humans: Ruling Principles and Processes

- Verse 8. Aligned Body & Tranquil Mind attracts Jing, the essence of Ch'i.

- Guiding Ch'i = Tao-yin

- Jing’s Definitions & Ideogram

- Verse 9. Holding Fast to the One

- Master Ni on 'the One'

Introduction

Verse 7. Heaven, Earth, & Humans: Ruling Principles and Processes

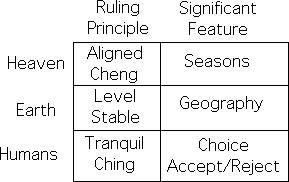

Verse 7. Ruling Principles & Processes of Heaven (cheng, seasons), Earth (stable, geography), Humans (ching, choice)

- For Heaven1, the ruling principle is to be aligned (cheng).

- For Earth, the ruling principle is to be level.

- For human beings, the ruling principle is to be tranquil (ching).

- Spring, autumn, winter and summer are the seasons of Heaven.

- Mountains, hills, rivers and valleys are the resources of Earth.

- Pleasure and danger, accepting or rejecting are the devices of human beings.

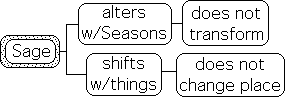

- Therefore the Sage (sheng):

- Alters with the seasons, but does not transform,

- Shifts with things, but does not change places with them.2

Verse 7 introduces an important traditional Chinese metaphor. It consists of a trio of concepts: Heaven (tian), Earth (di), and Humans (ren). As an indication of its significance, the hexagrams of the I Ching are divided into 3 parts that correspond with this division.

This song-poem delineates the ruling principle behind each of these principles/processes: Heaven aligned (cheng); Earth level; and Humans tranquil (ching). Further Heaven consists of seasons; Earth has its geography; and Humans have anger and pleasure (emotions) that they can accept or reject. We take these lines to indicate that humans have the ability to choose, in this case whether or not to cultivate emotional tranquility.

The verse ends by stating that the Sage is able to flow along with the seasons without being transformed by them. He shifts but does not change place.

What does this mean?

The text identifies the characteristics of Heaven, Earth and Humans that distinguishes them from each other. While Heaven and Earth go through seasonal transformations and topographical/material variations, as is their nature, the Sage adapts to them. By adapting, he avoids the emotions of the non-sage, and thus maintains the constancy of the tranquil Tao in his heart-mind, the essence of his humanity. Alignment and balance are acquired as a result of his tranquility.

Verse 8. Aligned Body & Tranquil Mind attracts Jing, the essence of Ch'i

Verse 8. Cheng, Ching & Stability create space (shé) for jing, the essence of ch’i. ‘Guiding ch’i’ generates jing, which leads to thoughts and then knowledge. Excess knowledge harms vitality (shêng).

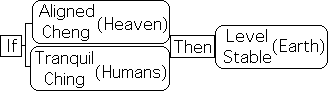

- If you can be aligned (cheng) and be tranquil (ching),

- Only then can you be stable.

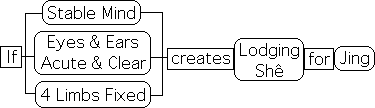

- With a stable mind (hsin) at your core (zhöng),

- With the eyes and ears acute and clear,

- And with the 4 limbs fixed,

- You can thereby make a lodging place (shé) for the vital essence (jing).

- The vital essence (jing); it is the essence of vital energy (ch'i).

- When the vital energy (ch'i) is guided, it [jing] is generated (shêng = vitality).

- When it (shêng) is generated, there is thought.

- When there is thought, there is knowledge.

- But when there is knowledge, then you must stop.

- Whenever the forms of the mind (hsin) have excessive knowledge,

- You lose your vitality (shêng).

Verse 8 integrates many of the notions introduced in the preceding verses. Only by being aligned (cheng) and tranquil (ching) can hsin, our heart-mind, become stable. This statement evokes the ruling principles of the triad of processes (Heaven, Humans and Earth) from the preceding verse.

If our 4 limbs are aligned (like Heaven), our sense-desires are tranquil (like the ideal Human), and our mind (hsin) stable (like Earth), this condition creates a lodging place (shé) for jing, the generative energy.

This is the first verse that makes an apparent reference to sitting meditation. The 'four limbs fixed' sets the context for a stable mind and clear/acute senses, i.e. eyes and ears. Roth reads the verse and entire Nei-yeh as an ancient meditation manual.

However, the word that Roth translates as ‘fixed’ could also be translated as ‘firm’. In this case, the verse could be referring to a synergistic complex of physical practices that might include quietude. In contrast to most forms of meditation, the senses, i.e. eyes and ears, are still engaged, not denied. Rather than motivating desires, they seem to be in a quiescent state of observation.

The text is beginning to answer the unspoken question from Verse 1. How do we get jing to reside in the center (zhöng) our chest, i.e. hsin, our heart-mind, so that we can become a Sage? The practice of meditation cultivates both an aligned (cheng) body and tranquil (ching) mind. This process creates an attractive internal spirit house (shê) that invites jing (life force) into hsin – our heart-mind.

As an indication of Taoism’s continuity (its ‘enduring tradition’), the practice of dual cultivation of body and mind remains an identifying and significant feature of Ch’uan-chen Taoism, one of Taoism’s 2 significant branches. Originating in the modern period and maturing during the Yuan Dynasty, the Ch’uan-chen tradition persists into 21st century, over 2 millennia after the Nei-yeh was composed. Ch’uan-chen Taoism considers itself to be part of an unbroken chain with Inner Alchemy. Due to the congruence of its teachings and concepts with this ancient system of inner cultivation, the Nei-yeh could be considered a significant text, perhaps the earliest, in the alchemical tradition.

Line 7 identifies the relationship between the powerful jing and ch’i energies. Jing is the essence of ch’i. Traditionally, both ch’i and jing3 have universal and individual aspects - macrocosm and microcosm. On the individual level, jing is associated with sexual energy, while ch’i with breath. On the universal, jing animates life and spirits, while ch’i animates the cosmos.

![]()

Line 8: Guiding ch’i generates shéng (vitality). Roth suggests that this vitality is associated with jing. Recall from Verse 2 that ‘developing te’, our inner power, is required to stabilize the elusive ch’i energy. Could te be the mental muscle that allows us to guide ch’i with its resultant jing energy? If so, what is this te that we should be developing? We suggest self-restraint/will power.

The remaining lines of the song-poem warn us of the dangers of the jing-ch’i process. Jing generates thoughts, which generate knowledge.

![]()

But excess knowledge harms our vitality (shêng). We must moderate, even halt, this process – this generation of knowledge – in order to protect our vitality (shêng).

![]()

How do we halt this process? Could te, our inner will power, be the key?

Guiding Ch'i = Tao-yin

Line 8 suggests that 'guiding ch'i' leads to vitality (shêng); alternately 'generates jing (life force)'. It is evident that the Nei-yeh considers 'guiding ch'i' to be a significant method of enhancing personal energy. What does it mean to 'guide ch'i'?

Roth's footnote associated with the translation of this line provides some insights into the possible meaning.

"53. Riegel would emend tao to t'ung because of similar form corruption. While this is possible, I think that Chao Shoui-cheng's emendation better suits the semantic context here. His suggestion of tao is the tao of the tao-yin, the guiding and pulling exercises to circulate the vital breath (ch'i) that are referred to in both the Chuang Tzu 15 and Huiai-nan 7 and in texts excavated from Ma-wang-tui and Chang-chia-shan. While I do not think that these physical exercises are being suggested here, I do think that the guiding of the vital breath (ch'i) while seated is what this line, and the entire verse is talking about."4

According to Roth's understanding, 'guiding ch'i' is associated with 'tao-yin', i.e. physical practices that consist of 'guiding and pulling exercises to circulate the vital breath (ch'i)'. A number of significant traditional Taoist texts refer to these physical practices. Due to the reference to ‘4 limbs fixed’ in line 5, Roth suggests that this particular verse is referring to the breath regulation that occurs in stationary meditation, whether sitting or standing.

As mentioned, rather than ‘fixed’, the 4 limbs could be ‘firm’. Under this interpretation, the verse could be referring to controlling the breath while performing deliberate physical exercises, perhaps proto-Tai Chi. While practicing Tai Chi, we must concentrate on integrating our breath with the movement of our legs and arms, which are flexible, firm and light. Indeed the expression ‘iron in silk’ reflects this relationship.

Whether sitting or active, guiding ch'i seems to include intentionality. On the particular level, it is essential to consciously move ch'i, i.e. the breath, around our respiratory system while meditating. In a larger context, consciously guiding this cosmic energy source throughout our body evokes personal vitality.

It is not enough to behave or move automatically. Inadvertently going through the motions is insufficient. To get the added benefit, we must intentionally move ch'i through our bodily channels, from our fingertips to toes. The Nei-yeh continues this theme in later verses.

Verse 9. Holding Fast to the One

Verse 9. Hold fast to the One to change things without both being changed and losing ch’i.

- Those who can transform a single thing, call them 'numinous' (shên).

- Those that can alter even a single situation, call them 'wise'.

- But to transform without expending vital energy (ch'i); to alter without expending wisdom:

- Only exemplary persons who hold fast to the One are able to do this.

- Hold fast to the One, do not lose it,

- And you will be able to master the myriad things.

- Exemplary persons act upon things,

- And are not acted upon by them,

- Because they grasp the guiding principle of the One.

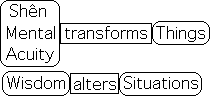

Verse 9 introduces a new concept, simply ‘the One’. It takes shên to ‘transform things’ and wisdom to ‘alter situations’. Roth translates shên as ‘numinous’, a decidedly ambiguous term – a placeholder with little relevance to the contemporary reader. The following diagram associates shên with spirit. This is a common association, but somewhat misleading. Suffice it to say for now that shên is linked to our cognitive powers.We will explore the nuances of this important word-concept in more depth in subsequent verses of the Nei-yeh.

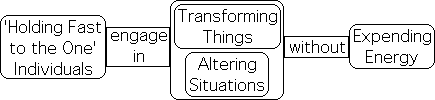

But only individuals who ‘hold fast to the One’ are able achieve these changes without losing ch’i or expending wisdom. Only by grasping the ‘guiding principle of the One’ are they able to act upon things without being changed.

Roth equates the One with the Tao. This works well in the song-poem. By holding fast to the ‘guiding principle’ of the Tao, we can transform the world without being changed or losing our ch’i. However, the Tao is quite ambiguous, as we’ve seen. What are the specifics of ‘holding fast to the One’?

Master Ni on 'the One'

Tao is frequently employed to mean the ideal way, path or method. Which is the ideal method – the ‘guiding principle’ – that enables us to act without losing energy? Master Ni offers some insights in this regard.

Master Ni: One = Taiji = Balance point between yin & yang = Two

Although the Tao and the One are related, Master Ni offers some refinements.

Ni: “From Wuji comes Taiji. (He draws a circle with his finger and dots the center.)

From Nothing comes the One, which splits Wuji into Yin and Yang.

Although Two Hands, Yin and Yang, Substantial and Insubstantial,

They move as One, Taiji, always circling, like Wuji.

No edges.” (February 16, 2000)5

This quotation suggests that the One is taiji, the balance point between yin and yang, the Two. Further the One emerges from Zero, wuji. In this context, ‘holding fast to the One’ means to maintain the balance, taiji. Residing in the middle, we swing like a door, but are not changed. This interpretation of the One removes some of the Tao’s mysticism and replaces it with a pragmatic suggestion: Hold to the middle.

Master Ni: ‘Join Mind as One’ = ‘Return to the One’

How do we ‘hold to the middle’? Master Ni provides some suggestions in this regard.

Ni: “Tai Chi is balance of Yin & Yang.

Humans a balance of yin and yang.

If 50-50, healthy. If not, then sick.

Tai Chi 2 - Martial 3 - Tao 1.

How to ‘Return to the One’?

Join Mind as One - this is Tao.

This is ‘Return to the One’.

Tai Chi can go Martial or Tao.

I teach Tao.”

In this statement, Master Ni equates ‘Joining the Mind as One’ with ‘Returning to the One’. Further he equates this process with the Tao, as the ideal method or algorithm for living. According to traditional Taoist philosophy, we are born integrated. Living in this world fragments this initial integration. One of the goals of self-cultivation practices is to return to our original state, the One.

This is accomplished by ‘Joining the Mind as One’. This implies that the Mind has multiple parts that might act independently of one another – implying a lack of integration.

How do we ‘Join Mind as One’?

Ni: “Mind very powerful. Sees and wants. Must eliminate desire.

Unite jing, ch’i, shên as One.

Then blend lights, internal and external, with integrated energy.

This is the Way.”

Like the Nei-yeh, Master Ni considers hsin, our heart-mind, to be the source of desire. This quotation indicates that Mind consists of the classic trio of energies – jing, ch’i, and shên. We must unite these energies and then blend this ‘integrated energy’ with the lights from our eyes in order to ‘Join the Mind as One’. This is the Way, the Tao, of eliminating desires. (We are familiar with the cosmic energies jing and ch’i; shên’s introduction is coming soon.)

Master Ni finishes with this line. ‘This is the Way, [the Tao]’. Instead of being the One, the Tao is equated with the method of integrating the Mind. ‘Joining the Mind as One’ is the process of the Tao. The Tao is neither the One, nor the Mind, but represents the method of integrating the Mind as One to eliminate desires.

In this context, ‘Returning to the One’ means returning to the original state, when the Mind was integrated and balanced. The Tao is the Way, i.e. the method of eliminating desires via mental integration.

Verses 7 >9: Summary

Summarizing verses 7 >9 to aid retention:

V7) The ruling principles of Heaven, Earth and Humans are alignment (cheng), balance, and tranquility (ching). Heaven has seasons; Earth its geography; and Humans have choice.

V8) This verse examines the nature of jing in greater depth than prior verses. By following the ruling principles, we create an internal space (shé) for jing, the essence of ch’i. Another interpretation could be that the meditation process attracts jing into hsin, our heart-mind. ‘Guiding ch’i’ generates vitality (shêng) or alternately, life force (jing). This significant process generates thoughts and knowledge, which must be moderated to avoid harming vitality. These are powerful concepts.

V9) We must ‘hold fast to the One’ to change the world without both being changed and/or losing ch’i. The One could be the Tao, the method of self-cultivation, or it could be the integrated mind that is the result of uniting jing, ch’i, and shên. Perhaps a united psyche is both resistant to change due to crowd pressures and less likely to over-use jing-ch’i energy, thereby depleting vitality (shêng).

Footnotes

1 In order to avoid confusion with Biblical Heaven, Roth translates the ideogram for tian as 'the heavens'. We prefer simply 'Heaven'. This translation provides more clarity due to the context of this work. The ideogram 'tian' is employed in the well know Chinese idiom 'Mandate of Heaven'. Further, this work has traced the development of the concept of the Shang sky god to Chinese Heaven. For these reasons, we will employ the word 'Heaven' as the translation for tian.

2 Harold Roth, Original Tao, Inward Training (Nei-yeh), Columbia University Press, 1999, p. 46. Each translation of the Nei-yeh's verses comes from this book. I include the Chinese words for elucidation.

3 Note: For clarity, I am deliberately mixing two different romanization systems: Wade Giles ch’i, ching, Dao; Pinyin qi, jing, Tao.

4 Roth, p. 221

5Master Ni’s Principles for Tai Chi & Life, don lehman jr., Lulu Press, 2015, p. 25. All of the Master Ni quotes come from this book.